Another common method for zoning hydronic heating and cooling systems is based on a single circulator combined with an electrically operated zone valve in each circuit. A thermostat in each zone signals its associated zone valve to open when heating (or cooling) is needed. In most systems, the circulator and the heat source (or the chiller) are also enabled to operate whenever one or more zones are calling for heating or cooling.

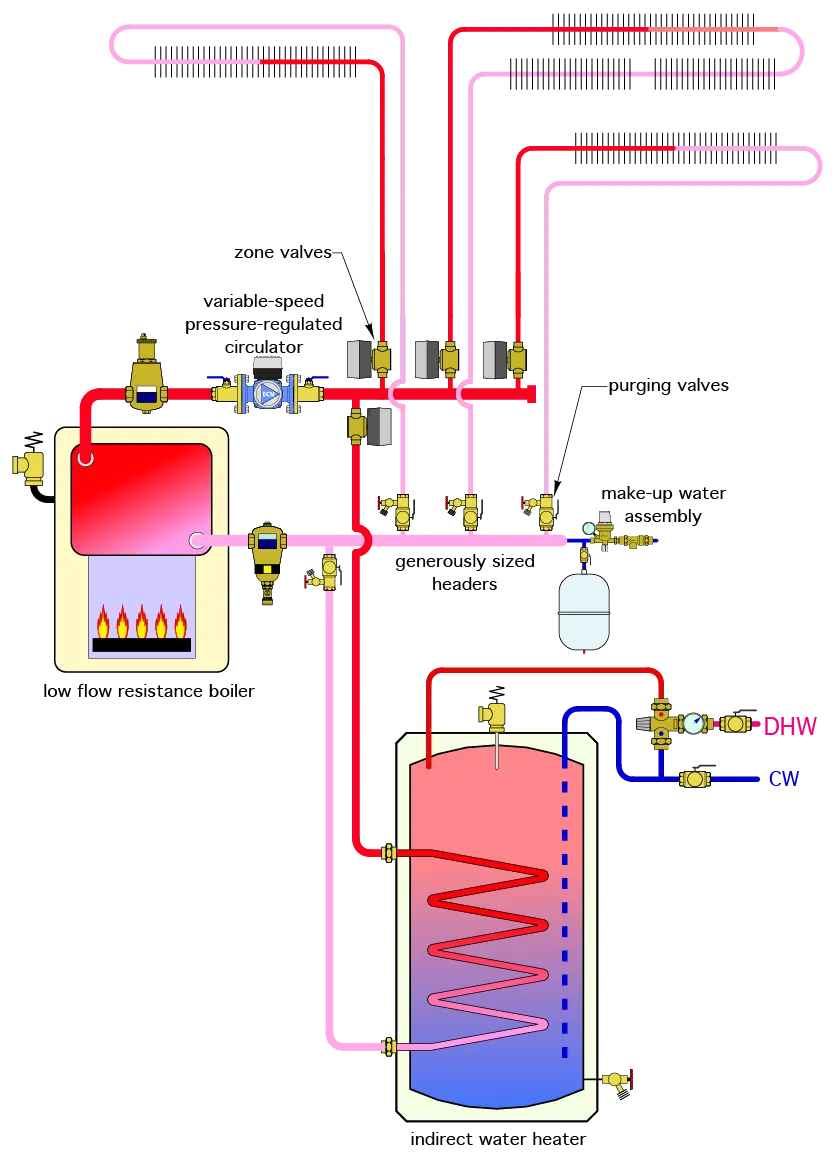

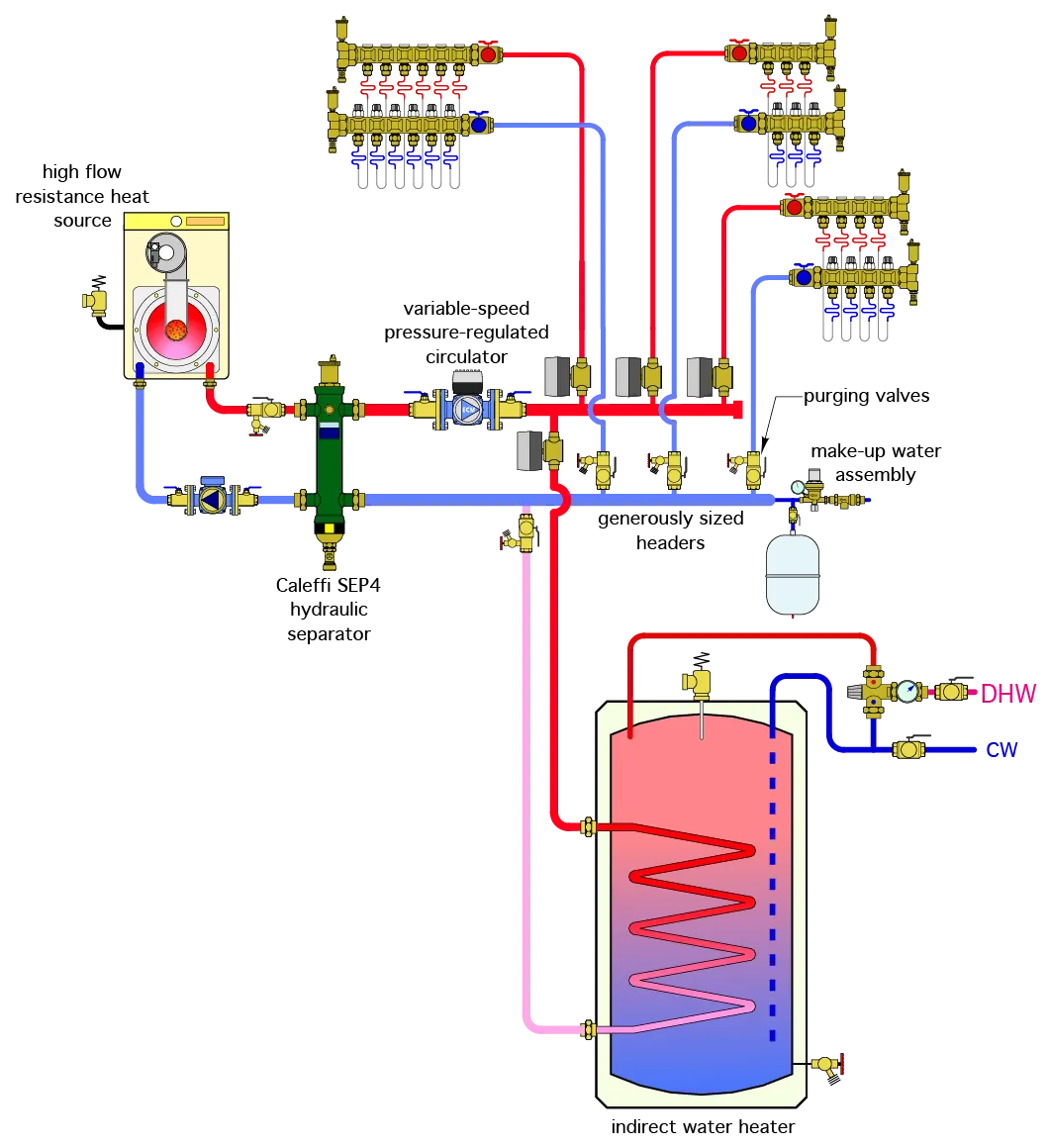

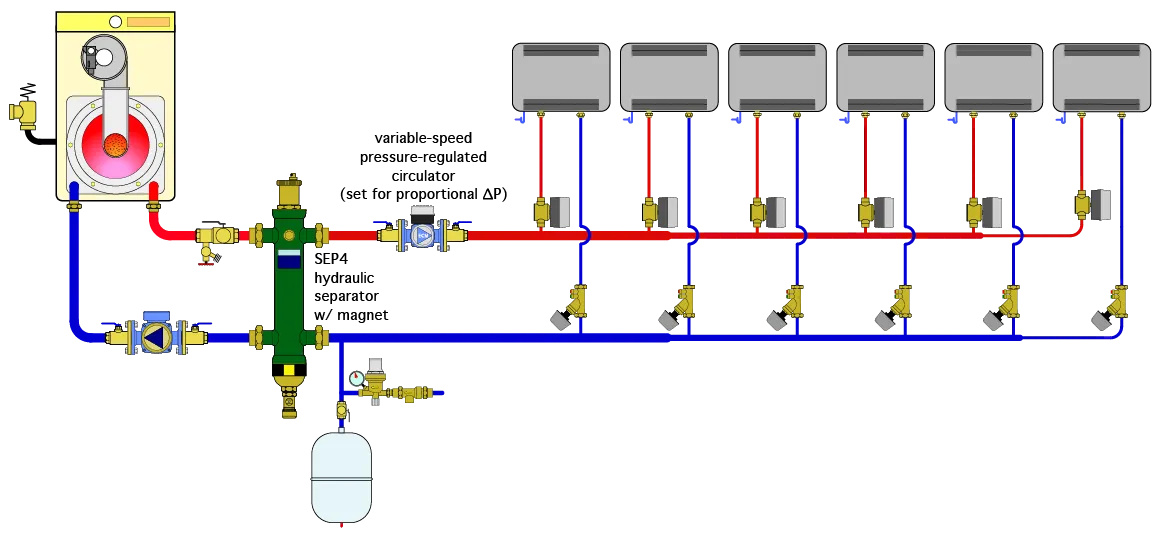

Figures 3-1a and 3-1b shows two common piping arrangements for a four-zone heating system.

Each of these systems uses a single variable-speed pressure-regulated circulator to create flow through any active zone circuit(s).

The system in figure 3-1a is based on a low-flow-resistance heat source, such as a cast iron boiler. The headers connect directly to this heat source.

