The purpose of any heating system is to provide comfort in all areas of a building throughout the heating season. Likewise, cooling systems are expected to establish and maintain comfortable interior conditions based on air temperature and humidity.

Accomplishing these objectives requires systems that can adapt to the lifestyle and activities of the building occupants, as well as constantly changing thermal conditions inside and outside of a building.

Imagine a building in which all rooms have the same floor area and the same wall height. Someone not familiar with heating systems might assume that, because all the rooms are the same size, they require the same rate of heat input at all times. Although that assumption is reasonable, it doesn’t account for differences in the thermal characteristics of the rooms. Some rooms may have only one exposed wall, while other rooms might have two or three exposed walls. Some rooms might have a large window area, while other rooms have no windows. The air leakage, and potential for sunlight to enter through windows, could also vary from one room to another.

Beyond these differences are conditions imposed by occupants. One person may prefer to sleep in a room maintained at 65ºF, while another feels chilled if their bedroom is anything less than 72ºF. Someone might prefer a living room temperature of 70ºF while relaxed and reading, but they may also expect the temperature in an exercise room to be 62ºF during a workout.

The combination of room thermal characteristics, weather conditions, inside activities, internal heat gains from equipment and lights, and occupant expectations presents a complex and dynamic challenge for building heating and cooling systems as they attempt to maintain the desired comfort level.

One technique that helps heating and cooling systems adapt to changing conditions and occupant expectations is dividing the system into multiple zones.

A zone is any area of a building for which indoor air temperature is regulated by a thermostat or other temperature sensing control device.

A zone can be as small as a single room or as large as an entire building. The number of zones in a building can range from one to as many as the number of rooms in the building. The latter scenario is called room-by-room zoning.

The greater the number of zones, the more flexibility the occupants have in selecting comfort levels well suited to the activities and other imposed conditions occurring within the building. However, the quality and performance of a zoned heating or cooling system is not determined solely by the number of zones it has.

