One common approach for zoning a hydronic heating or cooling system is based on using a separate circulator for each zone circuit. The circulator is turned on when a thermostat located within the zoned space calls for heat or cooling. When the thermostat reaches its setpoint temperature, the circulator is turned off.

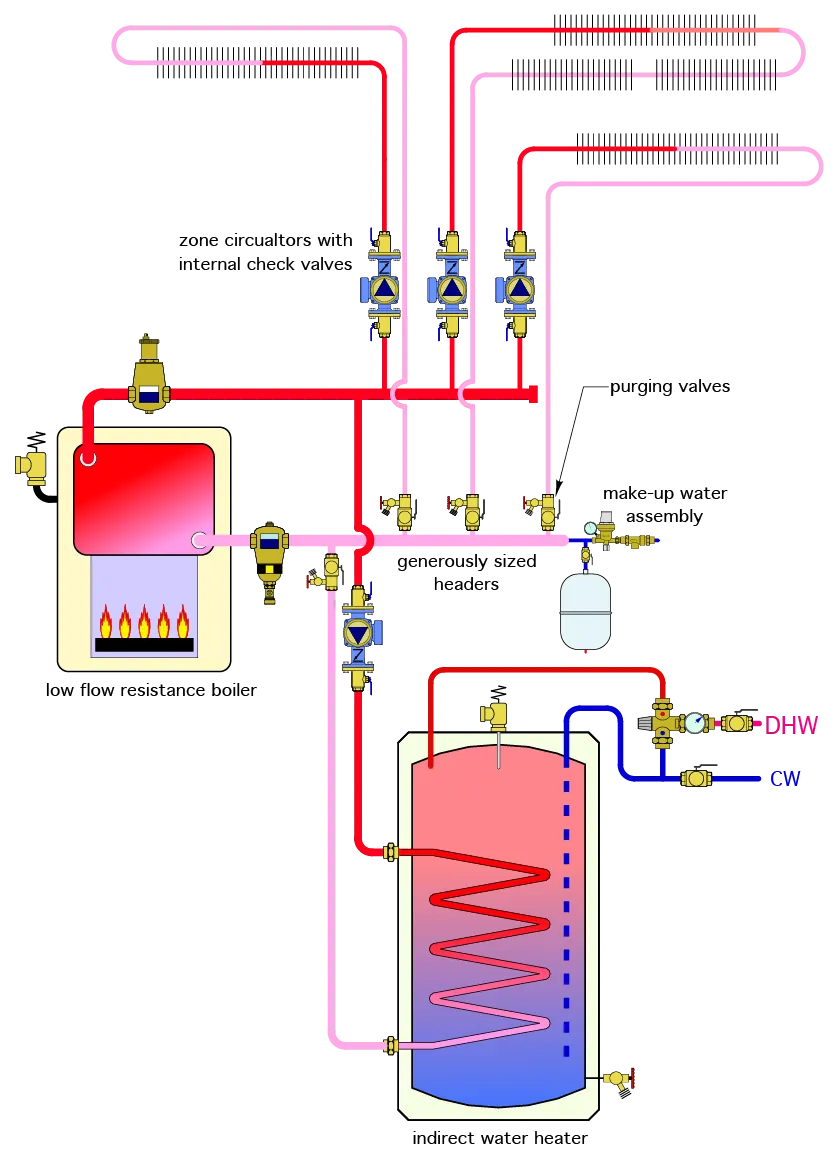

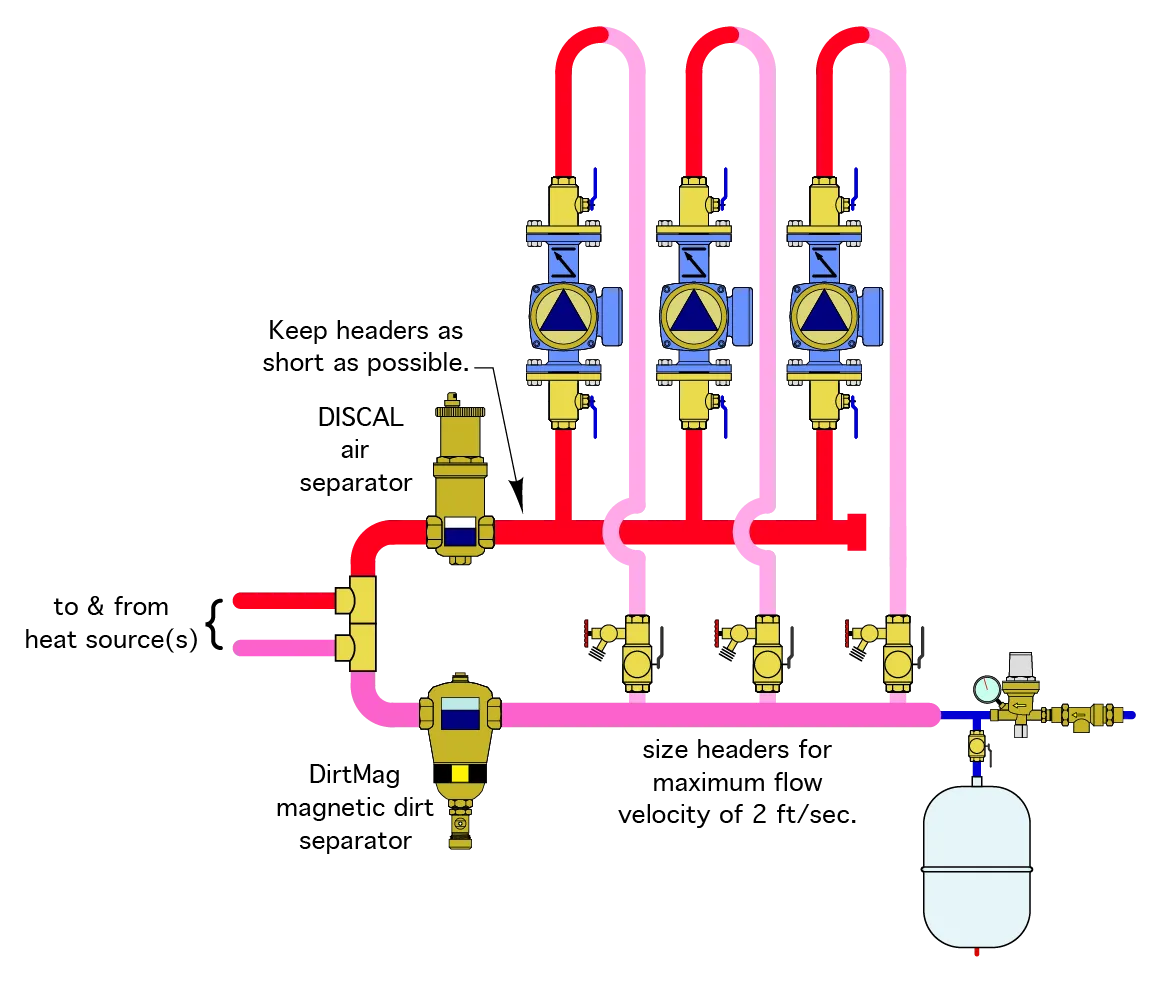

Figure 2-1a shows two common piping arrangements for a four-zone system.

The system in figure 2-1a assumes that the heat source has very low flow resistance. A cast iron boiler is an example of such a heat source. A buffer tank that temporarily stores heat from some other source is another. In such systems, all zone circuits begin and end at headers that connect directly to the heat source or buffer tank.