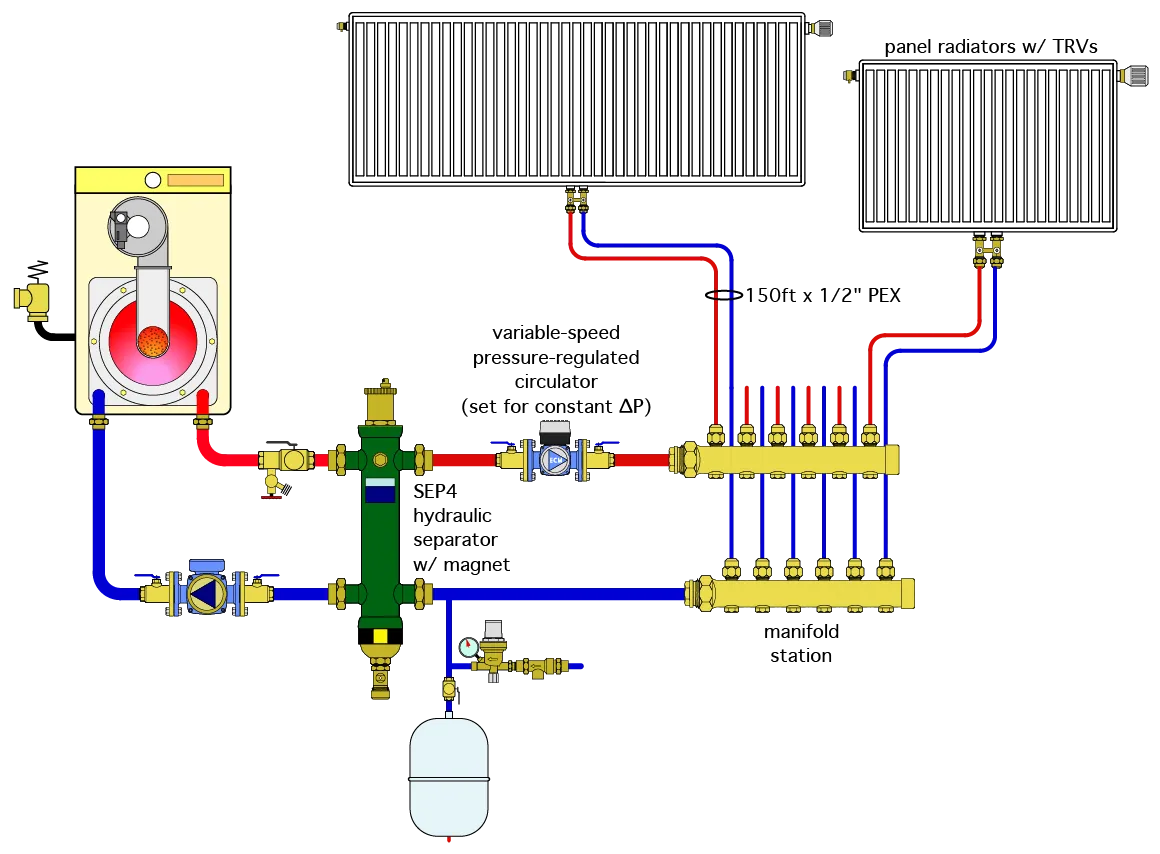

The system in figure 3-1b is based on a high-flow-resistance heat source, such as certain modulating/condensing boilers or a hydronic heat pump. Due to its high flow resistance, the heat source has its own circulator. The headers connect to a Caleffi SEP4 hydraulic separator, which prevents undesirable interaction (e.g., hydraulic separation) between the boiler circulator and the variable-speed distribution circulator.

There are many similarities between figure 3-1a, b and figure 2-1a, b. All four piping configurations provide purging valves on the return side of each zone circuit. All of them have components that provide air, dirt and magnetic particle separation. All of them use short and generously sized headers.

One advantage of valve-based zoning is that it only requires a single circulator. When properly sized, selected and configured, that circulator can operate on lower input power relative to a similar system using zone circulators. This was demonstrated in the previous section by calculating and comparing the distribution efficiency of a system with zone valves versus an equivalent system with electrically operated zone valves.

Many modern circulators have variable-speed pressure- regulated circulators with electronically commutated motors (ECM). These circulators are ideal for systems using zone valves. They can be set to automatically vary their motor speed based on changes in operating conditions as zones valves open and close. Under partial load conditions, which are present most of the time in a typical heating season, these circulators can operate at reduced input power, resulting in substantial energy cost savings relative to fixed-speed circulators.

Valve-based zoning is well suited to circuits that need to operate at low flow rates. Examples include circuits serving individual panel radiators or fan coils. In some cases, these heat emitters only require flow rates in the range of 0.5 to 2 gallons per minute. Zone circulators may not have motor speed adjustments low enough to meet these flow rates. In that case, some type of balancing valve would be required to throttle the flow. This approach, while possible, is not as energy efficient as valve-based zoning combined with a variable-speed pressure-regulated circulator.

When properly selected, motorized zone valves provide much higher resistance to unintentional forward differential pressure compared to the nominal 0.5 psi forward opening resistance of a typical spring-loaded check valve in a zone circulator. This unintentional forward differential pressure can be caused by poor system design, such as the lack of hydraulic separation between circulators. The ability to resist forward differential pressure is based on the zone valve's close-off pressure rating, which is discussed later in this section.

Another advantage is that most zone valves operate on low voltage (24 VAC). Most codes do not require this low-voltage wiring to be installed in conduit or by a licensed electrician.

One disadvantage of zoning with valves is that the failure of the circulator would prevent flow in all zones. Although possible, modern circulators, when properly selected and installed, have an excellent record for reliable operation over many years.

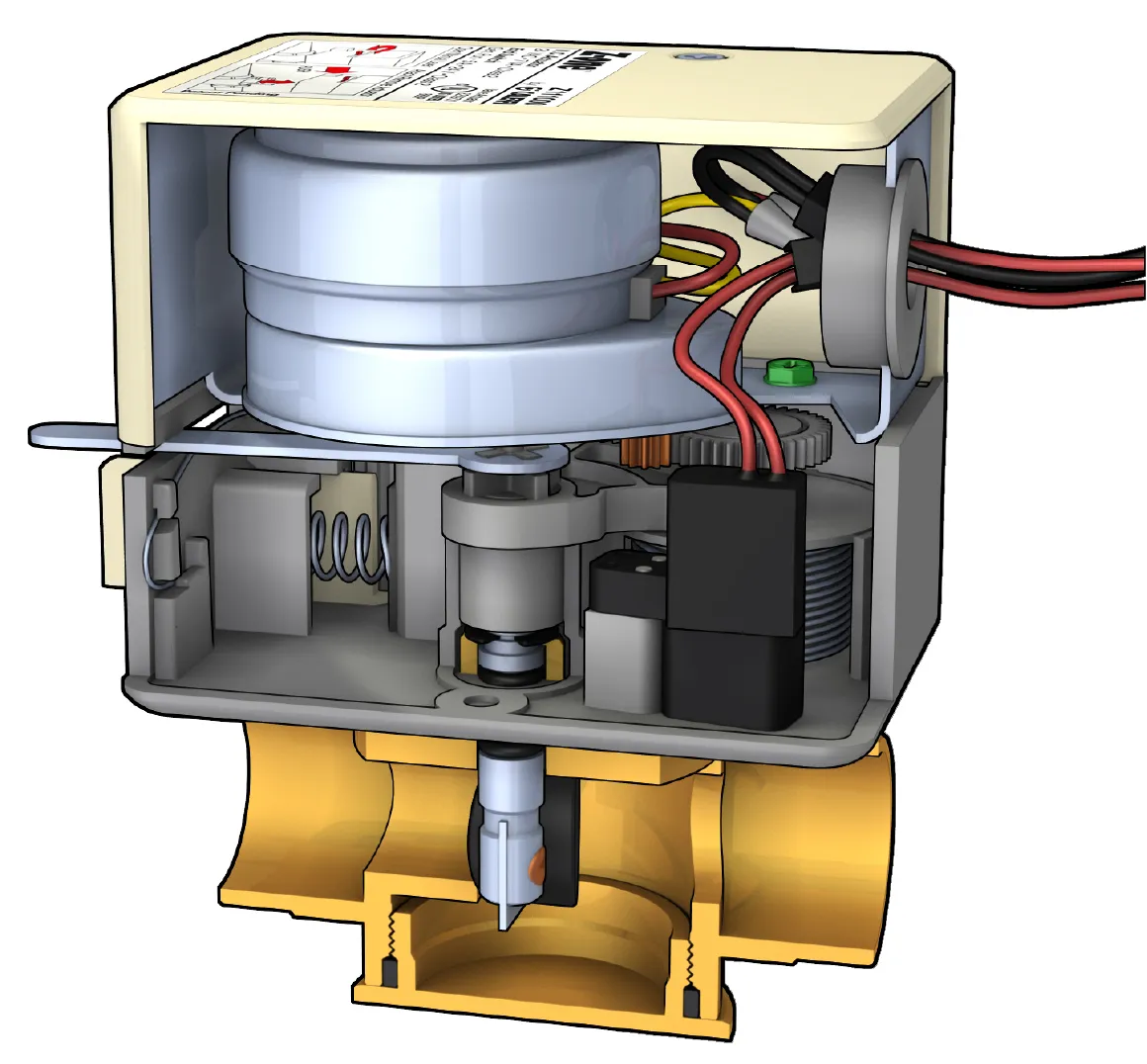

The most common type of electric zone valve uses an actuator in which a small AC motor turns a gear assembly that rotates the valve's shaft. That rotation moves a paddle away from the valve's seat, allowing flow through the valve. As the valve opens, a spring assembly inside the actuator is wound under tension. When the paddle reaches its fully open position, the motor stops, and a very low electrical power input holds the motor in that position. When power is removed, the spring assembly unwinds, rotating the shaft backward to close the paddle against the valve's seat. This spring also creates the force that opposes the pressure created by the system's circulator, keeping the unpowered valve closed while other zones are operating.

Figure 3-2 shows two cut-away illustrations of the Caleffi Z-one™ zone valve. Figure 3-2a shows the actuator mounted to the brass valve body. The motor/gear assembly is seen at the top of the actuator. The shaft and paddle are seen inside the valve body.

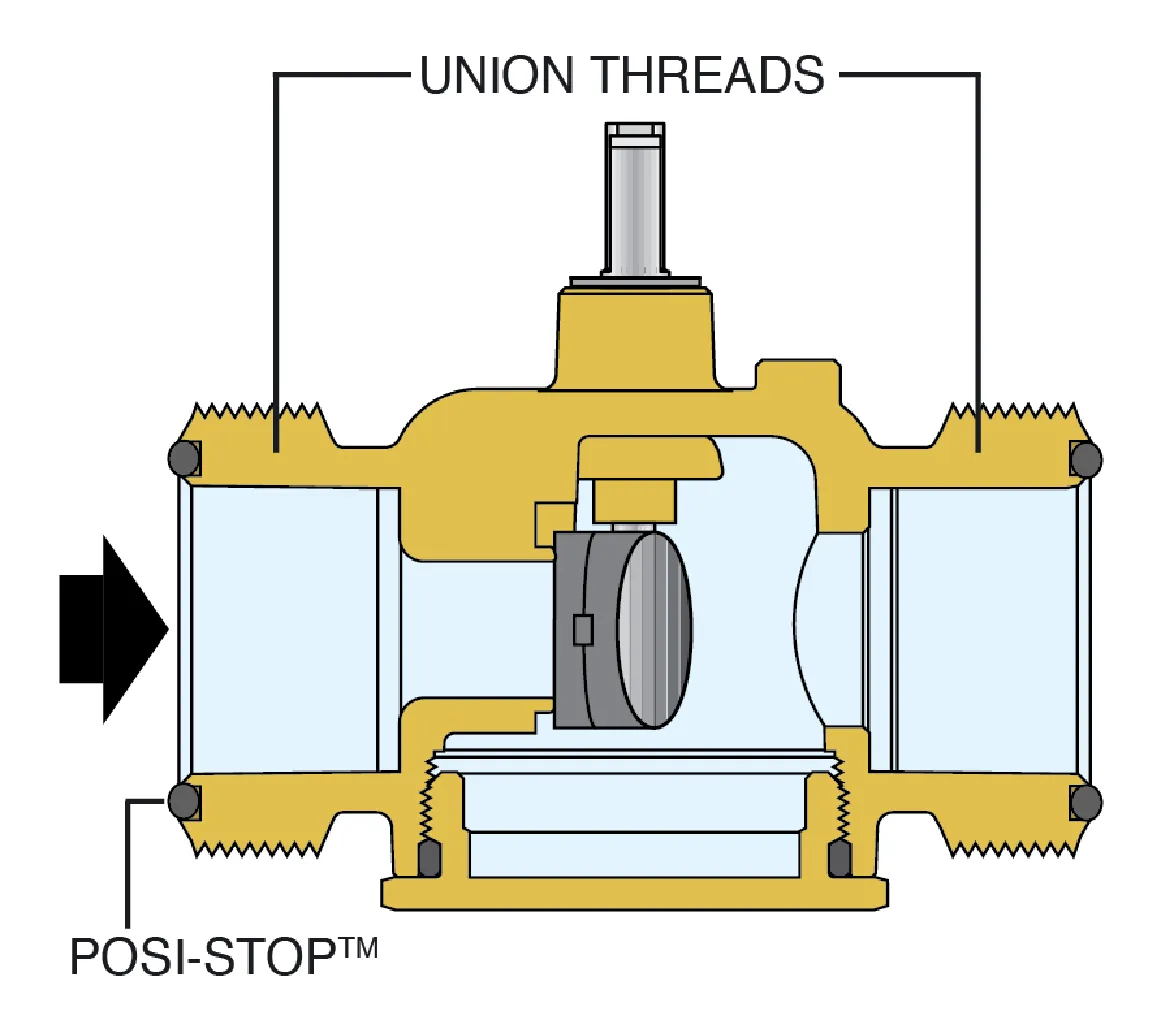

Figure 3-2b shows the currently shipping version of this valve with Posi-Stop™ connections on both valve ports. Posi-Stop connections allow the valve body to be fitted with several tailpieces that connect to soldered copper tubing, NPT threaded fittings, press fittings or PEX compression fittings. An embedded O-ring provides the pressure-tight seal between these tailpieces and the valve body.