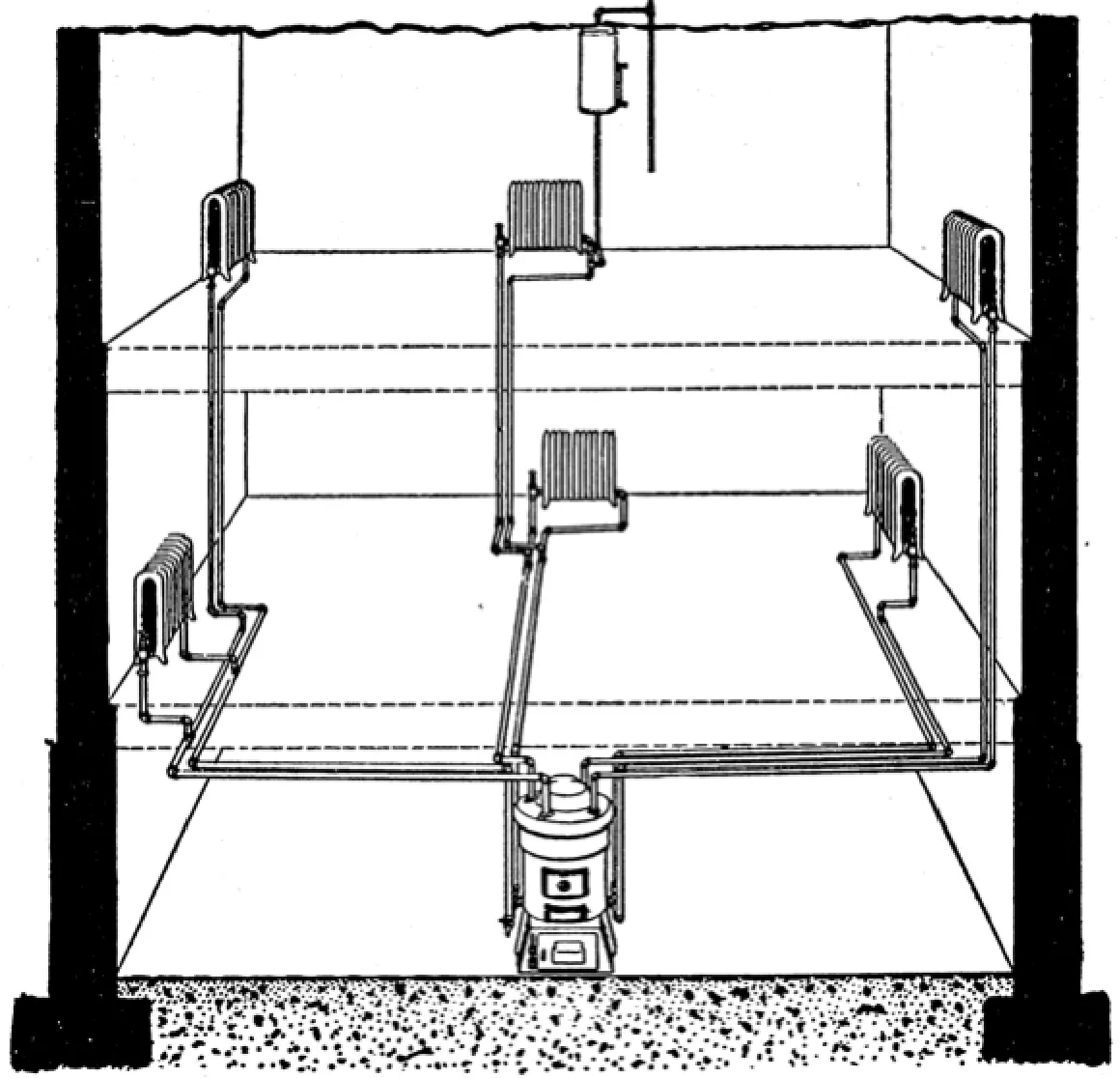

Zoning has been used in hydronic heating and cooling systems for decades. Even early systems without circulators or electrical controls allowed for zoning through use of manually operated valves at each radiator. By adjusting these valves, it was possible to change the flow rates, and thus the heat outputs, from each radiator.

Although these early systems were rudimentary compared to what is possible using modern hydronics technology, they recognized and addressed the need for varying the rate of heat delivery to different areas of a building to accommodate changing conditions and occupant preferences.

WHY IS ZONING BENEFICIAL?

The two most-recognized benefits of zoning are:

1. Allowing occupants to remain comfortable in different areas of a building while accommodating individual or group comfort preferences, activity levels, and continuously varying sources of internal heat generation or other conditions that affect heating or cooling loads.

2. Allowing different internal spaces to be set at comfort levels that, at times, reduce the energy input to heating or cooling systems, and thus lower operating costs. Setting a heating thermostat in a particular zone to a lower temperature during an unoccupied period is an example.

Other benefits include enhancing human productivity in commercial buildings, improved sleeping comfort, and reduced pumping energy in hydronic systems.

ZONE PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS:

When planning a hydronic heating or cooling system, it is important to consider how best to divide the building space into zones, as well as how best to control heat output or cooling delivery within each zone. The goal is to achieve the previously stated benefits without creating systems that are overly complex, expensive or difficult to control. There is no "standard" approach for zoning design. Every project has nuances that need to be considered. Fortunately, modern hydronics technology provides the flexibility to accommodate a wide range of possibilities. Given the extensive amount of hardware now available for hydronic zoning, one might assume that the more zones a system has, the better that system was designed. This isn't necessarily true. Just because it is easy to design a system in which every room is controlled as a separate zone does not mean it's always the wisest choice. "Over- zoning" can add expense without returning tangible benefits. It can also lead to issues such as short cycling of the system's heating or cooling source, reduced efficiency and increased maintenance costs. The following considerations all play a part in planning a zoned system.

THE EFFECT OF THERMAL MASS

People sometimes assume that a zoned heating system should be able to reduce the temperature within a given space as soon as the thermostat setting is lowered, or increase that temperature as soon as a thermostat setting is increased. This is not possible because of the thermal mass of the building materials and heating system components. Thermal mass is the ability of materials to store heat. All materials have some amount of thermal mass, depending on their specific heat and density. Concrete, masonry and drywall have higher thermal mass per unit of volume compared to materials such as wood, plastic, insulation or fabric.