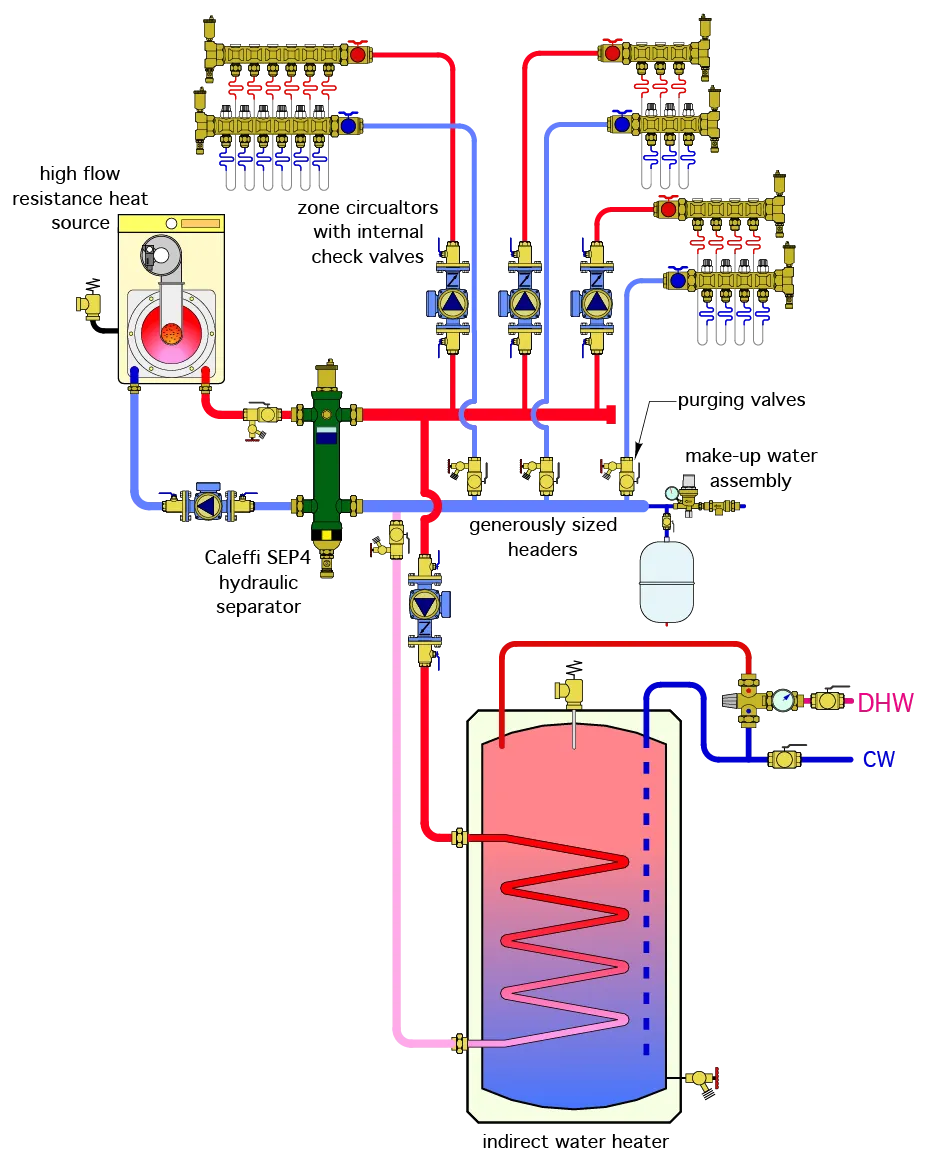

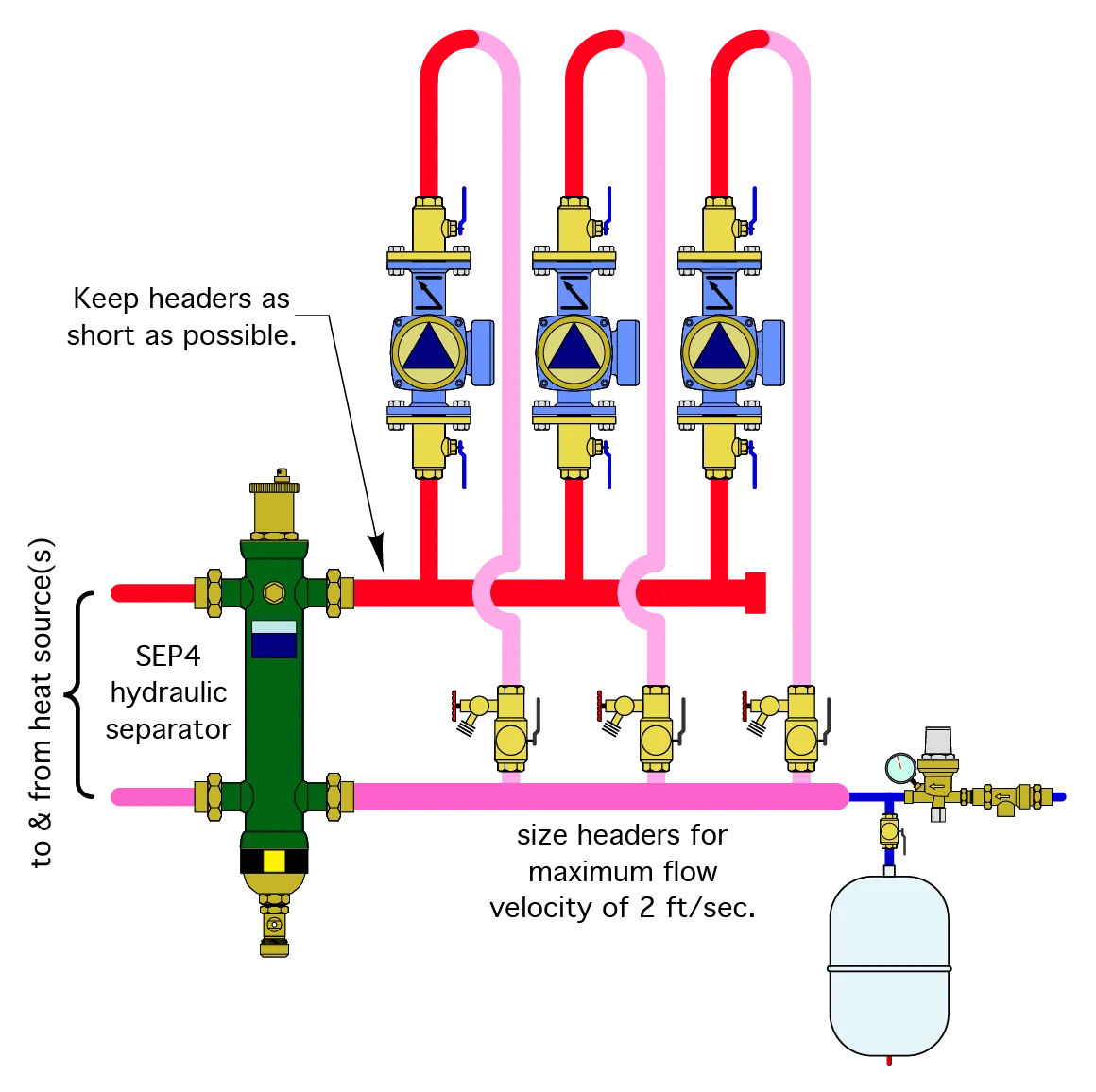

The system in figure 2-1b assumes a heat source with high flow resistance, such as certain modulating/ condensing boilers, or a hydronic heat pump. The headers connect to a hydraulic separator. The heat source has its own dedicated circulator.

In both systems, three of the four zone circuits supply space heating, while the fourth zone supplies an indirect water heater.

One advantage of using zone circulators is that the failure of one circulator doesn't interrupt heat delivery to the other zones. If the circulator that failed was installed with valves on both its inlet and outlet, it can be quickly isolated, removed and replaced within a few minutes.

Another advantage of zoning with circulators is the ability to size each circulator to the flow and head requirements of its associated zone circuit. Contrary to what is often assumed, all the zone circulators in a system don't have to be the same make or model. Multi-speed circulators can be set for lower flow and head requirements in small or short zone circuits. They can also be set for higher flow and head requirements in large or long zone circuits. If the speed settings available on a multi-speed circulator are unable to provide the hydraulic needs of a given zone, a different circulator can be used.

One major disadvantage of zoning with circulators is that the electrical power required, especially with all zones operating, typically exceeds that required for an equivalent system using valve-based zoning. This can be demonstrated by calculating the distribution efficiency of a system with zone circulators to that of an equivalent system using zone valves.