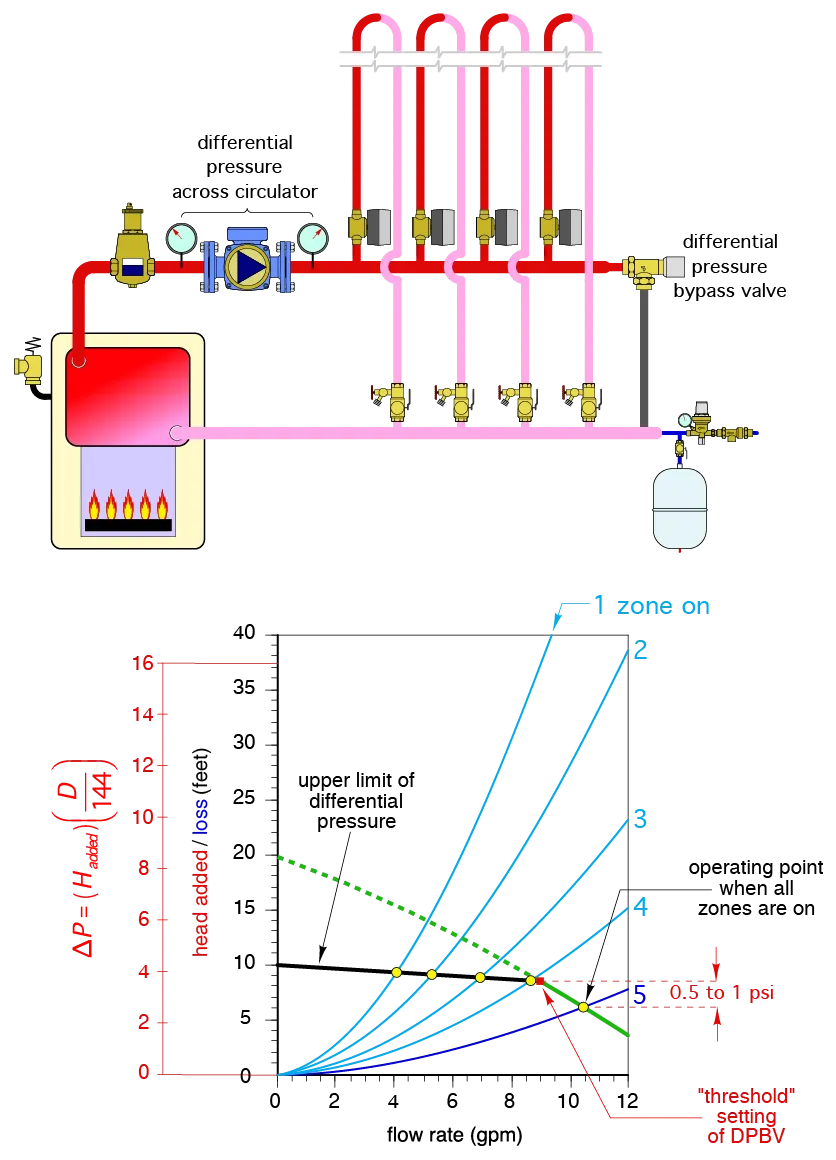

The operating condition of the circulator in a system with zone differential pressure across circulator differential pressure bypass valve valves can vary widely, depending on how many zone circuits are present and how many zones are active.

Consider the simple four-zone system shown in figure 3-3. Assume that this system has a fixed- speed circulator. The pump curve for that circulator is shown (in red) in the graph below the piping schematic.

When all four zone valves are open, the flow resistance of the distribution system as a whole is relatively low and is represented by the dark blue curve. This curve crosses over the red pump curve at a point. that corresponds to a flow rate of approximately nine gpm. This is the flow rate through the circulator under this condition.

When one of the zone valves closes, the head loss of the distribution system as a whole increases, as represented by the light blue curve labelled "3 zones on" in figure 3-3.

The intersection between this curve and the circulator's pump curve has moved to the left and to the previous condition when all four zones are operating. The movement to the left implies that the flow rate through the circulator has decreased. The upward movement indicates that the head at which the circulator operates has increased, which also implies that the differential pressure across the circulator has increased. That higher differential pressure is exerted on the three active zones. This causes an increase in flow rate through each active zone.

A similar response occurs when another zone valve closes, as represented by the light blue curve labelled "2 zone on" in figure 3-4. The differential pressure across the circulator increases more, and so does the flow rate in each of the two active zones.

When only one zone is active, the differential pressure across the circulator is even higher. These increases in differential pressure as zone valves close can lead to problems, including:

• Increased flow noise in the active zone circuits due to high flow velocity.

• Potential erosion of the metal in pipe or valves due to high flow velocity.

• The possibility that the spring within any inactive zone valve cannot hold the valve's paddle fully closed, and thus, allows some flow through zones that are supposed to be off.

• Potential cavitation of the circulator depending upon system static pressure, water temperature and the location of the expansion tank relative to the circulator.

In an ideal system, there would be no change in differential pressure across the circulator as the number of active zone circuits changes. Systems using a fixed-speed circulator can be designed to "approach" this ideal condition. Systems using a properly set variable- speed pressure-regulated circulator can achieve this ideal condition.

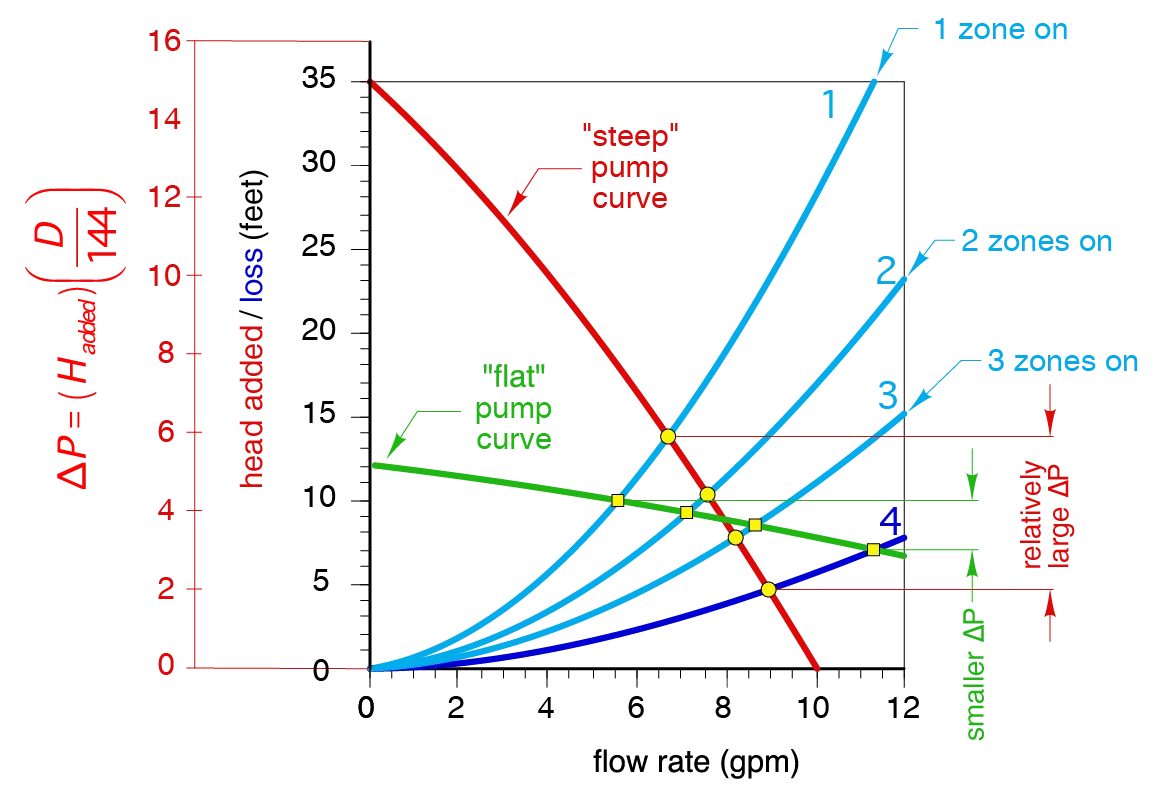

One way to limit the undesirable increases in differential pressure as zone circuits turn off is to select a fixed- speed circulator with a relatively "flat" pump curve, as shown in figure 3-3.

Although the operating points still climb upward as zone valves close, the vertical shift is much less for the circulator with the "flatter" (green) pump curve compared to the shift experienced with the previous circulator with the (red) pump curve. This demonstrates that fixed-speed circulators with flatter pump curves are better suited for systems using zone valves. Fixed-speed circulators with "steep" pump curves should not be used in systems with zone valves.