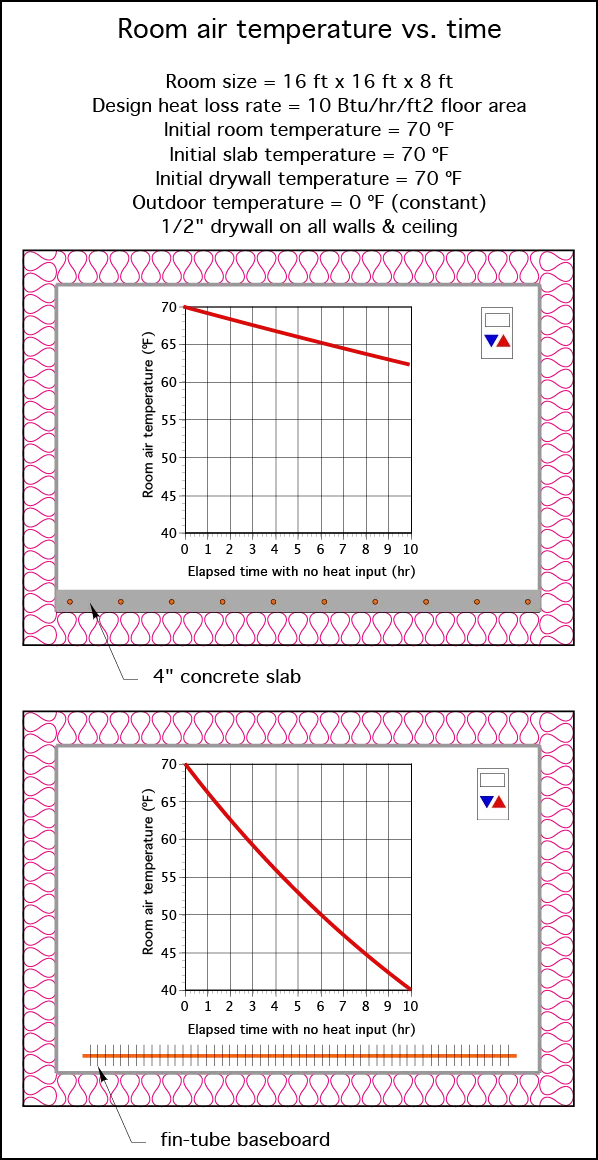

The greater the total thermal mass within a given building space, the slower the air temperature will change when the thermostat setting is increased or decreased. This is illustrated in figure 1-5, which charts the decrease in room temperature over several hours, assuming there is no heat input from the heating system.

The upper curve is for a room with a 4-inch-thick concrete slab. With no heat input from the heating system, all heat lost from the room is replaced from the thermal mass of the slab and the drywall on the walls and ceiling, all of

which had an initial temperature of 70ºF. Over the course of 10 hours, during which the outdoor temperature remains at 0ºF, the room temperature decreases from 70ºF to approximately 62.5ºF.

The lower curve also shows how the air temperature in the room decreases, but in this case, the room doesn't have the concrete floor slab. All heat lost from the room is replaced from the thermal mass of the drywall and stationary water within 16 feet of the residential fin-tube baseboard. Over the same 10-hour period, and with the same outdoor conditions (i.e., O°F outdoor temperature), the room's air temperature would drop to about 40°F.

It's important to remember that most thermostats are simply temperature-operated switches. Lowering the thermostat setting several degrees simply opens an electrical circuit running through the thermostat that prevents further heat input from the heat emitters in that space.

Consider the room represented by the assumptions and graph in figure 1-5. Assume that the occupants turn the thermostat setting from 70°F to 60°F at bedtime (e.g., when the elapsed time shown in figure 1-5 begins).

The temperature in the room containing the concrete floor slab doesn't drop to 60°F, even after 10 hours. However, the room without the floor slab has much lower thermal mass. Its temperature drops to the 60°F setpoint in less than three hours. At that point, the thermostat would turn the heating system on to prevent further temperature drop.

Because the room with the lower thermal mass would undergo more elapsed time at an interior temperature of 60°F, and because the rate of heat loss from the room decreases at lower interior temperatures, the energy savings associated with the thermostat setback would be greater compared to that of the room with the floor slab.

The potential energy savings associated with thermostat setbacks are highly dependent on the heat loss and thermal mass characteristics of the space in which the thermostat is located. Spaces having well-insulated and tightly sealed thermal envelopes, as well as high thermal mass construction, will experience minimal energy savings from daily thermostat setbacks.

