The preceding section described valves that use electric motors to open and close the valve. Although such valves are common in residential and commercial zoning applications, they are not the only type of valve that can be used for zoning. Another category of control valves is based on thermostatic (rather than motorized) actuators. These actuators use heat to produce the motion that moves the valve's shaft. The source of the heat varies depending on the application.

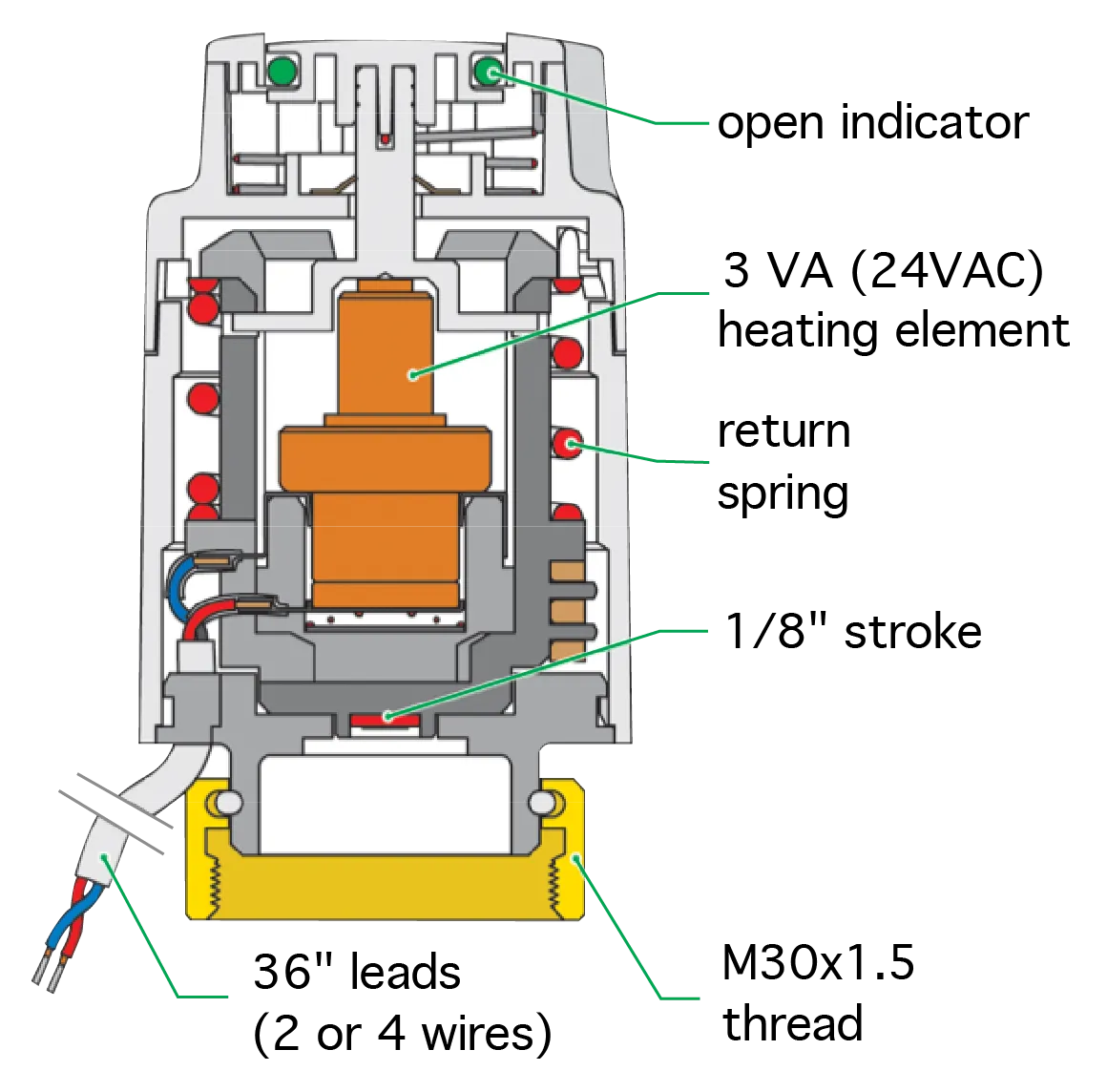

In some applications, the heat needed to operate the valve comes from an electrical resistor inside the valve's actuator. This type of actuator is more specifically called a thermo-electric actuator. A cross section of the Caleffi 6564 thermo-electric TwisTop™ actuator attached to a Caleffi 6762 2-way valve body is shown in figure 4-1.

When an electrical current supplied from a 24 VAC source passes through the resistor, it heats a small piston/cylinder assembly (2) containing a specially formulated wax. Heating causes the wax to expand, which moves the piston several millimeters. That motion is transferred to the valve's shaft to lift the disc (1) off the valve seat. When electrical power is removed, the wax shrinks back to its original volume. A spring assists in closing the valve, holding it closed to its rated close-off pressure.

Caleffi 6563 thermo-electric actuators are available with an isolated end switch that allows them to be wired the same way as a four-wire motorized zone valve. A small "pop-up" disc at the top of the actuator shows when the actuator shaft is fully extended and the valve is open. These actuators also have a TwisTop feature that allows the actuator to be manually operated to open the valve during a power outage, during system commissioning or whenever needed.