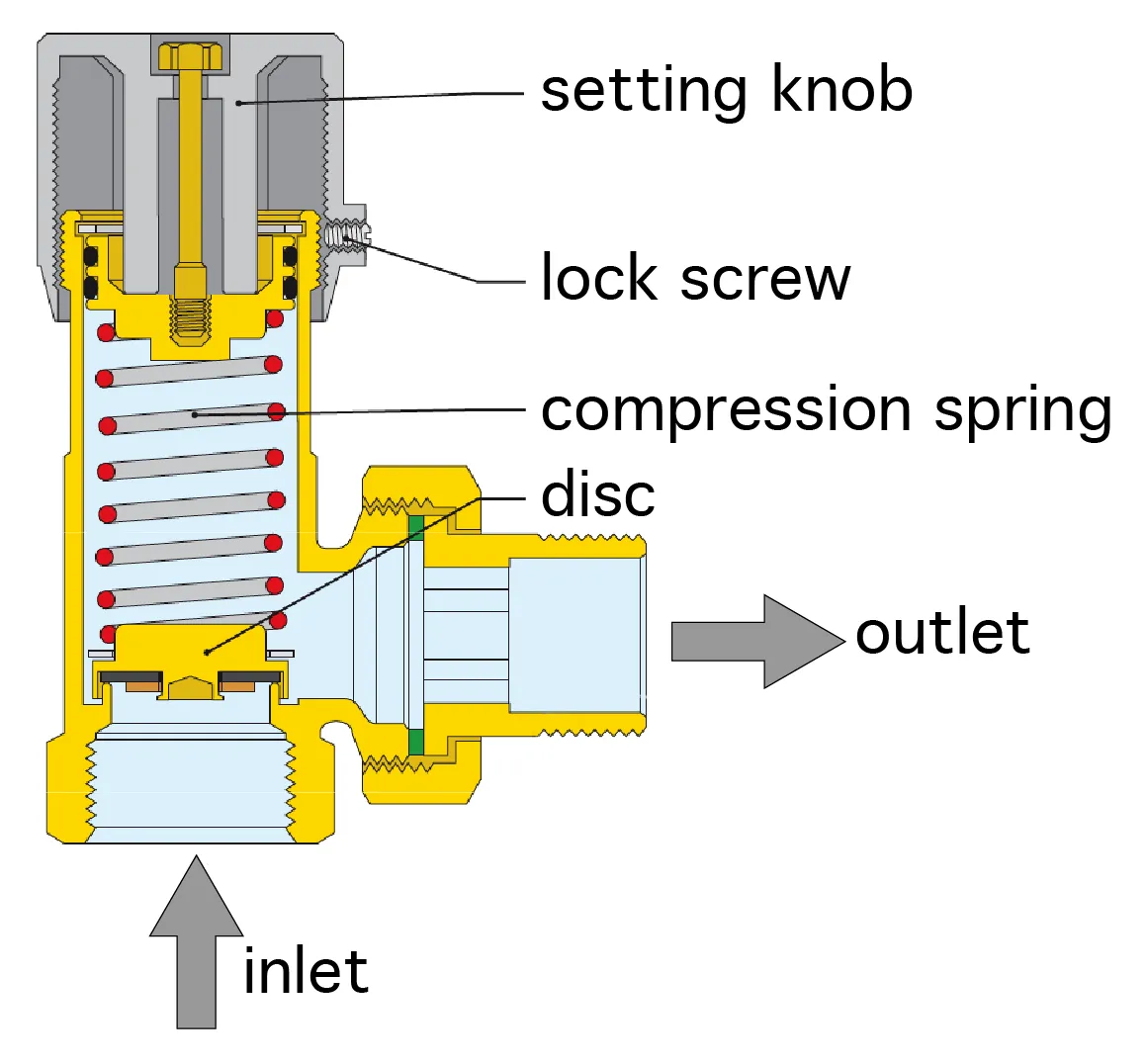

Another way to limit differential pressure increase in systems using zone valves and a fixed-speed circulator is to install a differential pressure bypass valve (DPBV). An example of such a valve, along with its cross section is shown in figure 3-5.

A differential pressure bypass valve has a disc that’s held against the valve’s seat by a spring. The knob adjusts the force exerted by the spring on the disc. This force, in combination with the diameter of the disc, determines the differential pressure at which the disc begins to move away from the seat. This pressure is called the “threshold” pressure setting. If conditions in the system attempt to further increase the differential pressure across the valve, the disc begins moving away from the seat. This allows increased flow through the valve, while maintaining minimal variation in the differential pressure between its inlet and outlet ports.

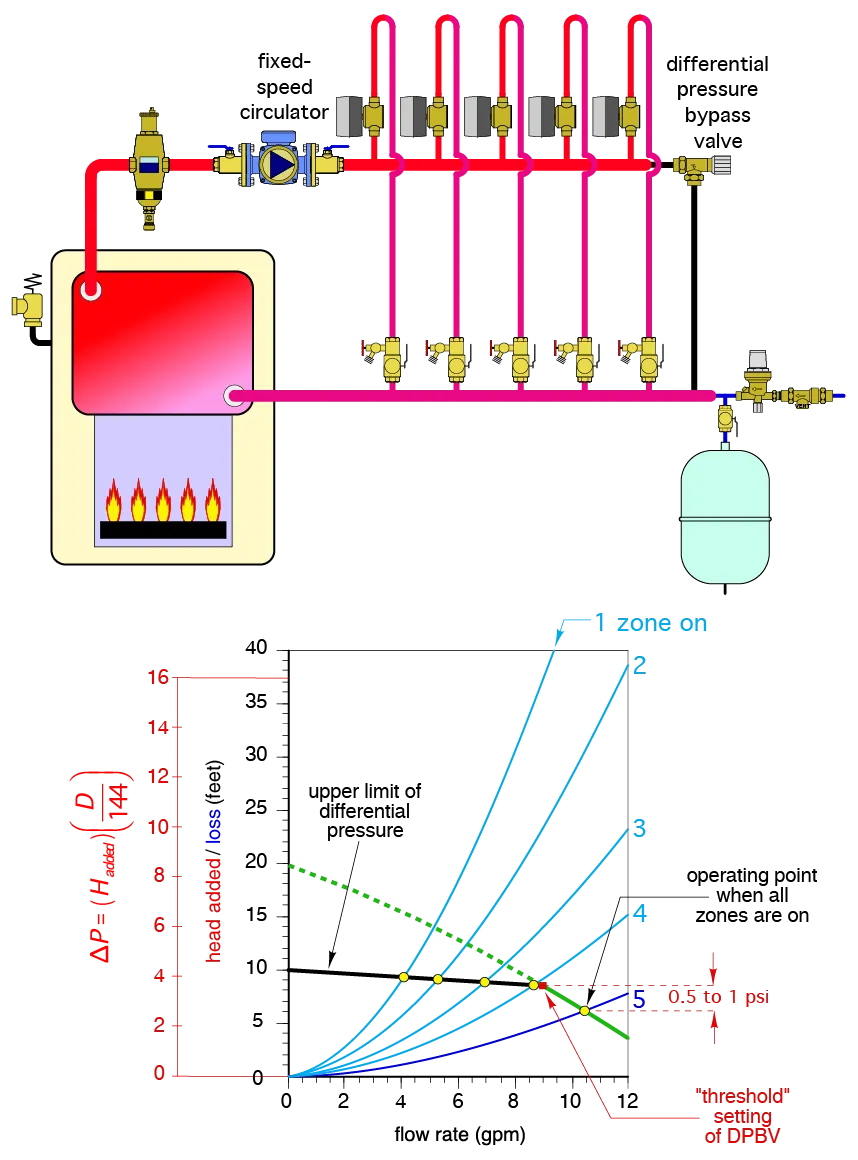

An example of a five-zone system with a fixed-speed circulator and a DPBV installed across the headers is shown in figure 3-6.

The dark blue head loss curve represents a condition in which all five zone circuits are operating. Under this condition, the differential pressure exerted on the DPBV is below its threshold setting. Under this condition, the DPBV remains fully closed and has no effect on the system.

As the number of active zone circuits decreases, represented by the "steeper" light blue curves, the differential pressure across the circulator and across the headers attempts to increase.

For the setting represented in figure 3-6, the DPBV begins to open when the differential pressure across it reaches 0.5 to 1 psi above the differential pressure present when all five zones are active. At that point, flow begins to pass through the DPBV, and further upward movement of the operating point is significantly limited, as shown by the yellow points along the black line. The slight upward slope of the black line is caused by increasing head loss through the DPBV as the number of active zones decreases. The net effect of the DPBV in this system is too "approximate" the ideal scenario where there would be no change in differential pressure across the headers as zone valves open or close.

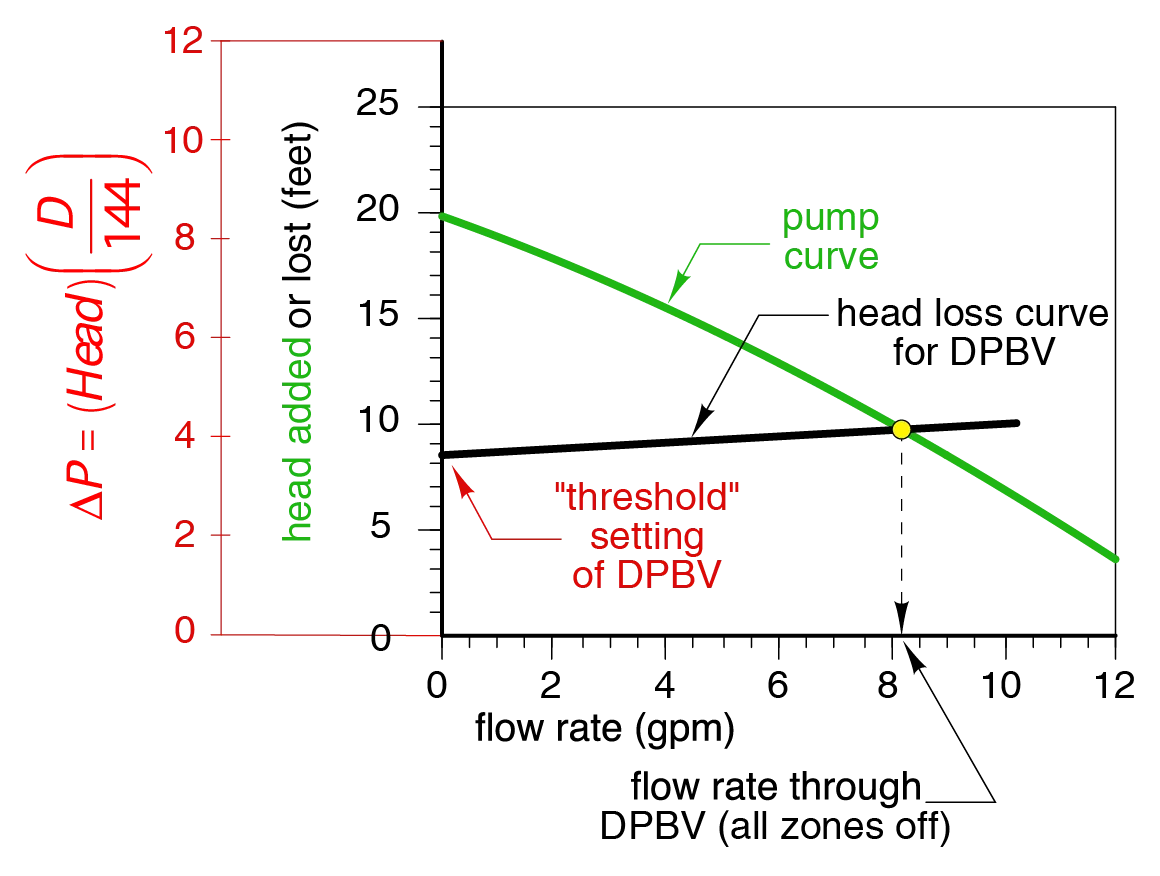

To properly size a DPBV, it's necessary to estimate the flow through it assuming all zone circuits are closed. Under this condition, it's possible to estimate the flow rate through the DPBV by plotting the head loss curve for the DPBV along with the pump curve for the fixed- speed circulator and find where they intersect, as illustrated in figure 3-7.