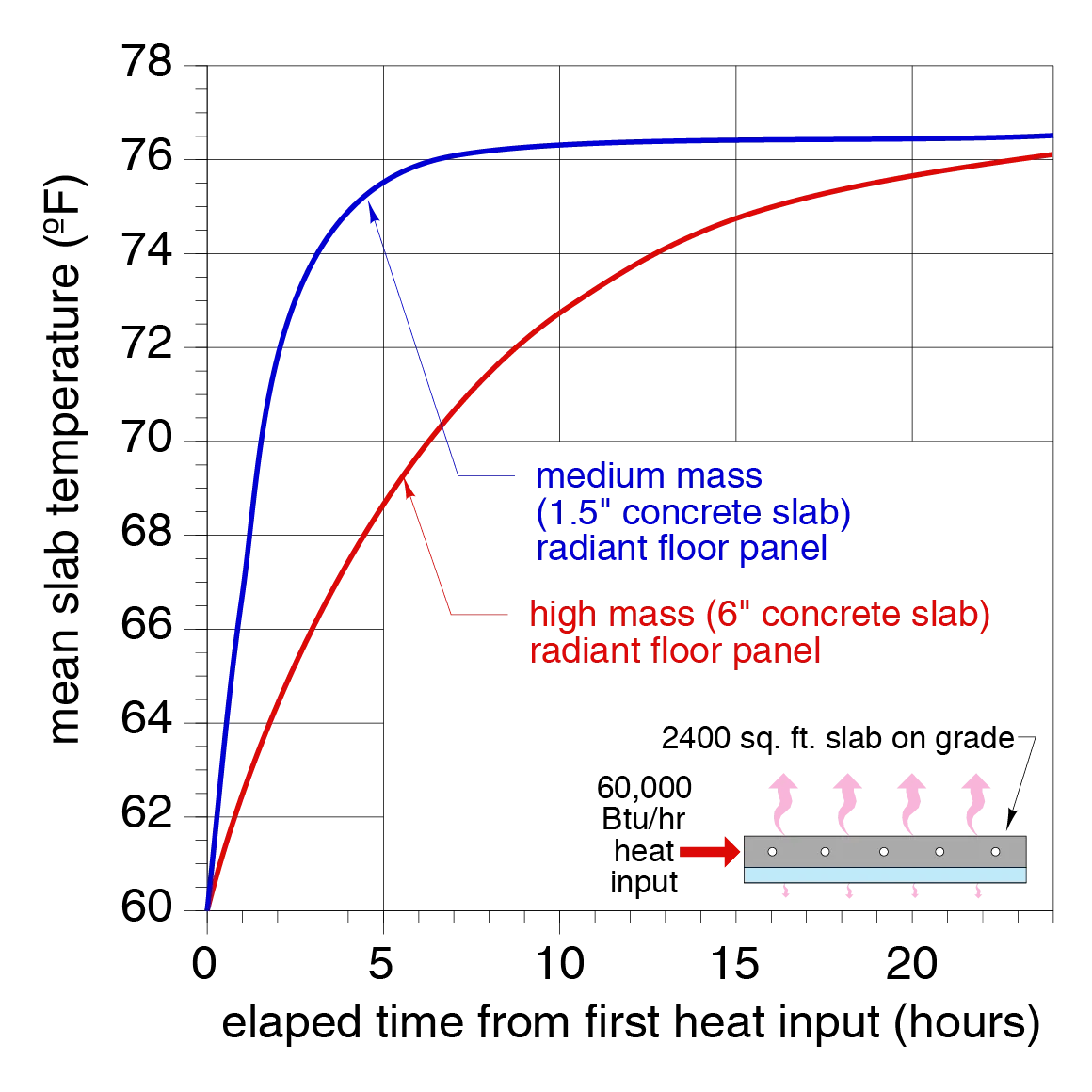

Thermal mass also affects the rate at which a space at some initial temperature can be warmed to a higher temperature. Spaces with high thermal mass heat emitters, such as a heated floor slab, warm significantly slower compared to spaces with low thermal mass heat emitters.