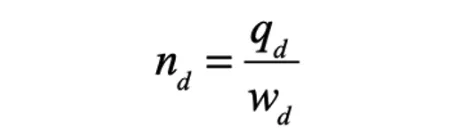

Distribution efficiency is defined as follows:

nd = distribution efficiency

qd = rate of heat delivery at design

load (Btu/hr)

wd = wattage required to operate the

distribution system at design load

(watts)

The higher the distribution efficiency, the greater the rate of heat delivery per watt of input power to operate the distribution system. Distribution efficiency is not, in any way, related to the thermal efficiency of the system's heat source. It is solely determined by the design and components used in the distribution system.

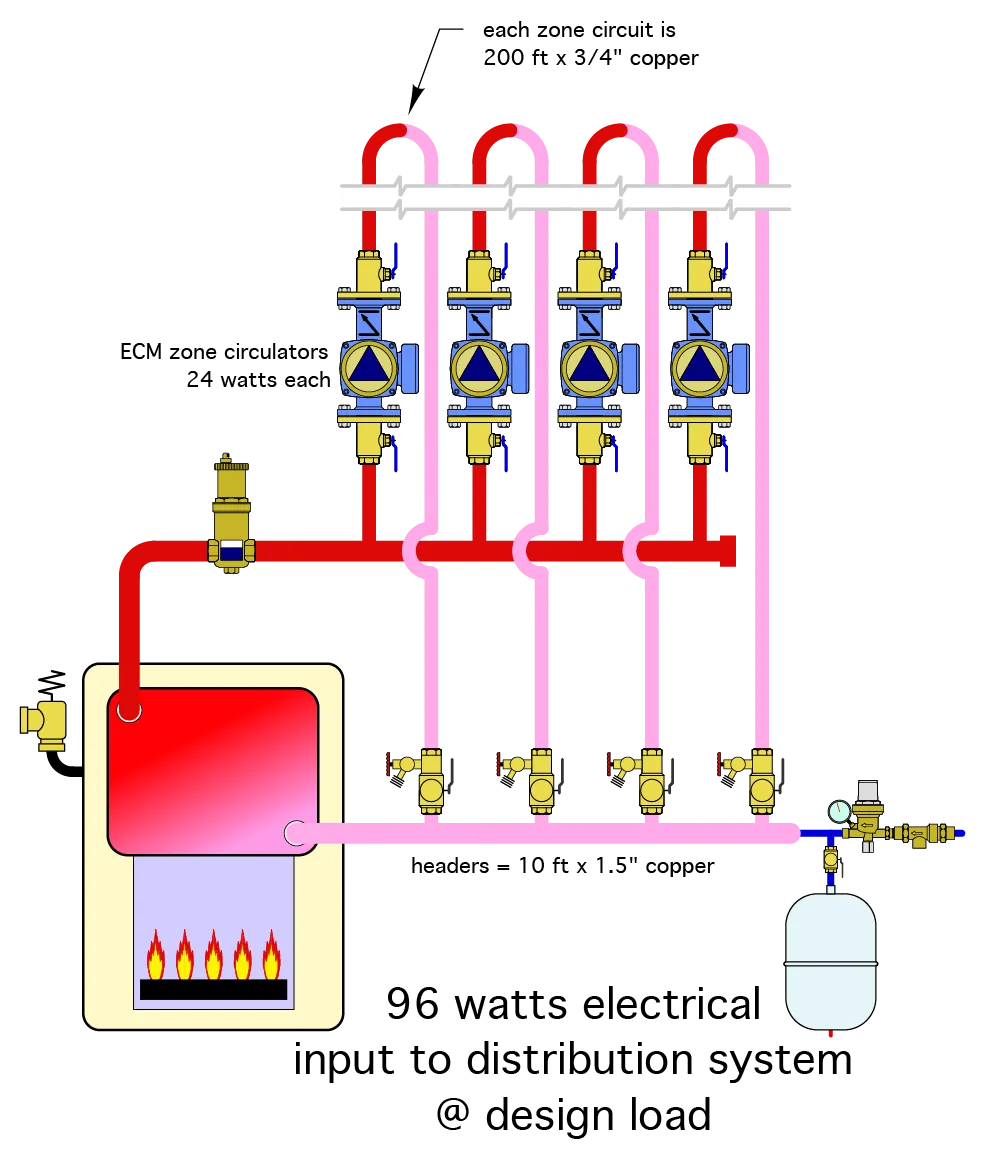

Consider a four-zone system where each zone circuit is powered by a modern zone circulator with an ECM motor, as shown in figure 2-2a.

Assume that each zone circuit has the equivalent length of 200 feet of 3/4-inch copper tubing and operates with water supplied at 130°F. Each zone delivers 5,000 Btu/hr at design load. Under these conditions, the estimated power input to each zone circulator when it's operating is 24 watts. With all four zones operating, the total estimated power input to the distribution system is 96 watts.

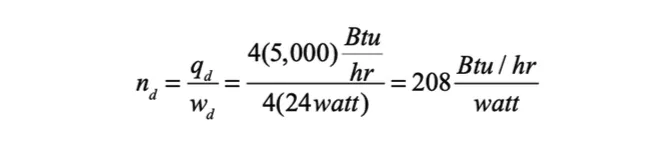

The distribution efficiency of this system would be:

The calculated value of distribution efficiency (e.g., 208 Btu/ hr/watt) can be interpreted as follows: For each watt of electrical power supplied to operate this distribution system, it delivers $208~Btu/hr where it needs to go in the building.

The distribution efficiency of this system would be:

The calculated value of distribution efficiency (e.g., 208 Btu/hr/watt) can be interpreted as follows: For each watt of electrical power supplied to operate this distribution system, it delivers 208 Btu/hr where it needs to go in the building.