A vertical line drawn downward from this point indicates the flow rate through the DPBV when all the zone valves are closed. A properly sized DPBV can now be selected based on the maximum recommended flow rate for a given valve size.

Circulator technology has evolved significantly over the last several years. The common wet-rotor circulator with a permanent split capacitor (PSC) has largely been replaced by variable-speed circulators using electronically commutated motors (ECM). Most of these circulators have pre-programmed operating modes that are ideally suited for systems with valve-based zoning. Those modes include:

• Constant differential pressure control

• Proportional differential pressure control

Constant differential pressure control can be thought of as "cruise control" for differential pressure. The circulator is set for a specific differential pressure. While operating, it continually monitors the speed of its rotor, the slip of the rotor relative to the rotating magnetic field created by the motor's stator poles, and current draw. It uses these measurements, along with its firmware, to infer the differential pressure between its inlet and outlet. This inferred differential pressure is compared to the differential pressure setpoint. If the inferred differential pressure is higher than the setpoint, motor speed is reduced, and vice versa. This allows the circulator to maintain a stable differential pressure setting over a wide range of flow rates.

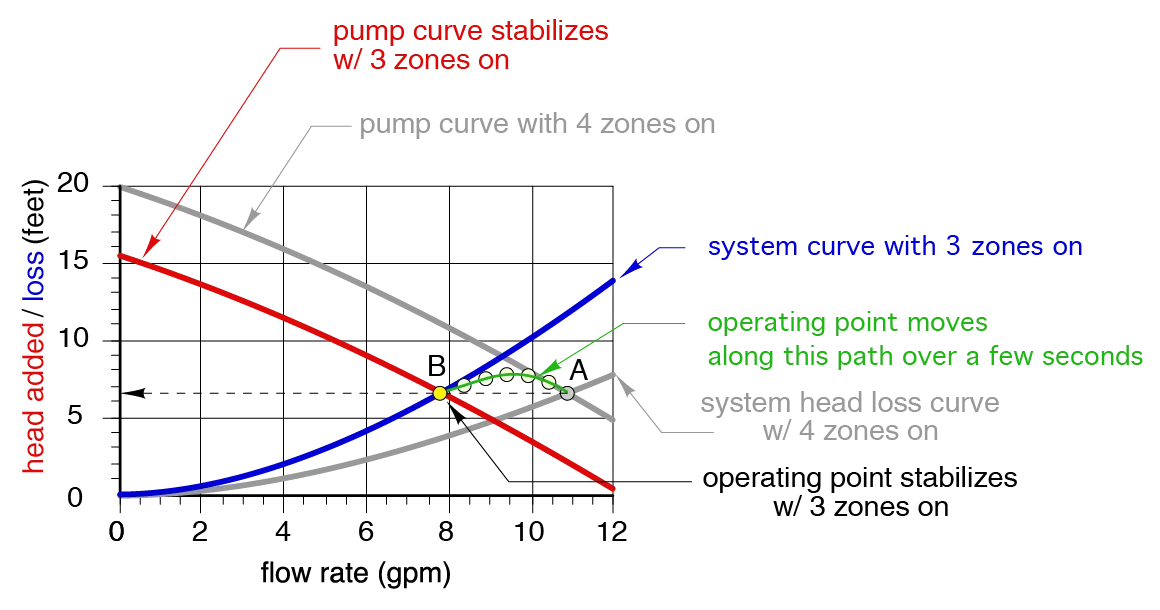

Figure 3-8 shows how a variable- speed circulator configured for constant differential pressure responds when one of the system's zone valves closes. Point A is the initial operation point (e.g., where the gray pump curve crosses the gray system head loss curve). This is the operating condition when all four zone valves in the system are open. The head added by the circulator is about 6.5 feet, and the flow rate through the circulator is about 11 gpm. When one of the zone valves closes, the system head loss curve steepens (e.g., the gray head loss curve transitions to the blue head loss curve). The circulator's internal electronics sense this change and respond by reducing motor speed, which causes the gray pump curve to transition to the red pump curve. The net effect is that the operating point moves from point A to point B. The flow rate has reduced from approximately 11 gpm to 7.8 gpm, but the head added by the circulator (6.5 feet), and thus, the differential pressure across the circulator, remains constant.

Constant differential pressure control is ideal for systems in which the pressure drop through the common piping is very small in comparison to the pressure drop through the zone circuits. The system in figure 3-9 is a good example.

The total pressure drop through the SEP4 hydraulic separator, the short headers, and the manifolds is low compared to the pressure drop through the $1/2^{\prime\prime}$ PEX circuits supplying the panel radiators.

Another operating mode for variable- speed pressure-regulated circulators is called proportional differential pressure control. When set for this mode, the circulator's internal electronics establish a mathematical line that begins at some set value of head that corresponds to the circulator operating at full speed. The line slopes downward as flow rate decreases and ends at a point corresponding to zero flow rate and a head value that's 50% of the full speed head setpoint.

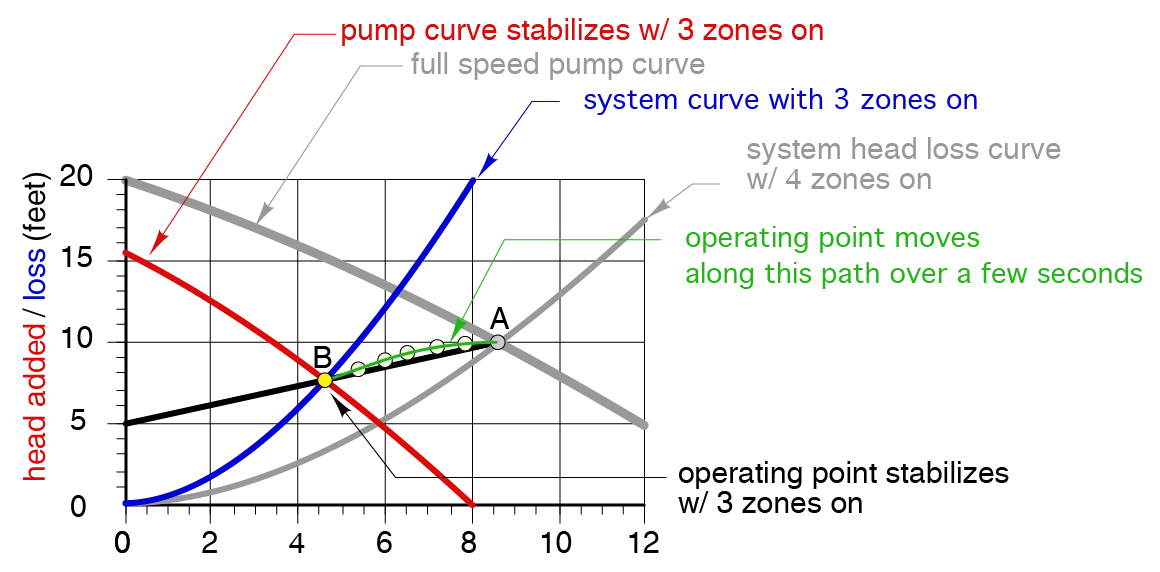

Figure 3-10 shows how a circulator set for proportional differential pressure control responds when one of the zone valves in a four-zone system closes. The circulator has been set to a head value of 10 feet, corresponding to a condition where its motor is running at full speed. The black line on the graph shows how head decreases as flow decreases. This relationship is created by idronics reducing the motor speed. The black line ends at zero flow rate and a head of 5 feet.

This control mode is intended for systems that have significant head loss in the supply and return mains that serve parallel "crossover" zone circuits. The two-pipe direct return piping system shown in figure 3-11 is one example.

Proportional differential pressure minimizes variations in differential pressure across the active zone circuits as other zones turn on and off. It compensates for the head loss across the parallel zone crossovers, as well as along the supply and return mains.

Zone valves are typically available in pipe sizes ranging from 1/2-inch to 1-1/4 inch. However, proper selection involves more than simply matching

the valve’s pipe size to the pipe it will be installed in. Two other criteria should always be evaluated when selecting zone valves:

• The valve’s Cv rating

• The valve’s close-off pressure rating

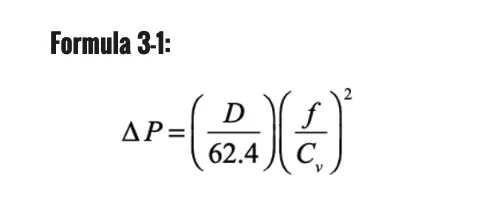

The valve’s Cv rating is the flow rate (in gallons per minute) of 60ºF water that creates a pressure drop of one psi across the valve. The relationship between the flow rate through the valve and the resulting pressure drop is based on formula 3-1.

Where:

∆P = pressure drop through valve (psi)

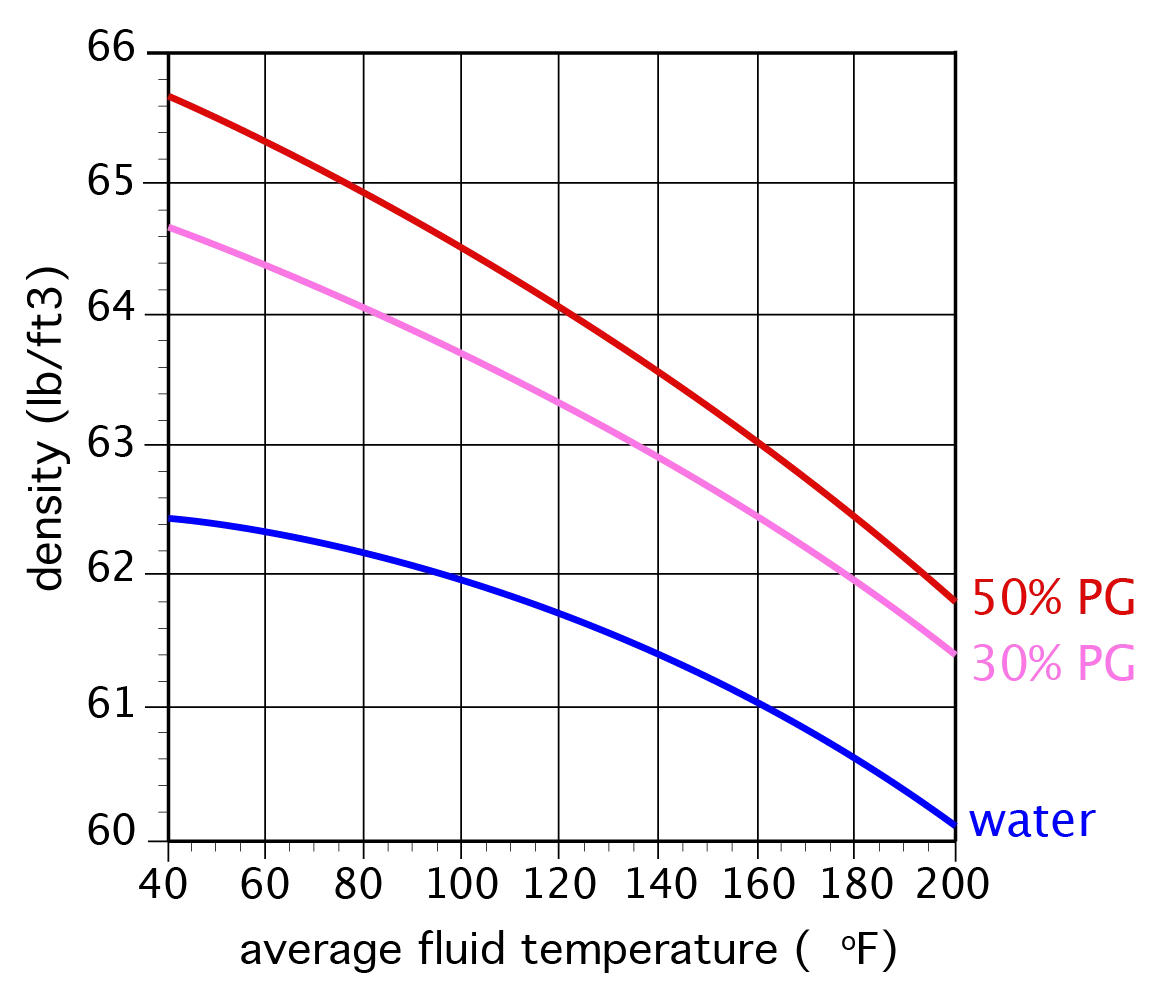

D = density of fluid flow through valve (lb/ft3)