Figure 1-7 shows the latter effect by charting the time required for a 2,400-square-foot floor slab to be warmed from an initial temperature of 60°F, while absorbing heat at a constant rate of 60,000 Btu/hr.

The 1.5-inch-thick "thin slab" approaches its steady state condition after about 8 hours of heat input. However, the 6-inch-thick slab is still increasing temperature after 24 hours of steady heat input.

If rooms with significantly different thermal mass are combined on the same zone (e.g., controlled from the same thermostat), their temperature responses can be very different. The space with low thermal mass will reach the desired temperature much quicker than the space with high thermal mass. It's likely that this difference in response will lead to complaints, especially if thermostat setbacks or other frequent thermostat setting changes occur.

When two or more rooms are being considered to operate as a single zone, it's important that they have similar thermal mass in both their interior materials as well as their heat emitters.

HEAT TRANSFER BETWEEN ZONES

In an ideal scenario, each zone within a building would act as if it were an isolated "compartment," completely separated from other zones in the building. In such a scenario, it would be possible to set the desired air temperature of one zone at 70°F and the desired temperature of an adjacent zone at 60°F. The heat emitter(s) within each zone would release heat at the rates needed to maintain those set temperatures. Occupants would also be able to walk between these zones without disturbing those temperatures.

In reality, such a scenario doesn't exist. In many buildings, the separation between adjacent zones is an uninsulated partition. Interior doorways from rooms on different zones often lead to common spaces such as hallways. Even in situations where adjacent zones are separated by closed interior doors, those doors are typically not insulated and offer minimal resistance to heat transfer.

The relatively weak thermal separation of adjacent interior zones can result in significant inter-zone heat transfer. A room maintained at 70°F will transfer heat through an uninsulated interior partition or open doorway to an adjoining room that's at a lower temperature. This effect is especially pronounced in buildings with well-insulated thermal envelopes.

Inter-zone heat transfer might be viewed as beneficial because it tends to equalize interior temperatures between spaces where heat emitter outputs are not well matched to loads, or where unanticipated internal heat gains occur. However, inter-zone heat transfer makes it difficult to maintain temperature differences of more than about 5°F between rooms in well-insulated buildings, even when the interior doors in those rooms are kept shut. This effect partially defeats one of the often-intended goals of zoning.

When it's desirable to maintain higher temperature differences between adjacent zones, interior partitions need to be insulated. Interior doors between those zones should also provide a relatively tight seal against interior air flows and remain closed. Although this is all possible, it is not commonly implemented in modern residential or commercial construction.

INTERNAL HEAT GAINS

All buildings experience unscheduled heat input from sources other than their heating system. Building spaces with minimal windows, low occupancy and minimal if any electrical load, usually have low internal heat gain. Spaces with large window areas on east, south or west walls, or skylights can experience large solar heat gains based on the time of day and weather conditions. Spaces where people gather, or where lots of electrically powered equipment operates, can also experience high internal heat gains.

These gains can significantly affect thermal comfort, and as such should be considered when planning zones. In general, building spaces with the potential for high internal heat gains should not be on the same zone as spaces with minimal internal heat gains.

An example would be a building with significant window area on the east, south or west sides. As the sun moves across the sky on a clear day, rooms with east-facing glass will warm first due to morning sunlight. Next to warm will be rooms with south-facing windows. During the afternoon, rooms with west-facing glass will experience solar heat gains. During this same time, rooms with north-facing glass will experience minimal if any solar heat gain. Setting these different rooms up as separate zones would help in maintaining comfort by allowing heat input to vary based

on solar heat gains. Equally important would be using heat emitters with low thermal mass that can quickly adjust heat output to compensate for the heat gains.

Formula 1-1:

Internal heat gains from occupants depend on the number

of people present and their activity level. A sedentary adult

will typically generate 350 to 400 Btu/hr of metabolic heat

output. The same person engaged in a strenuous or highly

athletic activity could generate close to 2,000 Btu/hr.

Internal heat gain from electrically operated devices within

a space is relatively easy to estimate once the wattage of

the device(s) is determined. Use formula 1-1 to convert

watts to Btu/hr.

OCCUPANCY SCHEDULE

Zoning allows for reduced temperatures in spaces when they are unoccupied, resulting in reduced heat loss. Leveraging this potential benefit requires planning that separates spaces that can operate at reduced temperatures from spaces where temperature setback is unlikely or undesired.