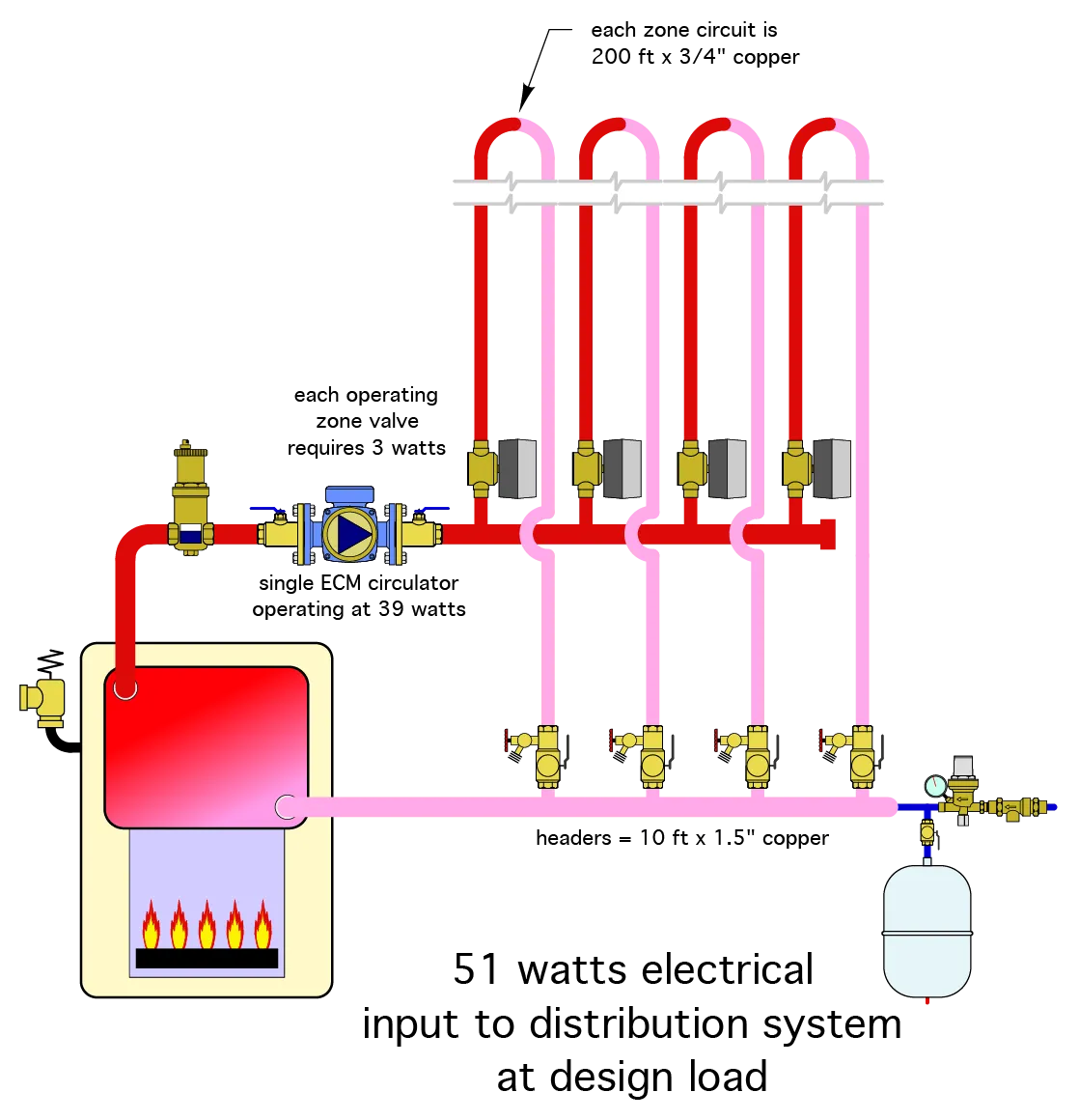

If these four zone circuits were instead supplied by a single circulator of the same make and model as the four zone circulators, along with valve-based zoning, the estimated power input to that circulator with all zones operating is 39 watts. Adding another three watts each for four operating zone valves brings the total wattage for the distribution system at design load to 51 watts (figure 2-2b).

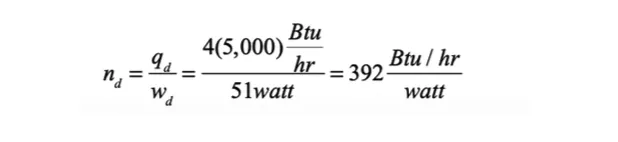

The distribution efficiency of the zone valve system would be:

In this comparison, the system using valve-based zoning delivers about 88% more heat per watt of electrical input, compared to the system using zone circulators.

Systems using circulator zoning, but with a very high number of zones, can have low distribution efficiency. This is especially true if the zone circulators have permanent split capacitor (PSC) motors. Consider a system similar the one shown in figure 2-3, courtesy of the Radiant Professionals Alliance.

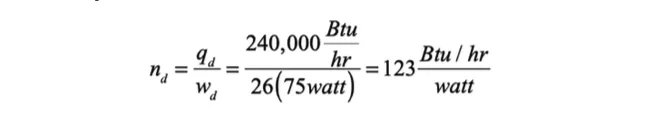

Although the workmanship appears excellent, this system has 26 zone circulators with PSC motors. Each circulator has an estimated input power of 75 watts. Assume that the distribution system delivers 240,000~Btu/hr at design load conditions with all 25 circulators operating.

This distribution efficiency is significantly lower than either of the previous examples. Converting the circulators to new models with ECM rather than PSC motors would improve the distribution efficiency, but it's likely to remain well below that of a similar system using zone valves and a single ECM circulator, especially if that single circulator has pressure- based variable-speed control.

Another potential disadvantage of zoning with circulators is the need for line voltage wiring to each circulator. Some building or electrical codes may require that wiring to be routed through conduit and installed by a licensed electrician. In contrast, most electrically operated zone valves only require 24 VAC wiring, which typically doesn't have to be run through conduit or installed by a licensed electrician. This helps reduce installation cost.

The distribution efficiency of the zone valve system would be:

DETAILS WHEN ZONING WITH CIRCULATORS

There are several design and installation details that help ensure reliable and efficient performance of systems using zone circulators. One is the use of spring-loaded or weighted-plug check valves in each zone circuit. These valves serve two purposes:

1. They prevent hot water from migrating into inactive zone circuits. Without this provision, hot water will thermosiphon upward into zone circuits when the associated zone circulator is off. This effect is caused by the difference in density between "hot" water in the heat source and adjacent piping, and cooler water on the return side of the circuit. A typical swing check valve cannot prevent this undesirable effect. However, a spring-loaded check valve, such as the Caleffi 3047 serviceable low-lead check valve, or the weight of the plug in an older style "Flo Control" valve, both provide approximately 0.5 psi forward opening resistance. This is typically sufficient to prevent thermosiphon flow.

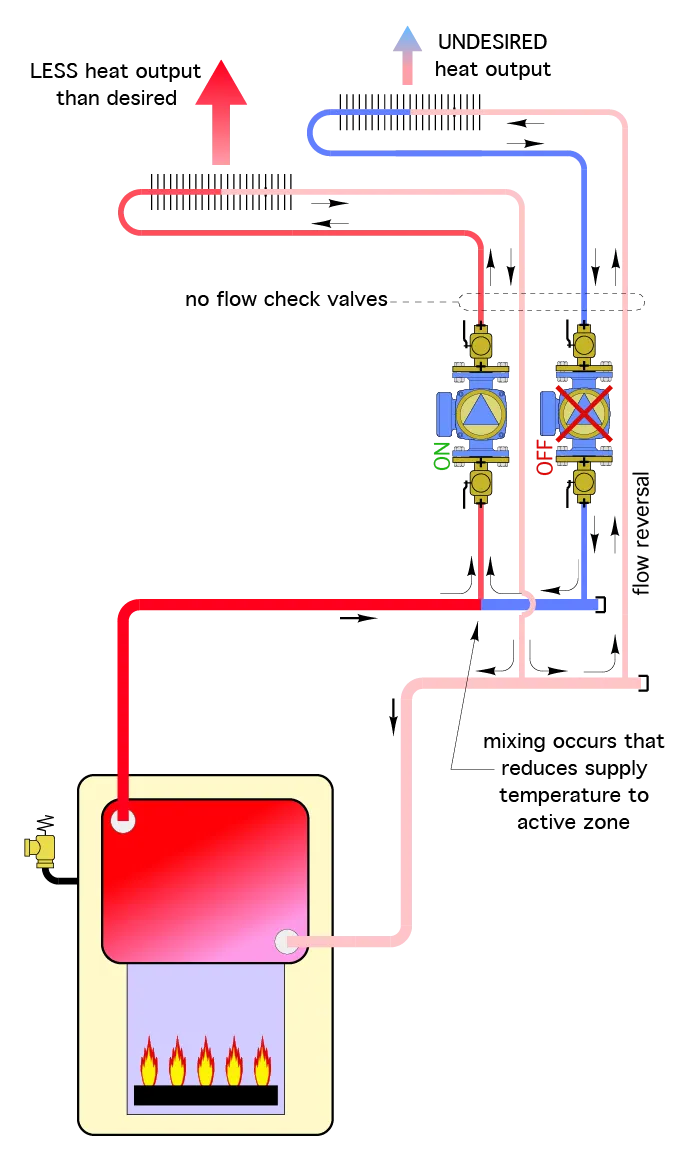

2. They prevent flow reversal through inactive zone circuits when other zones are operating. Figure 2-5 shows how such flow reversal would otherwise occur if check valves were not present in each zone circuit.

Flow reversal through inactive zone circuits creates undesirable heat output in spaces that don't need that heat. It also causes a mixing effect in the supply header that reduces the water temperature supplied to the active zone circuits, which reduces heat output from the heat emitters in those circuits.

Many of the wet-rotor circulators currently sold for zoning in residential and light commercial hydronic systems come with spring-loaded check valves that fit into the discharge port of the circulator's volute. If a circulator with an integral check valve is installed in vertical pipe with upward flow, it is essential to thoroughly purge the circuit to prevent air from being trapped within the circulator's volute.