F = flow rate through valve (gpm)

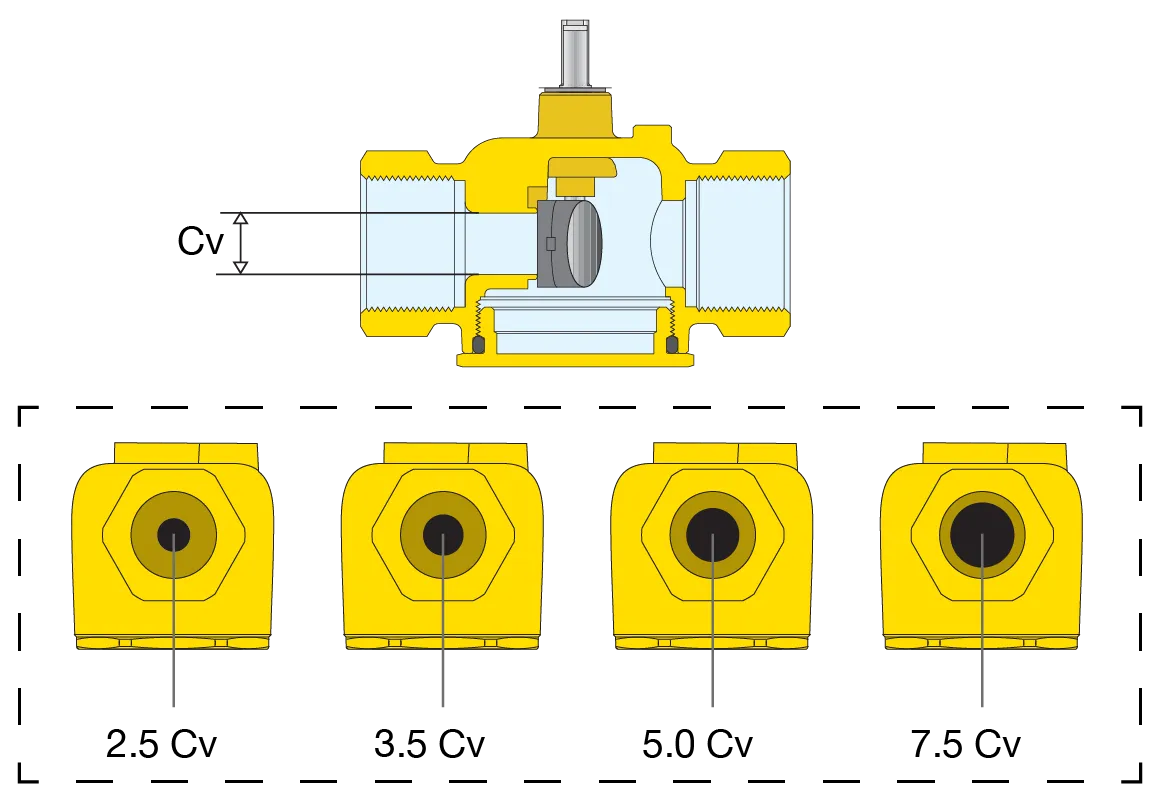

The Cv of a zone valve is partially determined by the diameter of the orifice within the valve through which all flow passes. The larger the diameter of this orifice, the higher the Cv of the valve.

Figure 3-12 shows several Caleffi zone valves having the same pipe size, but with different internal orifice diameters that affect the valve's Cv rating.

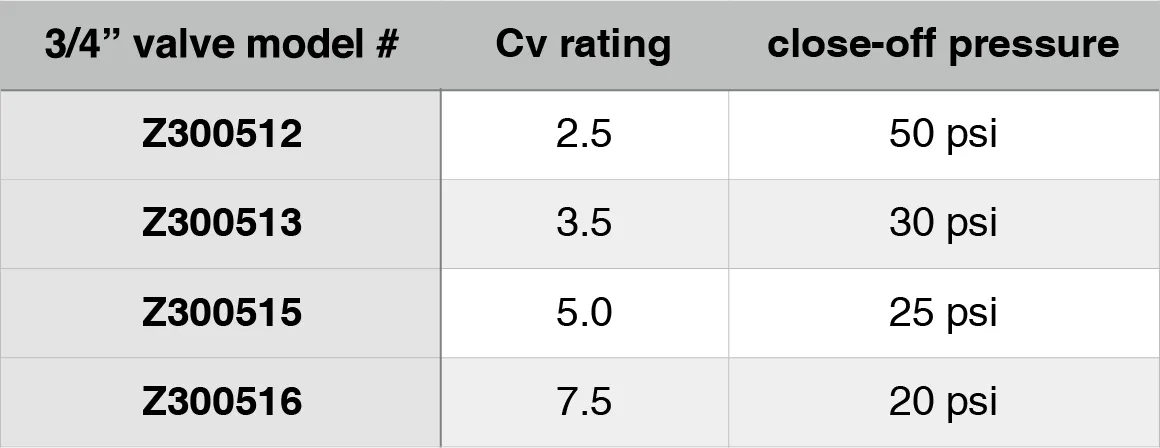

Figure 3-13 shows how several Caleffi zone valves, all with the same nominal 3/4-inch pipe size, have significantly different orifice diameters, and thus, have different Cv values.

Higher Cv ratings are beneficial because they reduce pressure drop through the valve. Lower pressure drop implies lower head loss, and thus, lower pumping power. However, as the Cv rating increases, the valve's ability to close off against a differential pressure trying to push flow through it decreases. Figure 3-13 also shows this inverse relationship between the valve's Cv rating and its rated close- off pressure.

The close-off pressure rating is the maximum differential pressure across the valve under which it can close and remain closed. If a differential pressure higher than the close-off pressure is exerted on the valve, the hydraulic force against the paddle inside the valve becomes greater than the spring force trying to hold the paddle against the valve's seat. This allows some flow through the valve. This undesirable condition can be avoided by selecting zone valves with close-off pressures slightly higher than the maximum differential pressure they could be subject to in a given system.

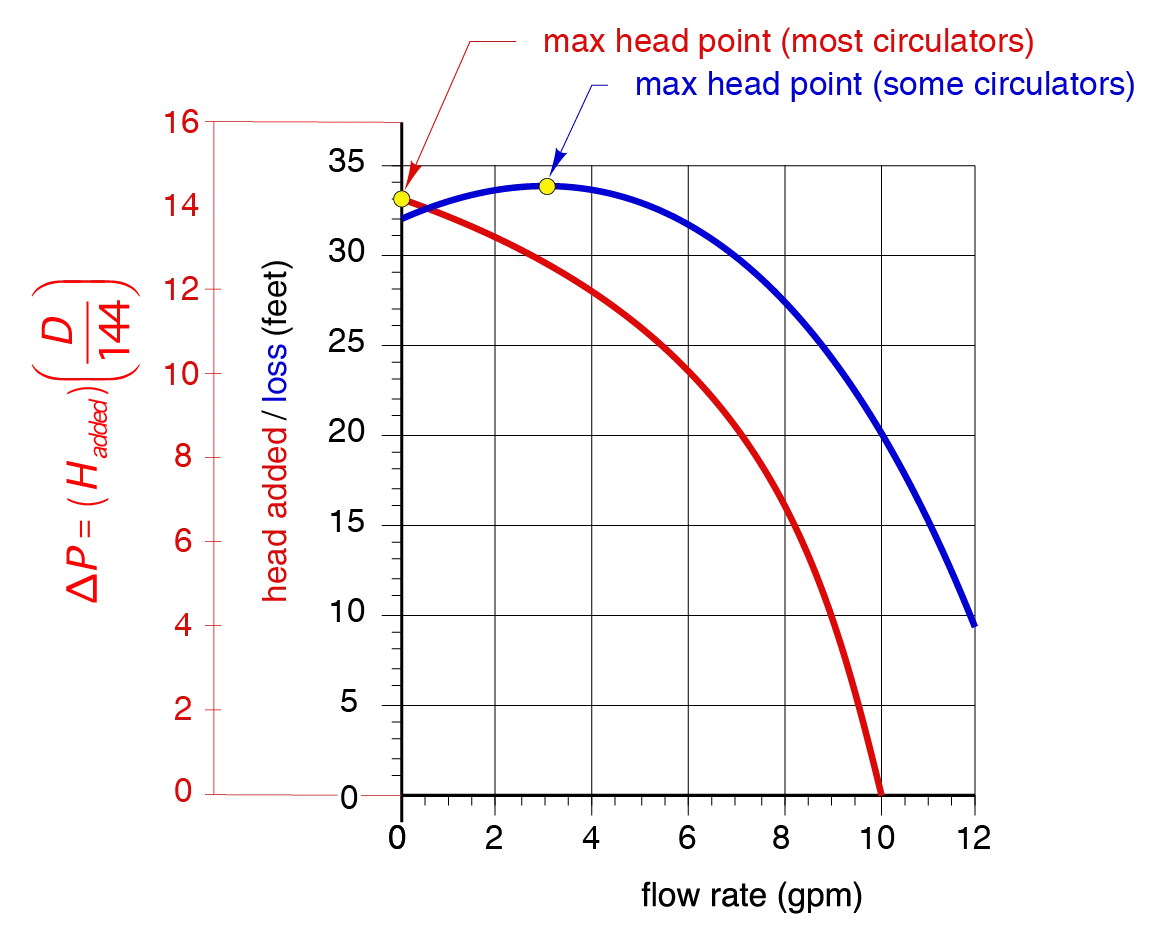

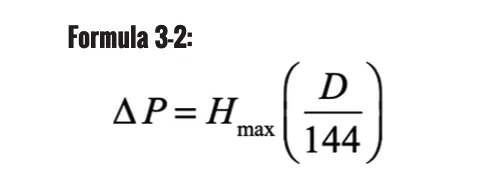

The maximum pressure differential a zone valve would experience can be conservatively estimated based on the "shut-off" differential pressure of the system's circulator. That differential pressure occurs when the circulator is operating at full speed but with zero flow rate. This pressure is found by converting the maximum head the circulator can create to a corresponding differential pressure using Formula 3-2:

The maximum head occurs at the high point of the pump curve. For most circulators, this corresponds to zero flow rate. However, some circulators may have pump curves where maximum head occurs at low but non-zero flow rates, as shown in figure 3-15.