Thermo-electric actuators have slower response characteristics relative to motorized valve actuators. The 6563 actuator requires 120-180 seconds to fully open. The upper end of this time range applies to situations where the actuator is surrounded by cold air prior to being powered. Closing time also varies between 120 and 180 seconds, depending on the temperature of the actuator when power is removed and the surrounding air temperature. These longer opening and closing times are typically not an issue when the valves are used for zoning. They also reduce the potential for water hammer as the valve disc closes over its seat. Thermo-electric actuators are completely silent as they open and close, making them ideal for situations where zone valves need to be installed in noise-sensitive areas.

Caleffi 6563 thermo-electric actuators have an initial power draw of about six watts but stabilize to a continuous power draw of about three watts when fully open. Caleffi 6762 valves fitted with 6365 thermo-electric actuators have a Cv rating of 4.0, and a close-off pressure rating of 20 psi. Caleffi 6765 valves fitted with the same actuator have a Cv rating of 5.6, and a close-off pressure rating of 35 psi.

Thermo-electric actuators should not be used in systems where the zone valve is located within an enclosed heat emitter, such as a fin-tube baseboard housing or the cabinet of a wall convector. The internal temperature of such emitters can, under some circumstances, slow or prevent full closure of the valve when power is removed.

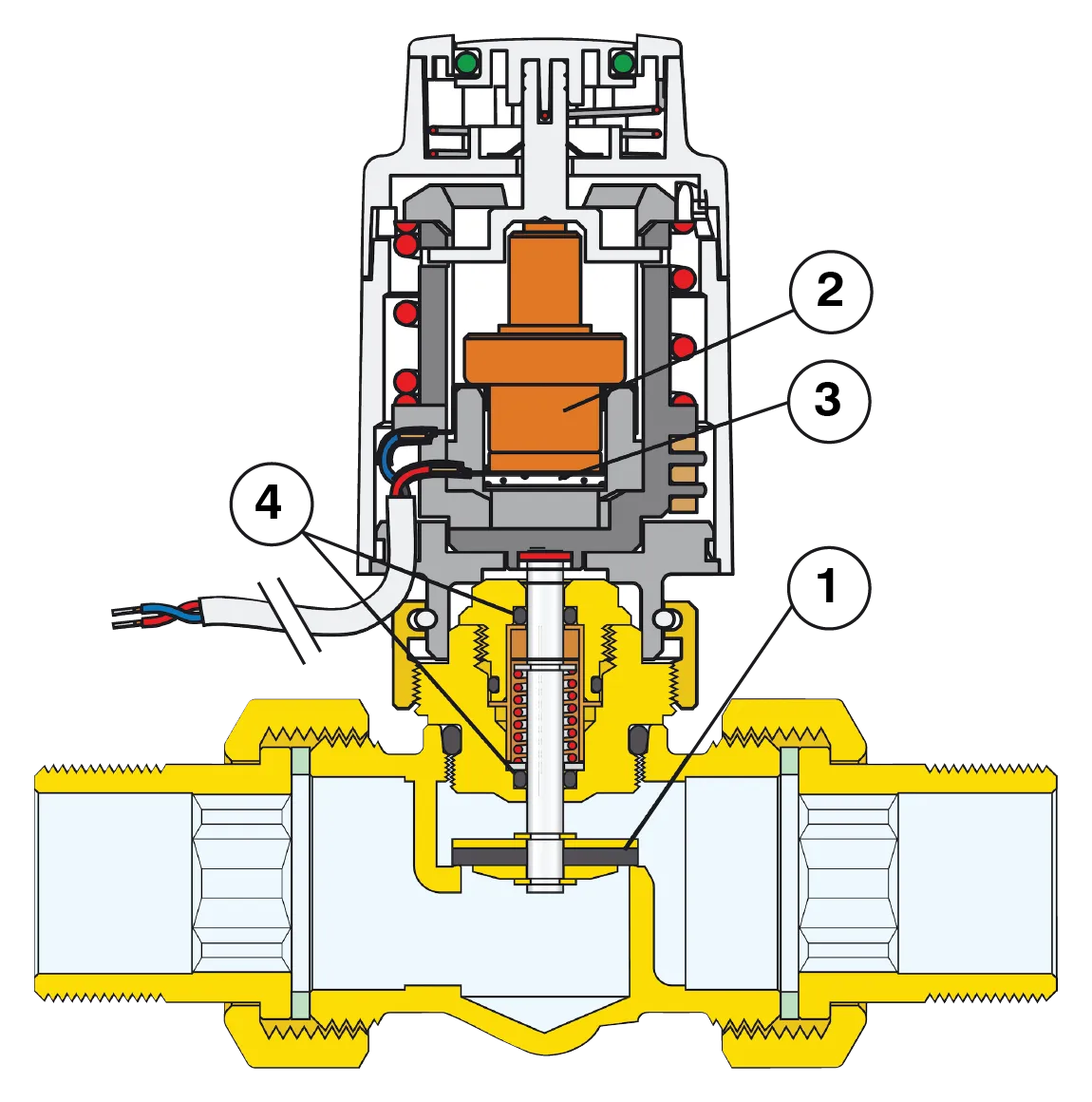

These Caleffi thermo-electric zone valves are available in nominal pipe sizes from 1/2-inch to 1-inch. Connection options include press copper, cold expansion PEX and solder copper, as shown in figure 4-2.