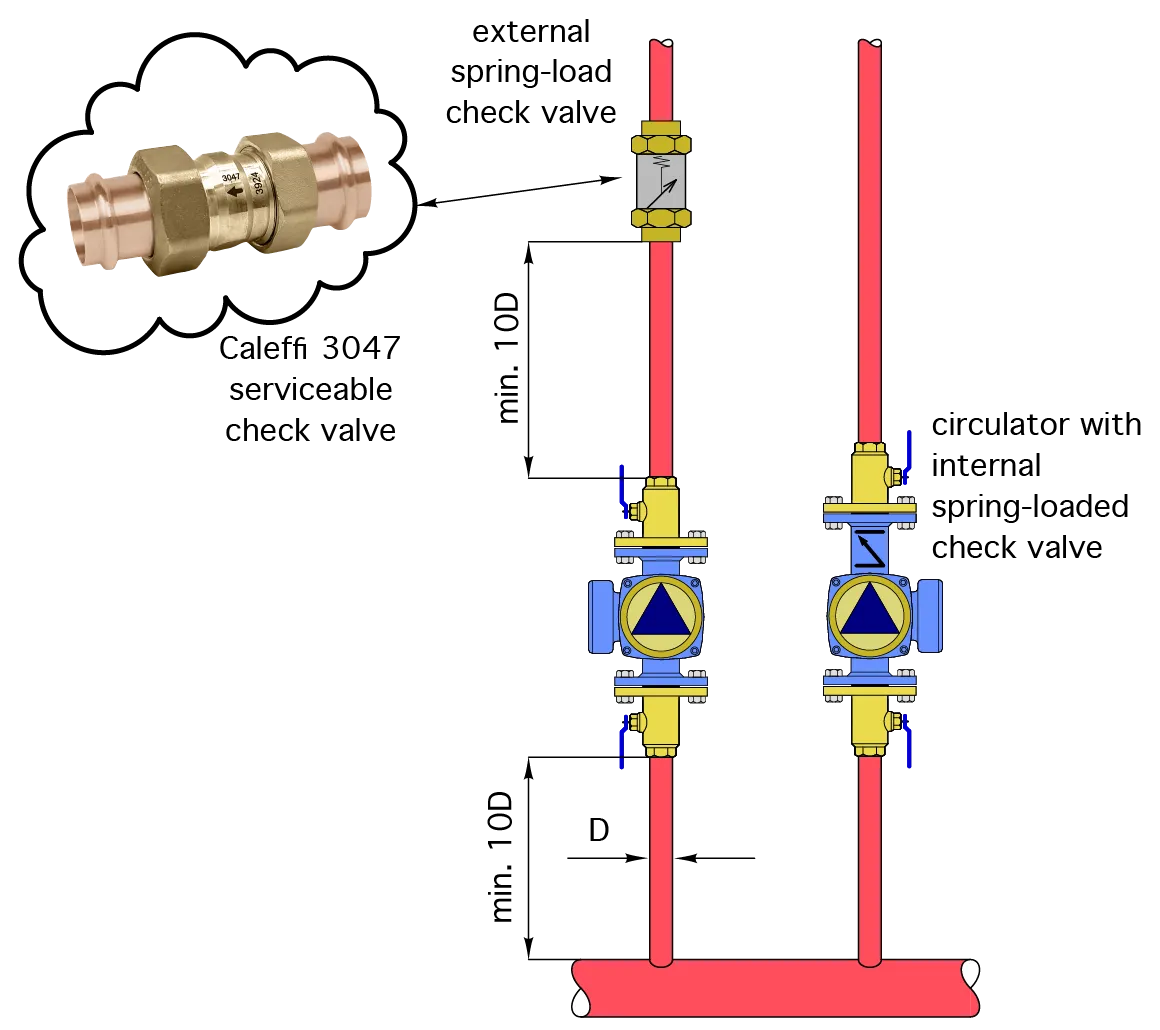

It's also possible to install a spring- loaded check valve downstream of the circulator, as shown in figure 2-6.

When installing circulators, it's important to plan for a minimum length of straight pipe on the inlet side of the circulator. The suggested minimum length is 10 times the nominal diameter of the pipe. This reduces turbulence in the flow stream before it enters the circulator, suppressing flow noise and reducing the possibility of cavitation under certain conditions.

The same minimum straight pipe length of 10 times the pipe diameter should be present upstream of any check valve. This reduces the potential for oscillations in the check mechanism. It also allows air bubbles to rise up and out of the circulator's volute, reducing the possibility that the circulator cannot clear itself of air.

It is possible for dirt, solder balls, pieces of teflon tape or other debris to get entangled with the spring assembly or the seat in a check valve. This can prevent full closure of the valve and partially negate its intended functions. Caleffi offers a serviceable spring check valve which can be easily disassembled to clear any such debris.

The 3047 is available in pipe sizes up to 2-inch and with several types of pipe connections (e.g., solder, press, FPT threaded or PEX).

IMPORTANCE OF HYDRAULIC SEPARATION

Systems with circulator-based zoning have at least two circulators. Depending on the size of the building and how it is divided into zones, there can be four, six, even 12 or more zones, each powered by a separate independently controlled circulator.

Designers often plan for each zone to operate at some target flow rate. Those flows are usually calculated independently for each zone, based on the load, the desired temperature drop under design conditions, and the type of heat emitters used.

In an ideal scenario, the intended flow rate for each zone would remain unaffected by the on/off status of other zones in the system. If the target flow rate for zone 1 is four gpm, that flow rate should be maintained in zone 1 when it's the only zone operating, and when any one or more of the other zone circulators are operating.

Whenever two or more circulators are used in the same system and are capable of operating at the same time, it's important that the pressure dynamics created by one circulator do not interfere with those created by another circulator. This effect, when achieved, is called hydraulic separation. Understanding the concept of hydraulic separation is an essential prerequisite to designing hydronic systems that perform as expected.

Achieving hydraulic separation starts by first identifying the piping and components that are "common" or "shared" by all circuits having circulators. This portion of the system will be called the "common piping." Once identified, the design goal is to make the head loss of the common piping as low as possible.