This maximum differential pressure would only occur when the circulator is operating at its maximum speed and all zone valves in the system are closed. This condition, although possible, is uncommon, since most systems using electric zone valves do not operate the circulator unless at least one zone is active. In most systems with zone valves, the close- off pressure differential will be less than the maximum differential the circulator can create. This is especially true if a variable-speed pressure-regulated circulator is used. It's also true for systems with a properly set differential pressure bypass valve and a fixed-speed circulator.

Where:

∆P = differential pressure across circulator (psi)

Hmax = maximum head of circulator (at 0 flow rate) (feet of head)

D = fluid density (lb/ft3) (See figure 3-14)

144 = units conversion factor

ELECTRICAL DETAILS FOR SYSTEMS WITH ELECTRIC ZONE VALVES

Electrically powered zone valves are available with operating voltages of 24, 120 and sometimes 240 VAC. Of these, the 24 VAC configuration is the most common in hydronic heating and cooling systems. The electrical details to be discussed are based on 24 VAC zone valves. However, some of these details also apply to zone valves powered by 120 and 240 VAC.

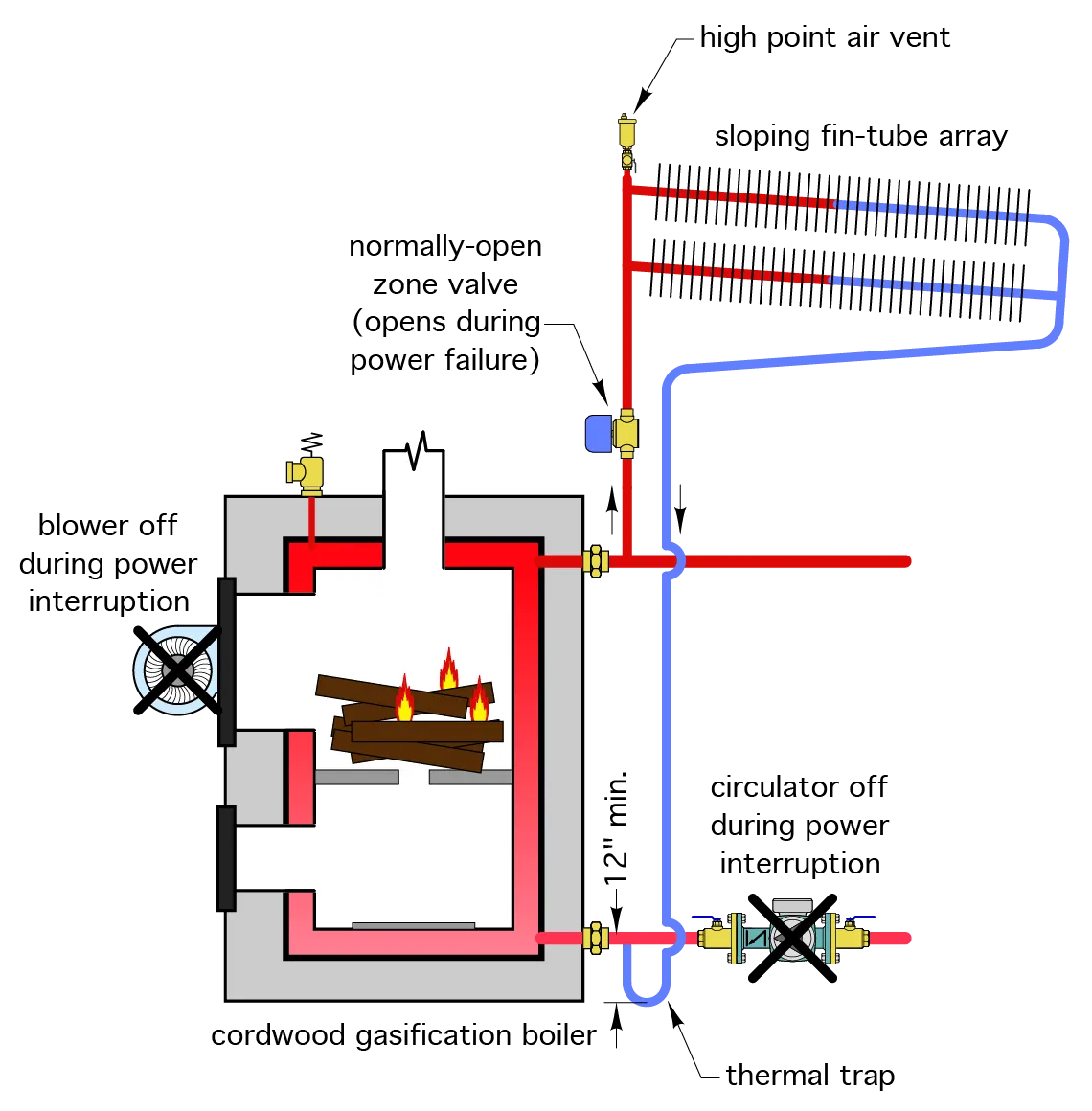

NORMALLY OPEN VS. NORMALLY CLOSED ZONE VALVES

Most zone valves are configured so they are closed when the actuator is unpowered and open when powered. These are specifically called "normally closed" zone valves. However, there are some applications in which the opposite action is required (e.g., the valve is open when the actuator is unpowered and closed when the actuator is powered). These are called "normally open" zone valves. The latter may be used in applications where it's desirable to allow flow through the valve during a power outage. One example would be a subsystem that dissipates heat from an active wood- burning boiler during a power outage. Figure 3-16 shows an example of one such application.

Some zone valves can be ordered with an end switch that closes its contacts when the zone valve is fully open. The usual purpose for this switch is to signal other equipment to operate whenever the zone valve is fully open. Examples include turning on the system's circulator and enabling its heat source or cooling source to operate.

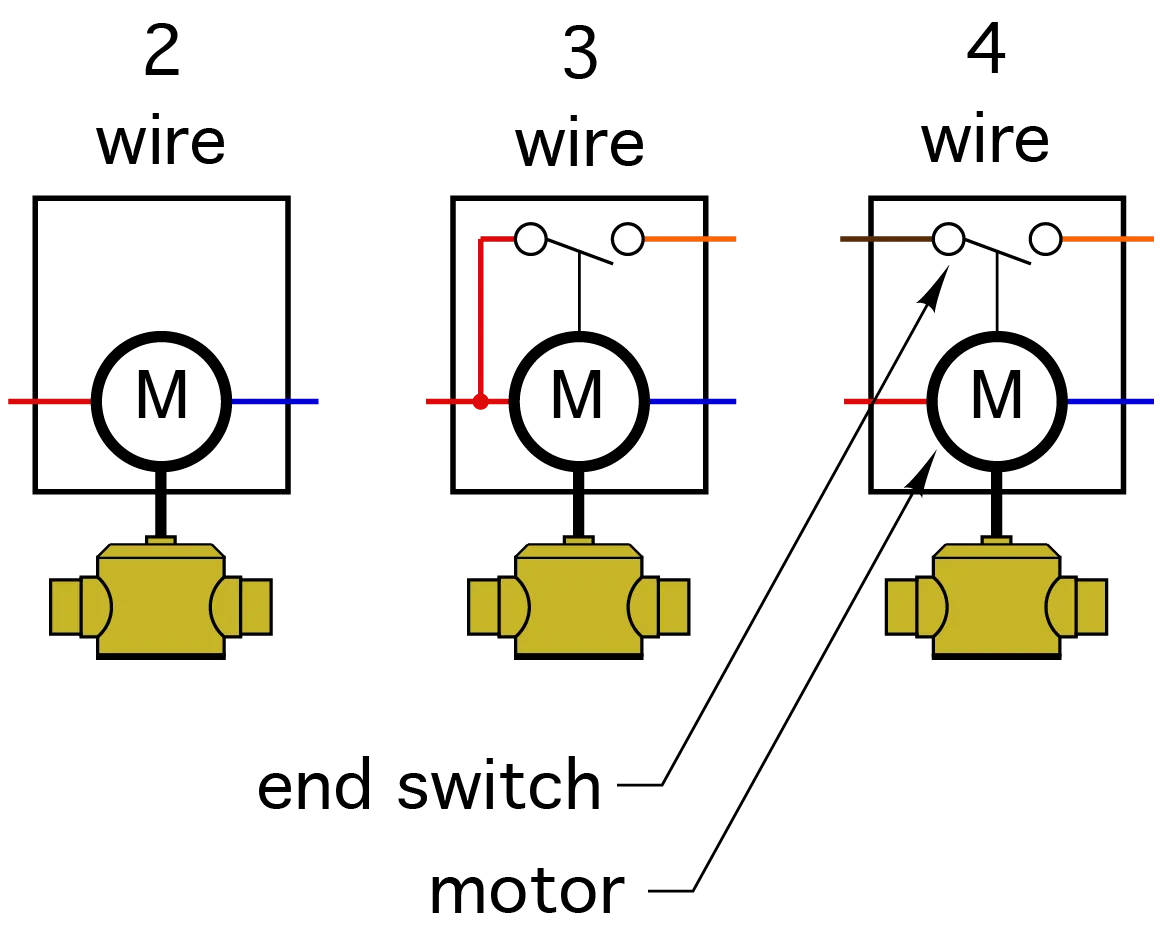

Figure 3-17 shows three internal wiring configurations for zone valves.

A two-wire zone valve has no end switch. The two terminals or wire leads on a two-wire zone valve are only used for powering the spring-return motor assembly.

A three-wire zone valve has an end switch. One contact in that end switch is connected in parallel with one power wire for the motor. The end switch closes when the valve reaches

its fully open position. The internal wiring implies that the circuit connected to the end switch must be powered by the same source as the valve's motor. This is possible, but far less versatile in terms of how the end switch is used. Three-wire zone valves have limited availability at present and are primarily used to replace older or failed three-wire zone valves.

A four-wire zone valve allows the end switch to be electrically isolated from the circuit that powers the valve's motor. This isolation allows the end switch to "signal" equipment that is powered by sources separate from the power source for the valve's motor. This greatly expands possible applications, while preserving the basic function of an end switch.

The electrical power that can be passed through a typical end switch is limited. Typical ratings are for a maximum current of 0.4 amp in a 24 VAC circuit. This is sufficient for common low-voltage switching applications for which the end switch is intended. It is not adequate for any type of line voltage switching. See idronics 14 for more information on wiring for electrical zone valves.

Caleffi Z-One zone valves are rated to work with fluid temperatures down to 32°F. When applied in chilled water cooling systems, the fluid temperatures are usually in the range of 45 to 55°F. When operating at these temperatures, the valve body is typically below the dewpoint temperature of surrounding air. This creates the potential for condensation to form on the valve body. To avoid this, the body of the valve should be wrapped with insulating foam tape. However, the valve's actuator should not be insulated. Figure 3-18 shows an example of chilled water piping where the piping and valve body are wrapped with elastomeric foam insulation, but the valve actuator is not insulated.