Thermo-electric valve actuators can also be combined with valved manifolds to create multi- zone systems. Functionally, this approach is equivalent to using several individual valves, each with its own thermo-electric actuator.

However, all valving hardware is now integrated into a single preassembled component. This "homerun" approach also makes use of flexible PEX, PERT or PEX-AL-PEX tubing, rather than traditional rigid piping, to supply each of the system's heat emitters.

Figure 4-3 shows an example of a circuit valve built into the return manifold. These valves are opened and closed with a linear (versus rotational) movement of their shaft. The valves are also spring loaded. The spring force maintains the valve in its fully open position. A manifold valve can be manually adjusted by rotating the plastic knob that covers each valve stem.

The operation of manifold valves can be automated by adding a Caleffi 6563 thermo-electric actuator to each valve, as shown in figure 4-4. The actuator simply screws onto the valve, pushing the valve's stem to the closed position as it is mounted.

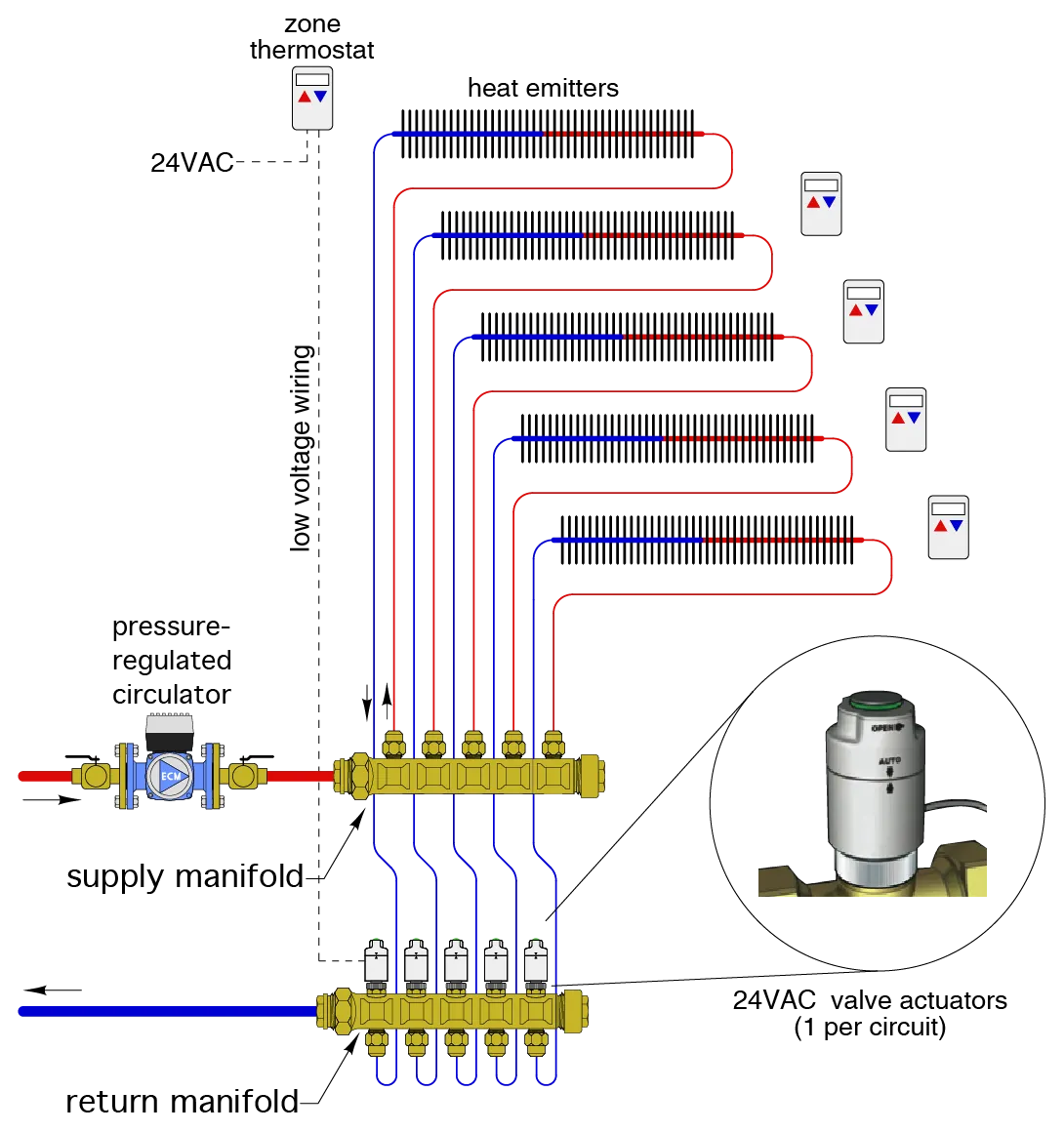

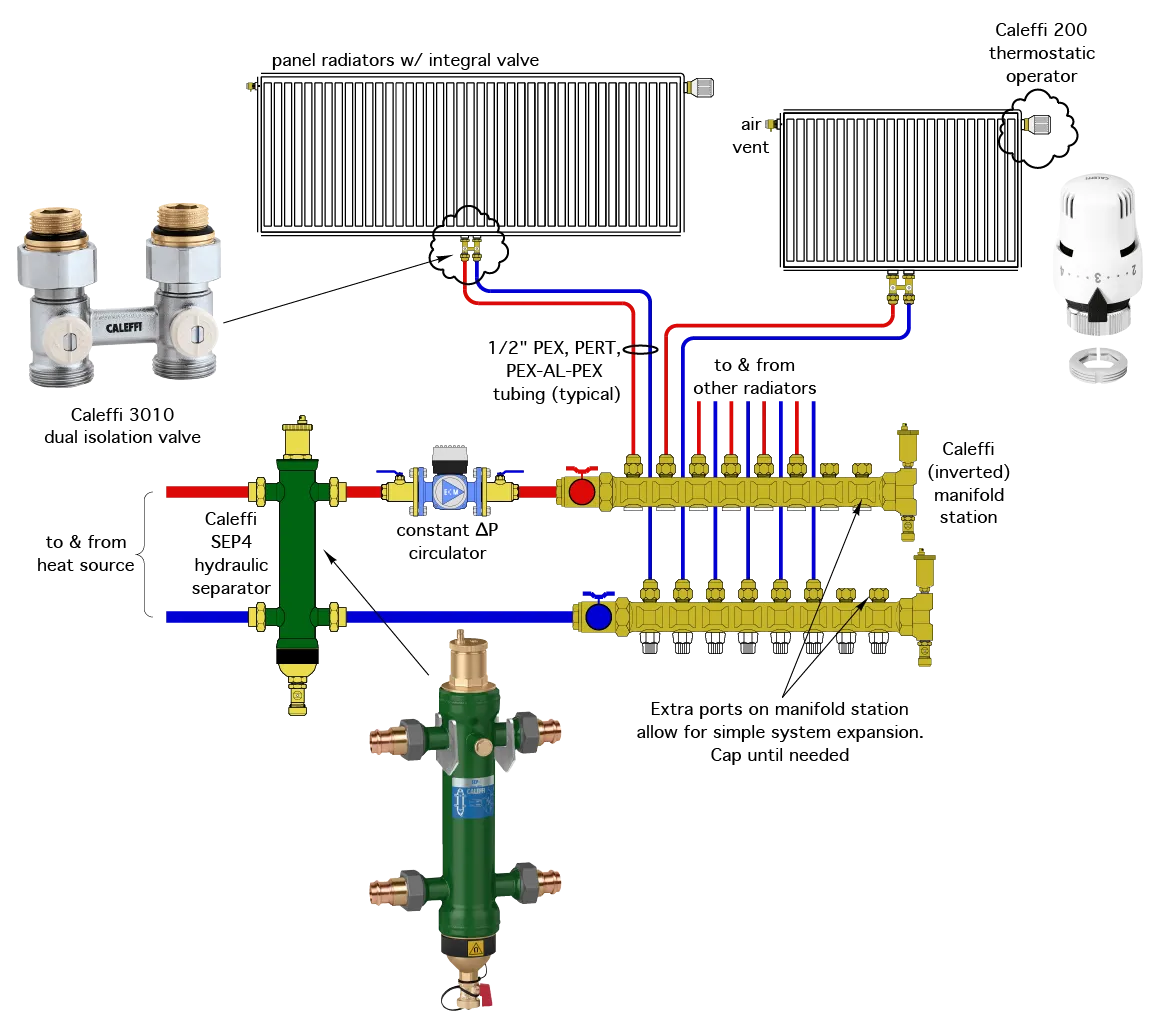

An example of a homerun distribution subsystem using a manifold station with valve actuators is shown in figure 4-5.

In a homerun distribution system, each heat emitter is connected to the supply and return manifolds using separate runs of small diameter PEX, PERT or PEX-AL-PEX tubing. Each heat emitter, along with its associated thermostat, constitutes an independent zone. When any thermostat calls for heat, 24 VAC is applied to the associated thermo-electric valve actuator. After a short time, the actuator retracts its shaft and the spring-loaded manifold valve opens, allowing flow through its associated heat emitter.