Bedrooms are often zoned separately from spaces that are occupied during daytime hours. It's also good to put bathrooms and bedrooms on separate zones. This allows the bathrooms to be brought to a comfortable temperature for morning showers, while bedrooms remain at lower temperatures.

Rooms that are only occasionally occupied are also good candidates for separate zoning. Examples include a guest room, workshop area or a recreation room. When such areas are zoned separately, it’s important to consider the time required to bring them from a reduced temperature

to the desired comfort level. Areas maintained 10ºF or more below normal occupancy temperature, and having high thermal mass, can take several hours to warm back to the desired occupancy temperature. If this is unacceptable, those spaces should be equipped with low thermal mass heat emitters.

Areas with significantly different occupancy schedules should not be on the same zone.

ROOM-BY-ROOM ZONING There are several ways to make every room in a building a separate zone. In some situations, this can be done at minimal additional cost. In other circumstances, it can add thousands of dollars to the installed cost of the system.

Given the zone planning considerations just discussed, room-by-room zoning provides the greatest flexibility for factors such as differences in thermal mass, internal heat gain or occupancy schedules.

The decision to use room-by-room zoning depends on several factors:

1. The piping method and materials required to allow flow adjustments through the heat emitter(s) in each room.

2. Any added cost compared to combining some rooms onto a single zone.

3. The likelihood that the temperature in different rooms will need to be changed on a regular basis.

4. The likelihood of significantly different internal heat gains from one room to another.

Piping and control methods for room-by-room zoning are necessarily more complex than those needed for minimally zoned systems. These methods will be discussed in later sections.

The cost to implement room-by-room zoning depends on the hardware used. Electronic thermostats, along with the associated low voltage wiring and electrically operated valves, often cost more than using non-electric thermostatic valves. However, modern thermostats offer more features, such as WiFi accessibility, setback schedules and the ability to "learn" occupant preferences over time.

Keeping different rooms in a building at different but consistent temperatures is possible without the need for room-by-room zoning. It can be done using techniques such as flow adjustment, mixing devices that create multiple supply water temperatures, or by varying tube spacing within site-built radiant panels. These techniques don't require a separate thermostat (or other temperature- sensing control device) in each room.

Room-by-room zoning is ideal when there's a need to make recurring changes in the temperature of some rooms with minimal impact on the temperature in other rooms. It's well-suited to situations where occupants want the possibility of setting different temperatures for sleeping rooms, bathrooms, exercise areas, rooms for growing certain types of plants, or rooms for people with medical conditions that favor warmer temperatures. It's also a good choice in situations where rooms have widely varying potential for solar or other internal heat gains.

Not all buildings need room-by-room zoning. Buildings with large open spaces or passages between adjoining rooms tend to defeat the purpose of room-by-room zoning due to ease of natural heat flow between spaces. This is especially true if the thermal envelope surrounding these adjoining spaces presents high resistance to heat loss. While it's certainly possible to install expensive thermostats in every room of a large house, and to install wiring from all those thermostats to associated controls in the mechanical room, doing so can add significant cost without producing significant performance benefits.

The sections that follow describe several approaches to creating zoned hydronic systems. They vary based on the hardware and control methods used. When properly designed and installed, all these methods can provide accurate control of heat delivery or cooling effect when and where it's needed within a building.

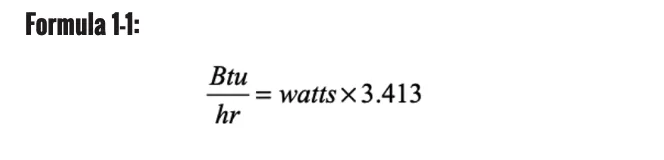

Formula 1-1:

Internal heat gains from occupants depend on the number of people present and their activity level. A sedentary adult will typically generate 350 to 400 Btu/hr of metabolic heat output. The same person engaged in a strenuous or highly athletic activity could generate close to 2,000 Btu/hr.

Internal heat gain from electrically operated devices within a space is relatively easy to estimate once the wattage of the device(s) is determined. Use formula 1-1 to convert watts to Btu/hr.

<$$\frac{Btu}{hr} = watts \times 3.413$$>