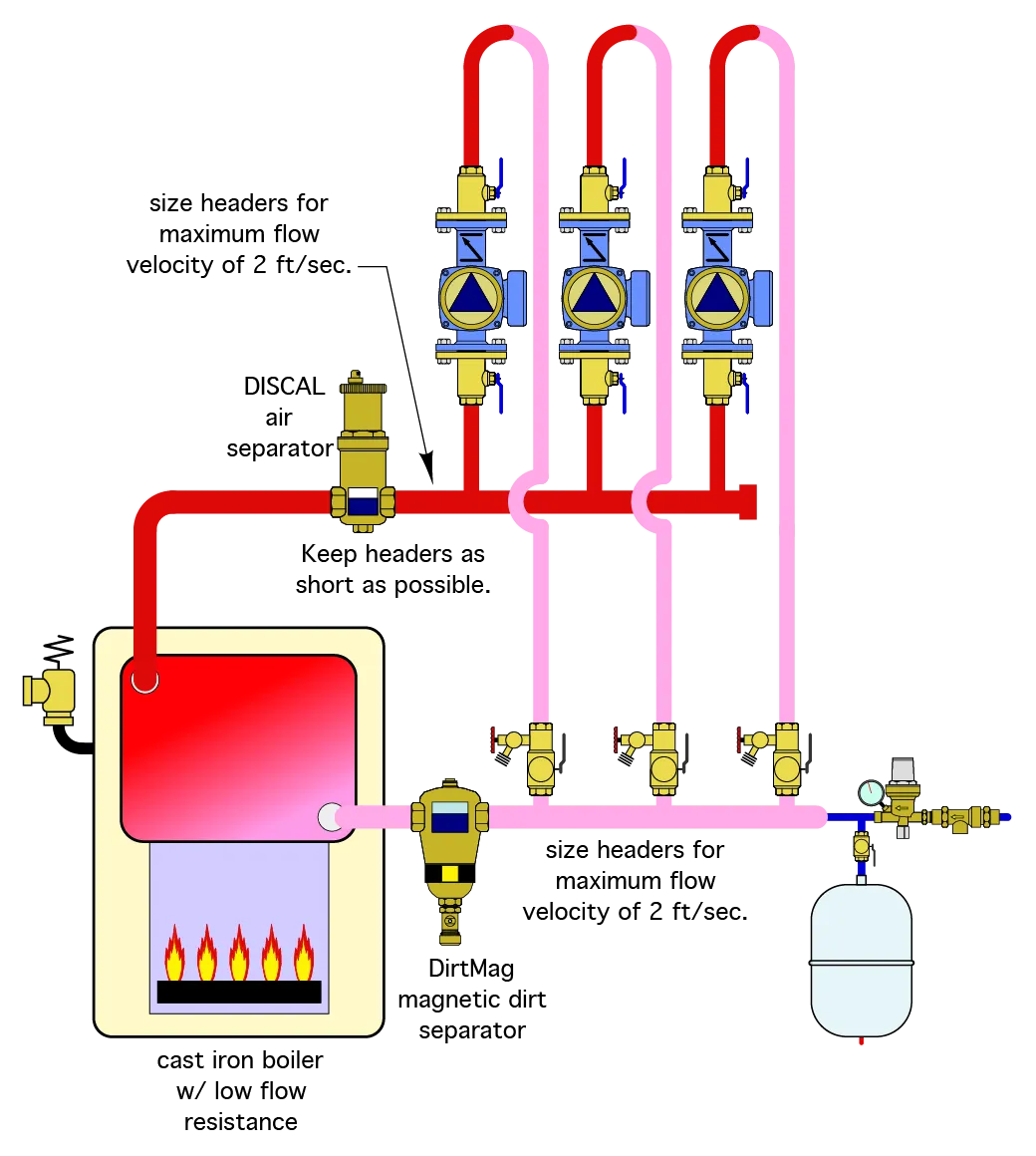

There are several design techniques and component options that can be used to establish hydraulic separation. In systems using zone circulators and low-flow-resistance heat sources, such as cast iron boilers, hydraulic separation can be achieved by keeping the headers supplying the zone circuits generously sized and as short as possible, as shown in figure 2-7.

The headers should be sized for a maximum flow velocity of two feet per second, assuming that all zones are operating. This, along with keeping the headers as short as possible, creates minimal head loss. Most cast iron boilers have very low flow resistance due to the large open flow chambers in the cast iron sections. The headers combined with the boiler represent the piping that is common to all three zone circuits. Since the flow resistance of that common piping is low, hydraulic separation is achieved.

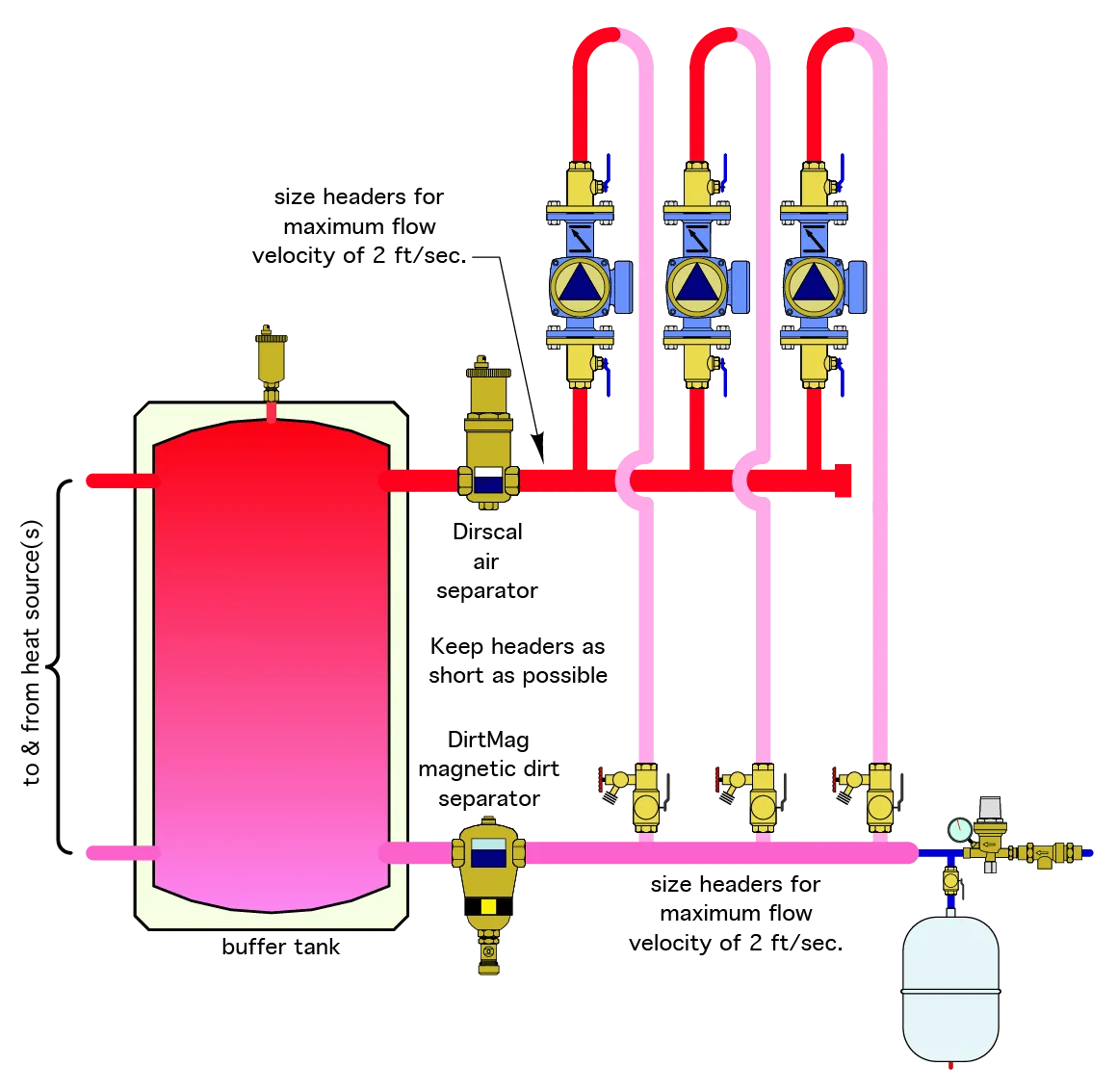

Hydraulic separation can also be achieved when the headers supplying the zone circuits connect to a buffer tank, as shown in figure 2-8.

The flow resistance through the buffer tank is extremely low. The buffer tank, combined with short and generously sized headers, provides a low-flow-resistance common piping path for all the zone circuits, and thus, hydraulic separation is achieved.

Another possibility is to use a pair of closely spaced tees along with the short and generously sized headers to achieve hydraulic separation of the zone circulators, as shown in figure 2-9.

A modern method for achieving hydraulic separation of the zone circuits is to install a hydraulic separator along the short and generously sized headers, as shown in figure 2-10.

The system in Figure 2-10 uses a Caleffi SEP4™ hydraulic separator. In addition to providing hydraulic separation of the circulators, the SEP4 provides microbubble air separation, dirt separation and magnetic particle separation. It eliminates the need to install multiple components for these separation functions, allowing for compact and faster installation.