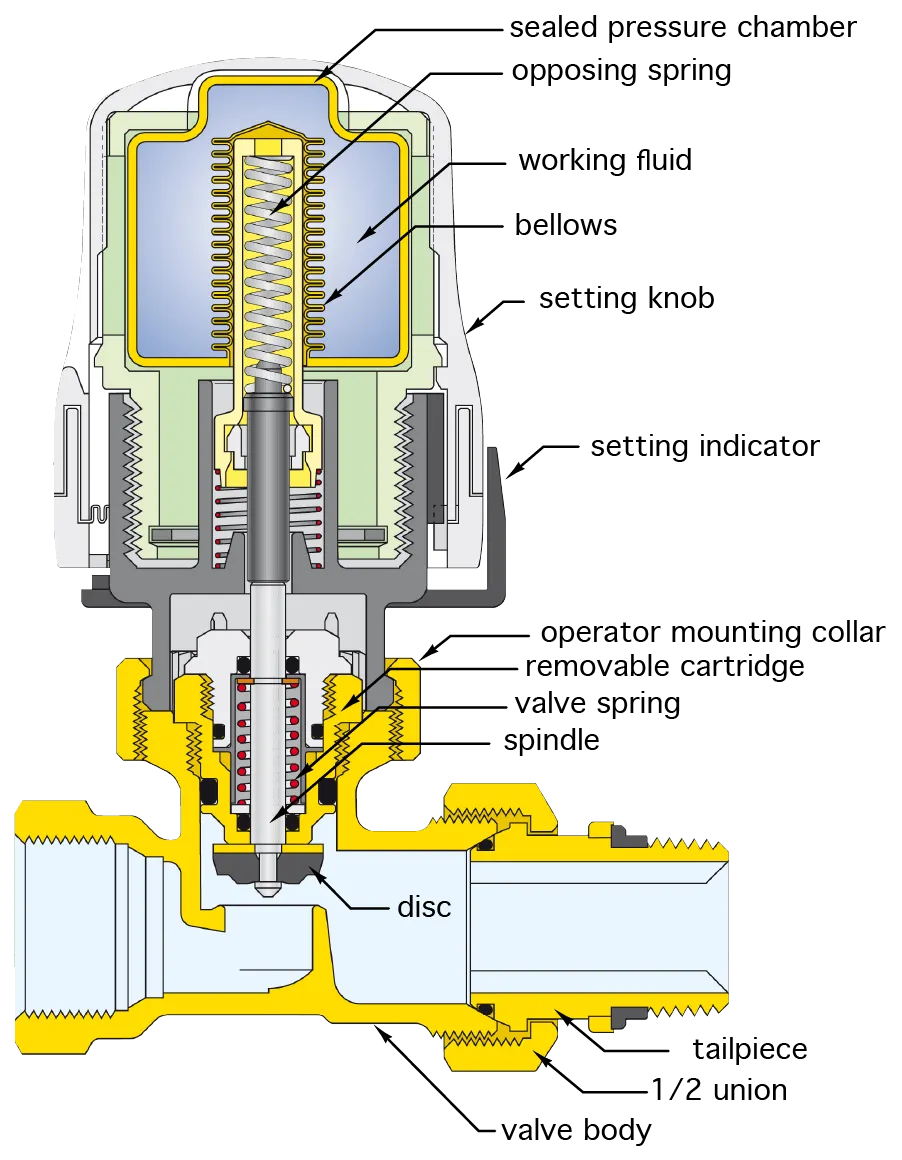

Several types of valves can also be combined with non-electric thermostatic operators. The most common application for these operators is in combination with small spring-loaded valves that control flow through heat emitters, such as panel radiators or fin-tube baseboard. Figure 4-6 shows an example of how a non-electric thermostatic operator is matched with a radiator valve.

The thermostatic operator screws onto the valve's bonnet. When mounted, it pushes the valve's stem down, closing the valve. From this initial status, the position of the valve's stem is regulated based on the setting of the operator's knob and the surrounding air temperature. This action is created by the internal design of the operator, as shown in figure 4-7.

The thermostatic operator contains a bellows filled with a working fluid that expands and contracts when its temperature changes. This movement is transferred to the valve spindle and ultimately to the valve's disc.

When the air temperature surrounding the thermostatic operator increases, the valve stem is pushed down, moving the disc closer to its seat and reducing flow through the valve. When the air temperature decreases, the valve's stem rises, allowing the spring-loaded valve shaft to rise, increasing flow through the valve. This "feedback" between air temperature changes and flow through the valve can provide stable interior temperature control. It's a technique that has been used in tens of millions of hydronic heating systems around the world for many decades.