Systems using zone valves typically use a low-voltage (24 VAC) thermostat in each zone to signal when a zone valve should open or close. A line voltage circulator must also be turned on whenever one or more thermostats call for heating or cooling. The heat source or chilled water source must also be enabled to operate whenever one or more zone thermostats are calling for heating or cooling. Some systems also require one zone to have "priority" over other zones. When the priority zone is active, the other zones are temporarily turned off, at least for some predetermined time.

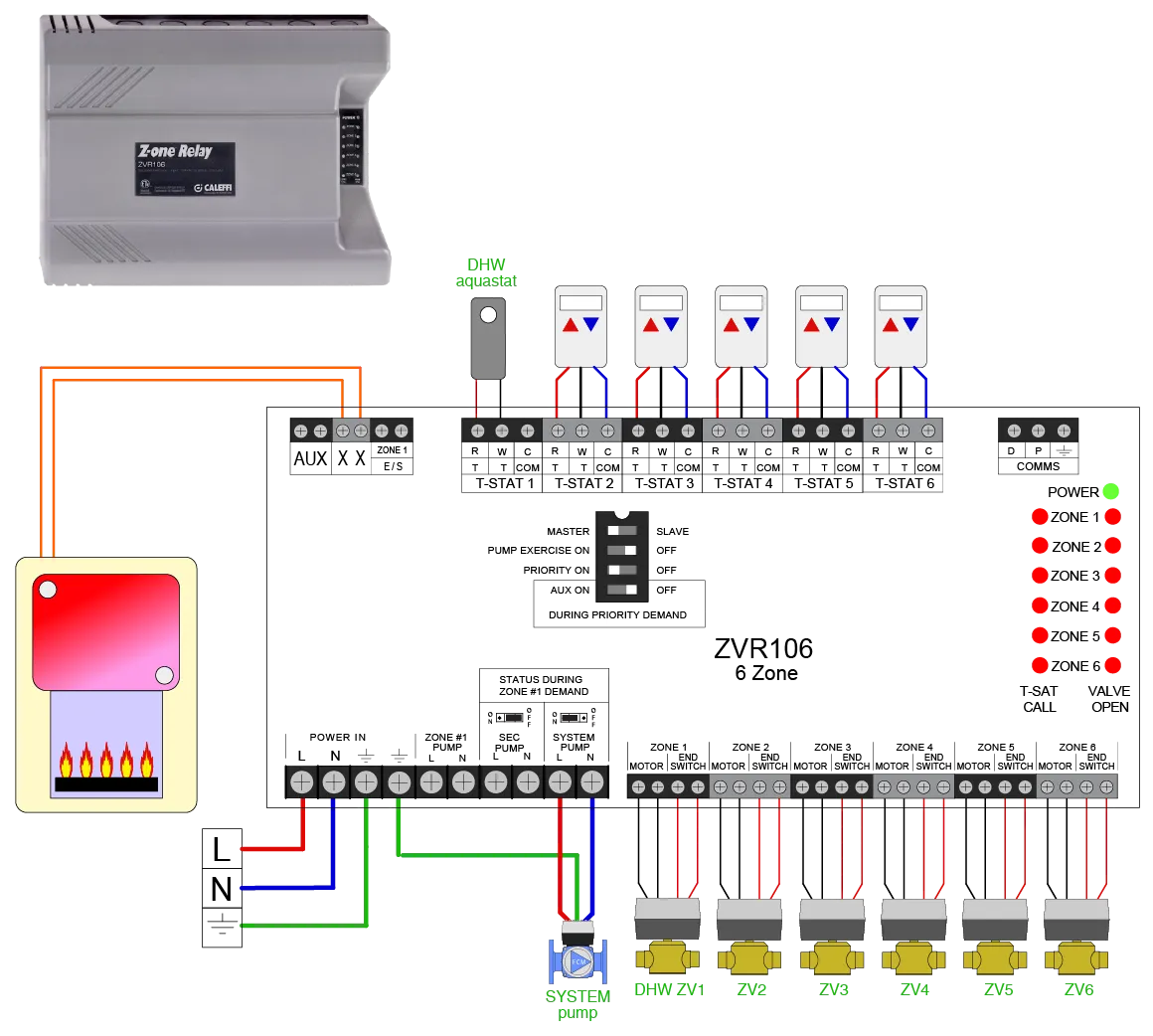

The most convenient, simplest and most cost-effective approach to accomplishing these control functions is by using a Multi-Zone Valve Control. Figure 3-19 shows one of several wiring configurations on a Caleffi ZVR106 Multi-Zone Valve Control.

The Caleffi ZVR106 Multi-Zone Valve Control provides wire "landing" terminals for up to six zone thermostats. When a heating call is received from a specific thermostat, the control powers on the associated zone valve and signals the heat source to operate. See idronics 14 for more information on Caleffi multi-zone controls.

MOTORIZED BALL ZONE VALVES

The previously discussed electric zone valves have actuators with small AC motors that turn a gear train to rotate the valve's shaft. When power is removed from a normally closed actuator, a spring assembly unwinds to rotate the shaft in the opposite direction to close the valve. This type of valve is sometimes referred to as power open/ spring closed.

In some applications, the valve controlling flow through a zone circuit needs to have a higher Cv rating than what might be available with a typical power open/spring closed zone valve. The valve might also need to close against a higher differential pressure than is possible with a spring return valve. In these situations, a motorized ball valve with a power open/power close actuator can provide both requirements.

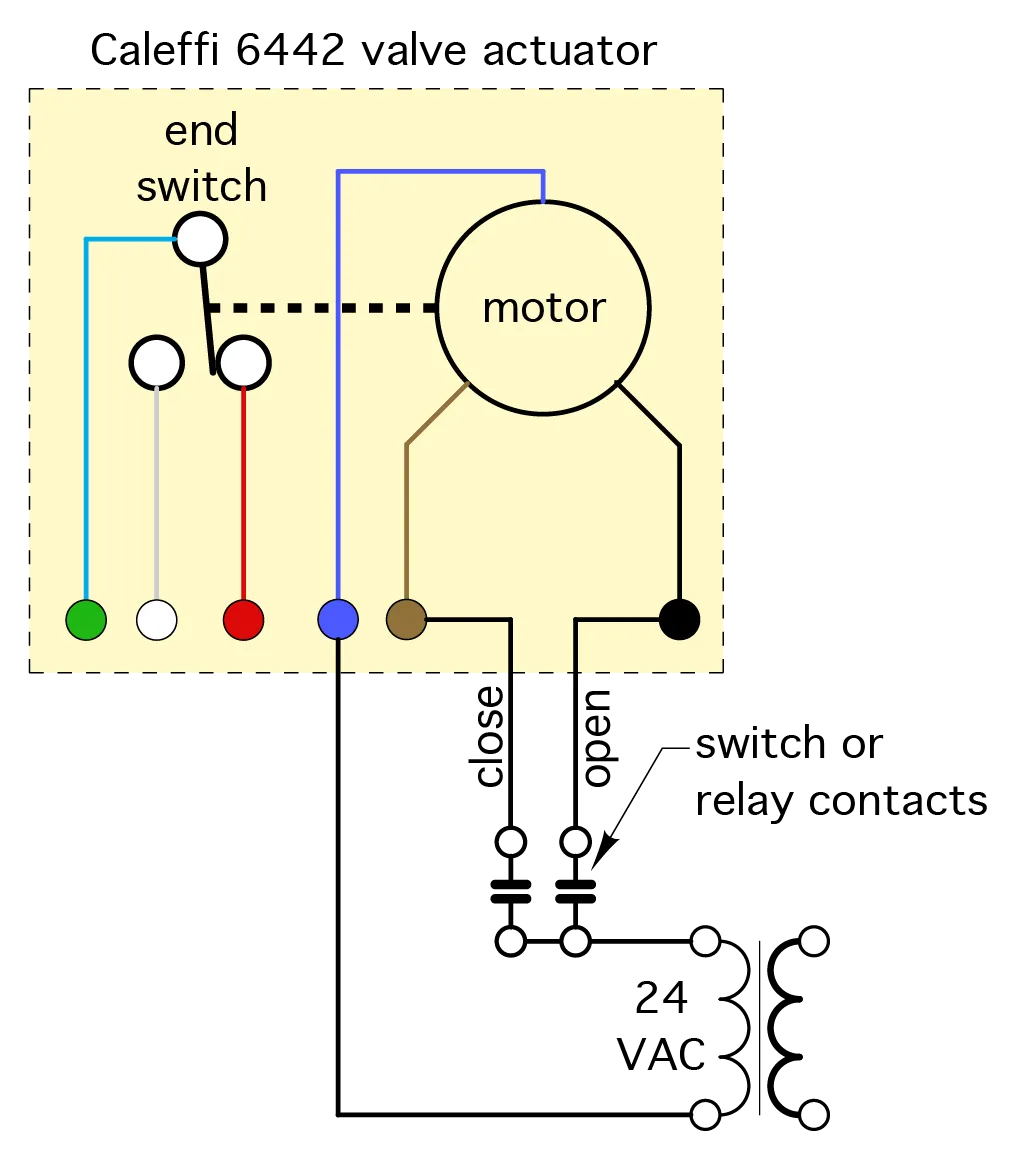

Figure 3-20 shows an example of a Caleffi 6442 motorized ball valve that has a power open/power close actuator.

Figure 3-21 shows how external 24 VAC wiring connects to the valve.

The blue lead from the 6442 actuator connects to one side of a transformer that provides 24 VAC secondary voltage to operate the valve’s motor. When the other side of the transformer is connected to the brown lead of the actuator through a switch or relay contact, the motor closes the ball

valve. When this same side of the transformer is connected to the black lead of the actuator through a switch or relay contact, the ball valve opens. When neither the brown nor black lead is powered, the valve holds its current position.

These valves require approximately 40 seconds to rotate the ball valve through 90º between fully open and fully closed, or vice versa. During this operation, the valve motor requires about four watts of power input. When the ball valve reaches its fully open or fully closed position, an internal microswitch stops further power input. Thus, unlike a spring-return zone valve, no power is required to hold the valve in its fully open position.

The actuator on the Caleffi 6442 valve also has an internal single pole double throw (SPDT) switch. The green lead on the cable connects to the common terminal of this switch. The red lead connects to the normally closed contact. There is electrical continuity from the red to the green lead when the valve is fully closed. The white lead connects to the switch’s normal open contact. There is electrical continuity from the white to the green lead when the valve is fully open. These switch contacts can be wired to other controls in the system to verify the open versus closed status of the valve. They can also be left unconnected if there is no need for open versus closed verification. These switch contacts are rated for a maximum current of 5 amps in a 24 VAC circuit.

The Caleffi 6442 has a Cv rating of 13 and can close against a differential pressure of up to 150 psi. These valves are ideal for applications where high close off pressure, high Cv and low electrical power demand are needed.

The Caleffi 638 valve, shown in figure 3-22, is also a motorized ball valve with the same type of wiring as the 6442. It's available in pipe sizes from 3/4-inch up to 2-inch. The latter has a Cv rating of 162. The 638 valve is also configured with a Posi-Stop™ body, which allows it to be matched with union tailpieces that connect to sweat copper, MPT or press copper. These valves are ideal for higher flow rate applications in heating or cooling systems.