PURGING PROVISIONS

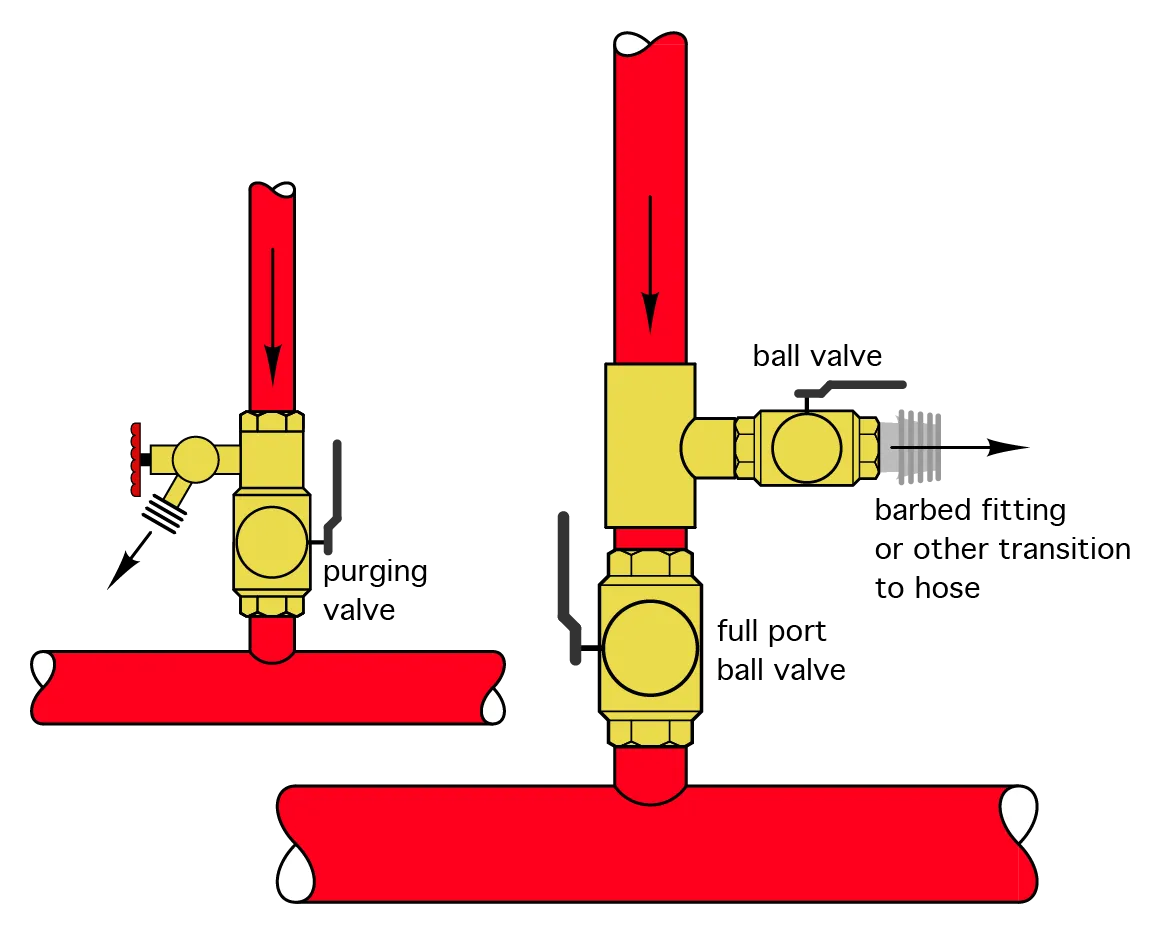

Whenever zoning is used, some means for efficiently filling each circuit and purging it of air should be provided. Figures 2-7 though 2-10 all show purging valves on the return side of each zone circuit. These valves combine an inline ball valve with another "side port" valve that can be connected to a hose. The same functionality can also be provided by installing two separate valves, one in line with the zone circuit and another fitted to the side port of a tee installed just upstream of the inline valve. The latter option is more suitable in systems that use larger piping. Both options are shown in figure 2-11.