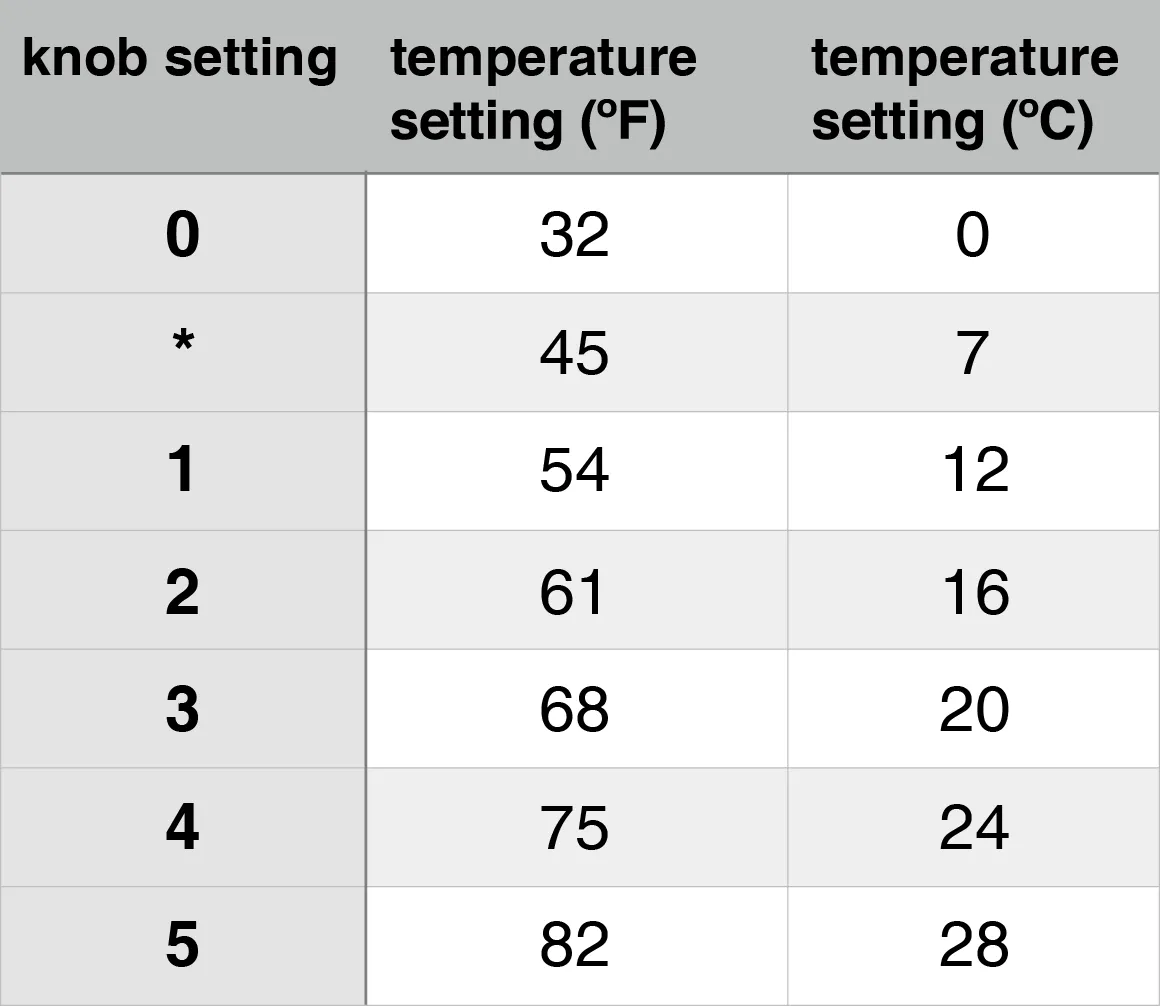

The "comfort setting" of a thermostatic valve operator is adjusted by rotating the outer knob. Rather than temperature settings, the knob has numbers from 1 to 5 as relative indicators of comfort. This encourages occupants not to associate comfort with a specific room temperature. The correlation between the numbers on the knob of the Caleffi 200 thermostatic operator and the corresponding room temperature setting are shown in figure 4-8.

The setting of (*) provides freeze protection in unoccupied spaces.

Unlike thermo-electric actuators or motorized zone valves which function as fully open or fully closed, non-electric thermostatic operators can modulate the flow through a heat emitter over a wide range. This ability to continually fine-tune flow through each heat emitter helps minimize room temperature variations.

Radiator valves equipped with thermostatic operators are typically mounted close to or directly to the inlet port of a heat emitter.

The flow direction through the valve is indicated by an arrow on the valve body. It's important that flow passes upward through the valve's seat and against the valve's disc. Piping the valve in reverse can lead to chatter, water hammer or other undesirable sounds when the valve's disc is close to its seat.

Care must be taken not to mount the operator so that warm air rising from the heat emitter goes directly over the operator. This will cause the operator to close the valve very shortly after hot water begins flowing through the heat emitter. Keeping the long axis of the operator in a horizontal position and pointing away from the heat emitter is ideal.

Thermostatic operators can also be mounted to a "straight" pattern.

They are also available as an "angle" pattern valve. The latter is shown in figure 4-10b, where the valve body provides a 90-degree angle between the valve's inlet and outlet ports.

Thermostatic valve operators can also be fitted directly to panel radiators that have integral valves, as shown in figure 4-11.

The thermostatic operator is simply screwed onto the threaded portion of the integral valve. However, it's important to verify that the radiator valve stem projection is compatible with the thermostatic operator.

In some cases, it may be necessary to use an adapter between the valve body and thermostatic operator, as shown in figure 4-12.

Radiators with integral valves place the thermostat operator at a convenient height for adjustment, as shown in figure 4-13.

When multiple panel radiators with integral valves are served by a homerun distribution system, as shown in figure 4-14, each radiator can be independently controlled, and thus, becomes a zone.

The concept shown in figure 4-14 is simple but elegant. Each panel radiator functions as an independent zone, both hydraulically and thermally.

Flexible 1/2-inch size PEX, PERT or PEX-AL-PEX tubing is ideal for connecting panel radiators to the manifold station. It's easily routed along floor framing or through wall cavities, making this approach well suited to retrofit applications.

The transition between the tubing and the radiator is made using a Caleffi 3010 dual isolation valve. This component contains two independent ball valves that can be opened or closed using a screwdriver. When these ball valves are closed, the panel radiator is isolated from the remainder of the system, and can be removed, if necessary, without affecting the other radiators in the system.

Figure 4-15 shows a closeup of the area where the 1/2-inch PEX-AL-PEX tubing supplying a "compact" style panel radiator rises through the floor and attaches to the Caleffi 3010 dual isolation valve.

For this style of panel radiator, the holes through the floor should be drilled 2 inches on-center, and slightly larger than the tubing to allow for expansion and contraction without noise or stress. When several radiators of the same style are being installed, it's convenient to make a plywood jig to locate the holes at the proper center-to-center spacing, as well as the proper distance from the wall, as shown in figure 4-16.

After flooring is installed, the holes are covered by an escutcheon plate for a finished appearance, as seen in figure 4-17. Snap-on plastic sleeves are installed over the tubing to give a finished appearance and protect the tubing.

The variable-speed pressure-regulated circulator used for a homerun distribution system, should be set for constant differential pressure mode and operate 24/7 during the heating season. The speed of the circulator automatically adjusts as the thermostatic valve operators open, close or modulate flow through their associated radiators.

In an average residential system with perhaps 8-10 panel radiators, a variable-speed circulator with a low power input (under 50 watts at full speed) is often sufficient. The power input to the circulator is typically even lower under partial load conditions. The cost of operating the circulator in an area where electricity costs $0.20/kWh is often under 20 cents per day.

A Caleffi SEP4™ hydraulic separator decouples the pressure dynamics of the variable speed circulator from those of other circulators in the system. It also provides high performance air, dirt and magnetic particle separation.

See idronics 15 for more information on separation in hydronic systems.

When connecting the tubing to the radiators, be careful to observe the correct flow direction through the radiators. Flow should always be against the disc within the radiator's integral valve. Reversing the flow direction can create chatter and water hammer when the valve's disc is close to its seat.

Flow balancing of the homerun circuits can be done using the balancing features of the integral radiator valves. Many of these valves have an adjustable "shutter" that can be set to create a specific Cv. The higher the Cv setting of the integral valve, the lower the flow resistance through the radiator. Flow balancing can also be done using the balancing valves built into some manifold stations.

It's also possible to incorporate radiant panel heating circuits along with panel radiators, all supplied from the same manifold station. Since the manifold station supplies all circuits at the same, it's important to size the radiant panel circuits based on the supply temperature for the panel radiators or vice versa.

Another recommended detail is to use a manifold station with one or two extra ports beyond those needed for the initial installation. This allows for simple expansion of the system in the future. The unused ports should be capped until they are needed.

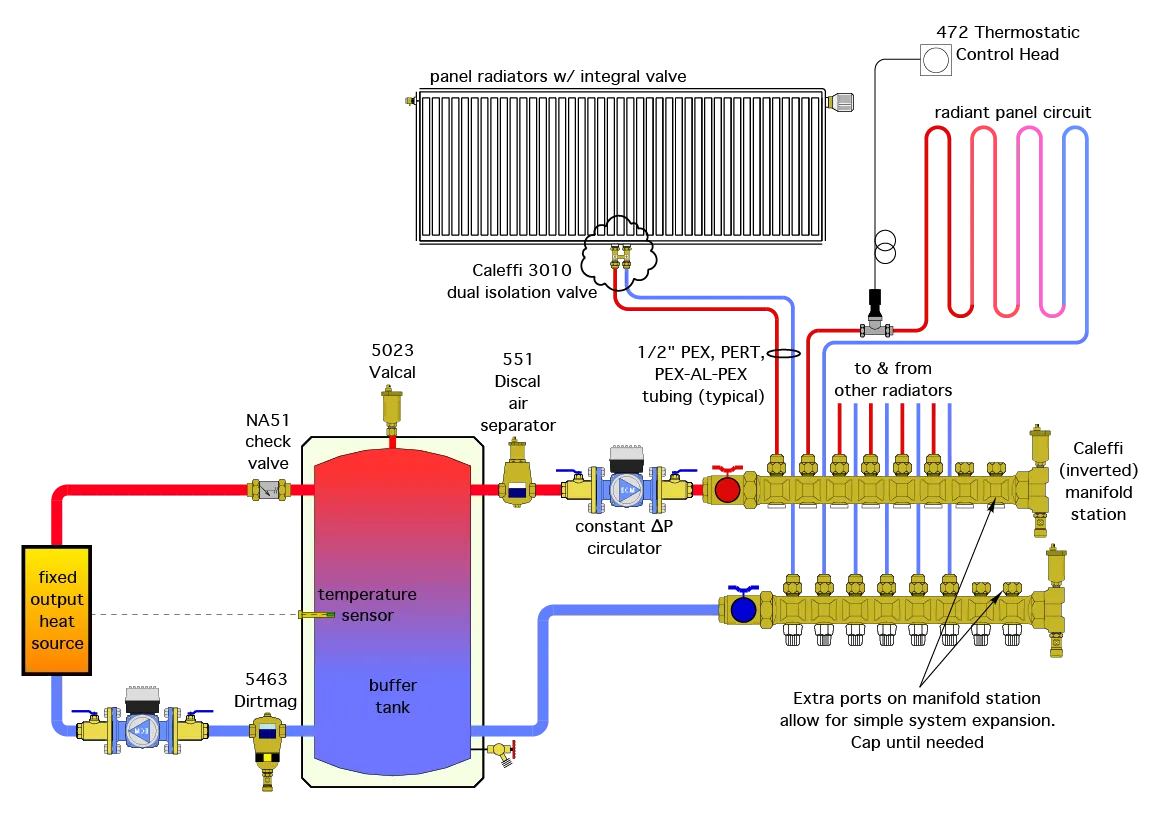

In systems where several panel radiators are supplied by a fixed output heat source, a buffer tank can be used in place of the SEP4 hydraulic separator. The thermal mass of the buffer tank protects the fixed- output heat source from short cycling when only one or perhaps two panel radiators are active. The buffer tank also provides hydraulic separation between the heat source circulator and the variable-speed pressure-regulated distribution circulator.

In the system shown the heat source monitors the temperature in the buffer tank and operates as necessary to maintain that temperature within a suitable range for the heat emitters. That range could be a setpoint combined with a differential. It could also be based on outdoor reset control. The latter usually improves the efficiency of the heat source. See idronics 17 for more information on buffer tanks.

The variable-speed pressure-regulated circulator operates 24/7. This system includes a Caleffi DISCAL® air separator and DIRTMAG® PRO dirt and magnetic particle separator. The latter ensures that the internal components in the heat source remain as clean as possible. It also helps protect the ECM circulators from magnetite accumulation.