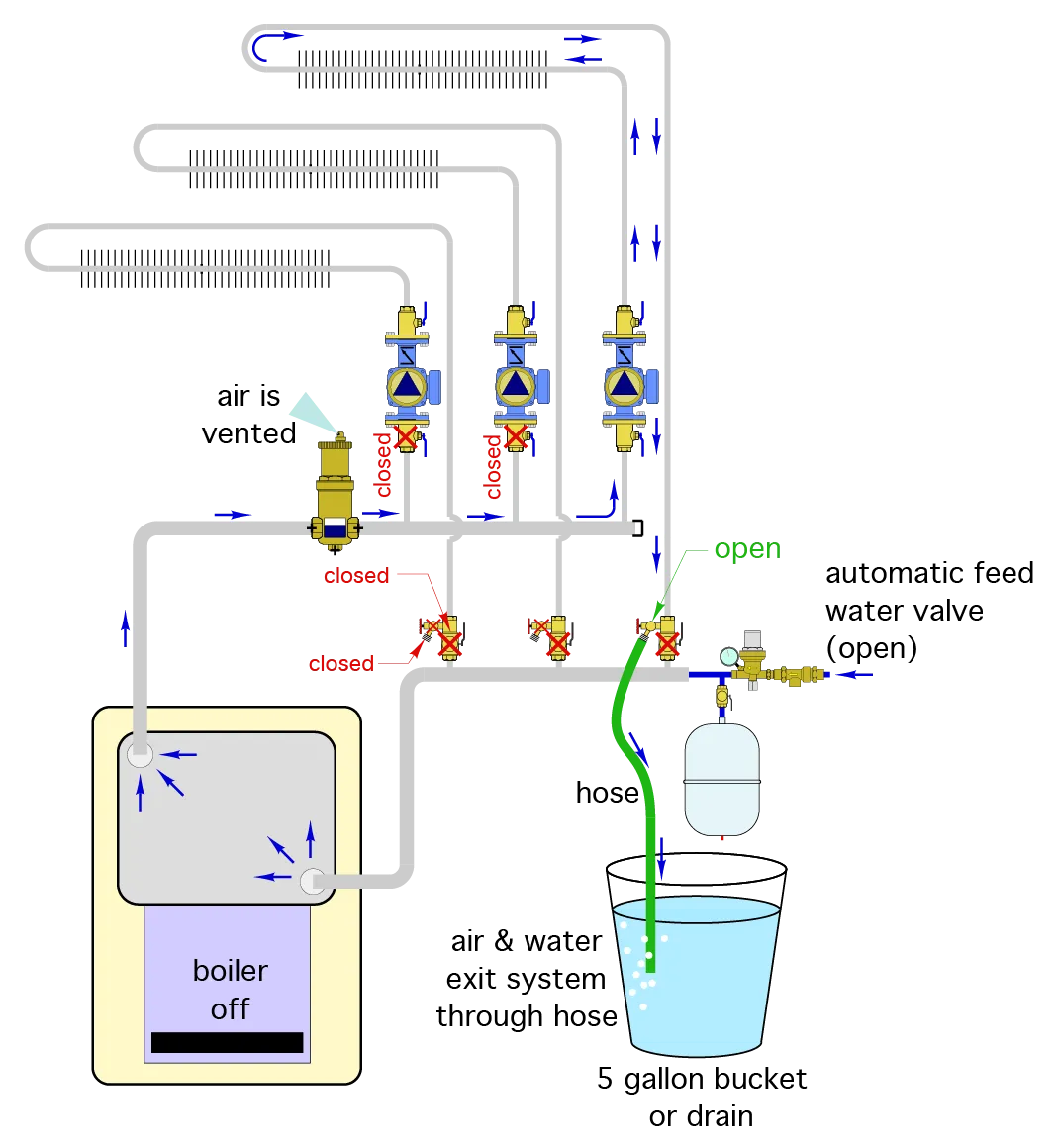

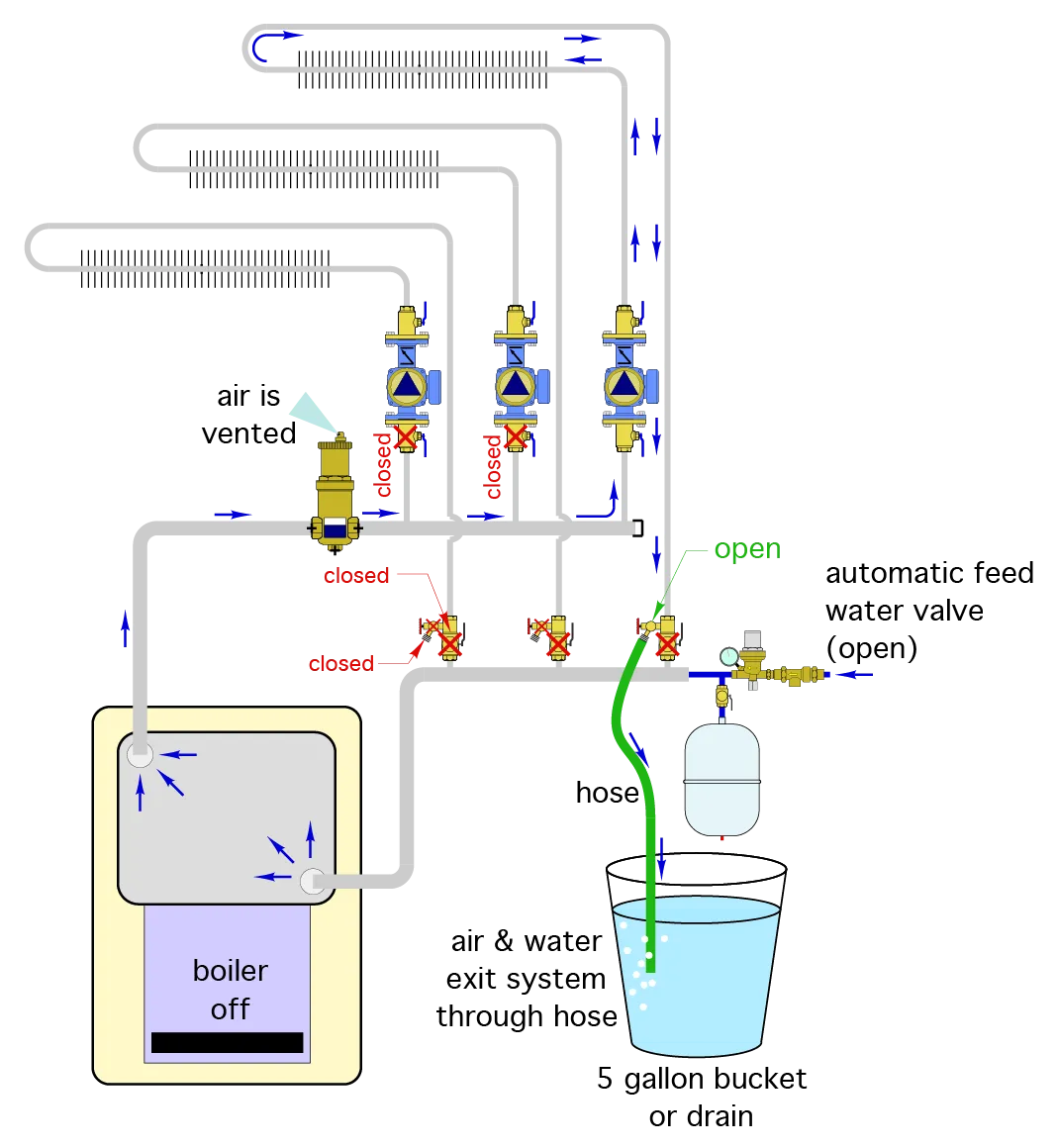

Figure 2-12 shows an efficient method for filling a system with water and purging it of "bulk air."

In this example, a hose is connected to the outlet port of the purge valve on one zone. The inline ball of the purge valve in that circuit is closed, and the outlet valve is opened. The purge valves and isolation flanges on the circulators in the other zones are all closed. Cold water is fed into the system through the opened) pressure-reducing valve. This flow is forced through the boiler, the headers, and the one open circuit. The cold water feed pressure needs to be high enough to create a strong flow rate through the open flow path. Air in the piping path is pushed ahead of the water and eventually exits through the outlet valve on the circuit.

The hose should be held or secured over a bucket or drain. The purging flow should be maintained until the stream leaving the purge valve is free of any visible bubbles. The circuit that was just filled and purged should then be isolated, the hose moved to another purge valve, and the process repeated for the remaining circuits. Purging each zone circuit independently expedites bulk air removal, compared to purging all zone circuits simultaneously.

After all zone circuits are purged of "bulk air," there are still molecules of oxygen, nitrogen and other air gases dissolved in the cold water. A high- efficiency microbubble air separator, such as the Caleffi Discal®, will capture and eject this dissolved air soon after the system is put into operation.

MULTI-ZONE CONTROLLERS FOR ZONE CIRCULATORS

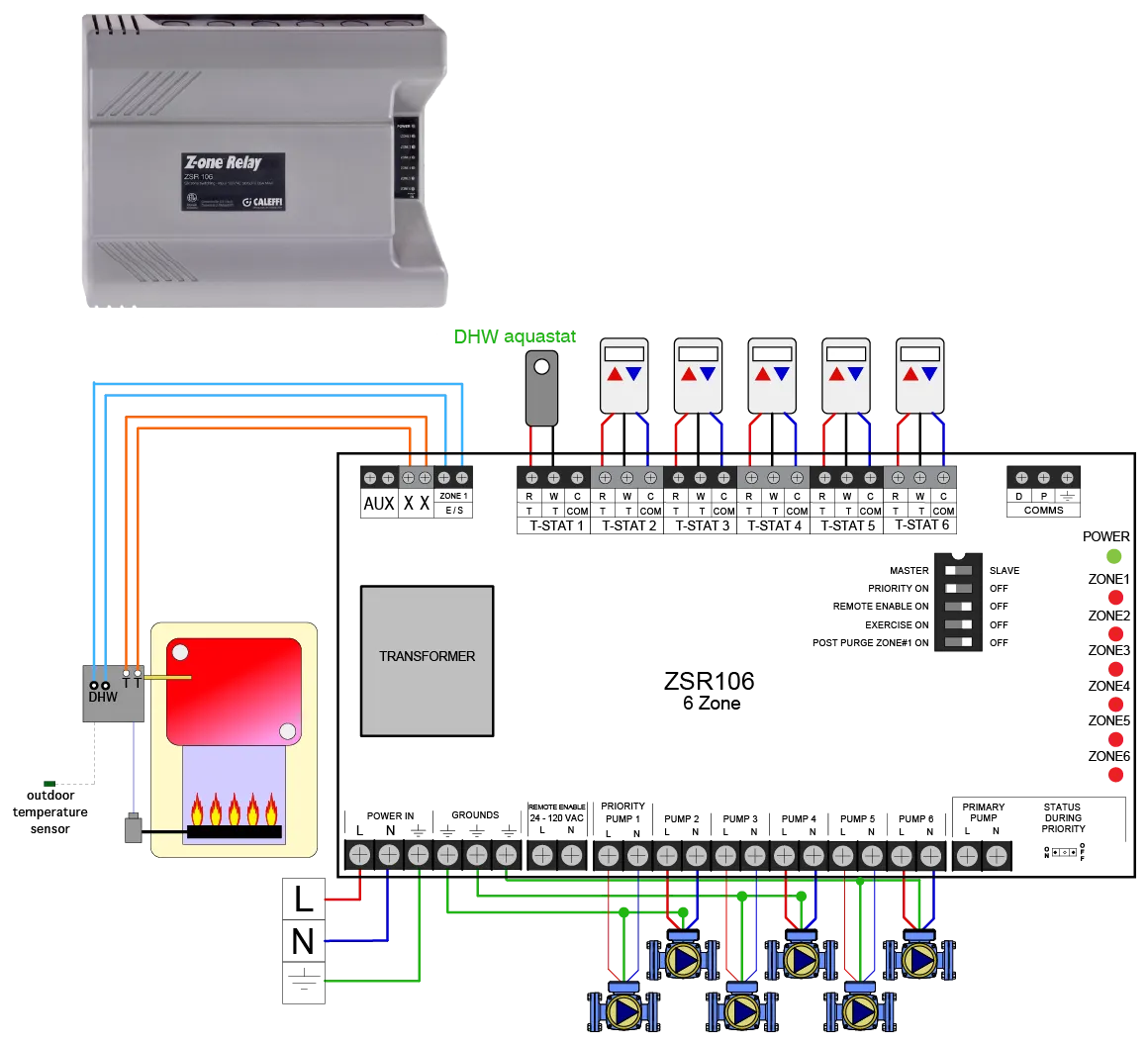

Systems using zone circulators typically use a low-voltage (24) VAC) thermostat in each zone to signal when a line voltage circulator should turn on or off in response to changes in room temperature. These systems also require that the heat source is enabled to operate whenever one or more zone thermostats are calling for heat. Some systems also require one zone to have "priority" over other zones. When the priority zone is active, the other zones are temporarily turned off, at least for some predetermined time interval. In many systems, domestic water heating using an Indirect water heater is treated as the priority zone.

The most convenient, simplest and most cost-effective approach to accomplishing these control functions is by using a Multi-Zone Pump Control. Figure 2-13 shows an example of the Caleffi ZSR106 Multi- Zone Pump Control.

The Caleffi ZSR106 Multi-Zone Pump Control provides wire "landing" terminals for up to six zone thermostats. When a heating call is received from a specific thermostat, the relay center turns on the associated zone circulator and signals the heat source to operate. Similar multi-zone pump controls are available for systems with motorized zone valves. These are discussed in the next section. See idronics 14 for more information on Caleffi multi-zone controllers.