The homerun distribution system serves both panel radiators and radiant panel circuits. The heat output of the panel radiators is regulated by thermostatic valve operators attached to the integral valves in the radiators. The output of the radiant panel circuit is also controlled by a thermostatic operator that combines the valve actuator with a wall-mounted adjustment dial, connected to the actuator by a capillary tube.

EXTENDED MANIFOLD SYSTEMS

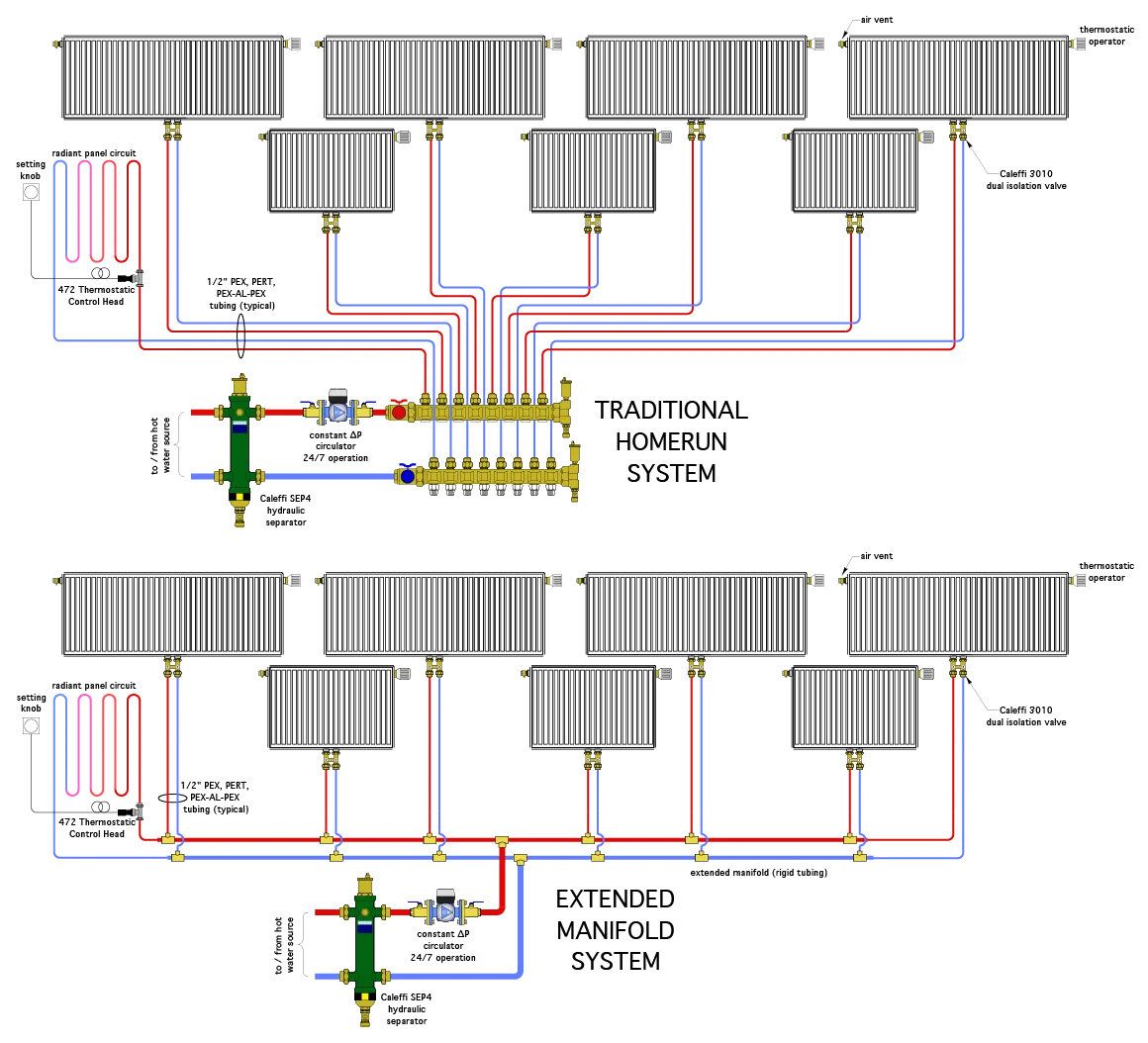

In some situations, the amount of tubing needed to facilitate "homerun" circuits from a single manifold station to each panel radiator, or other heat emitters, becomes inconvenient. Doing so could require many holes to be drilled through floor joists, which might have structural consequences. This approach might also require substantial amounts of tubing, which increases system volume and adds to heat loss if routed through partially heated spaces.

A variation on traditional homerun piping is the "extended manifold" piping configuration. It uses longer lengths of rigid tubing (typically copper), along with tees and transition fittings as a replacement for a central manifold station. This shows a traditional homerun distribution system and an equivalent extended manifold system.

The extended manifold approach is especially helpful in situations where the heat emitters are spread out over long distances within the building. It's also a good option when the extended manifold can be routed along a straight path, such as along the main girder supporting the center of the floor framing.

Both systems use a variable-speed pressure-regulated circulator that operates 24/7 during the heating season. The heat emitters can be any combination of panel radiators and radiant floor, wall or ceiling panels. However, all the heat emitters should be sized to operate at the same nominal supply water temperature.

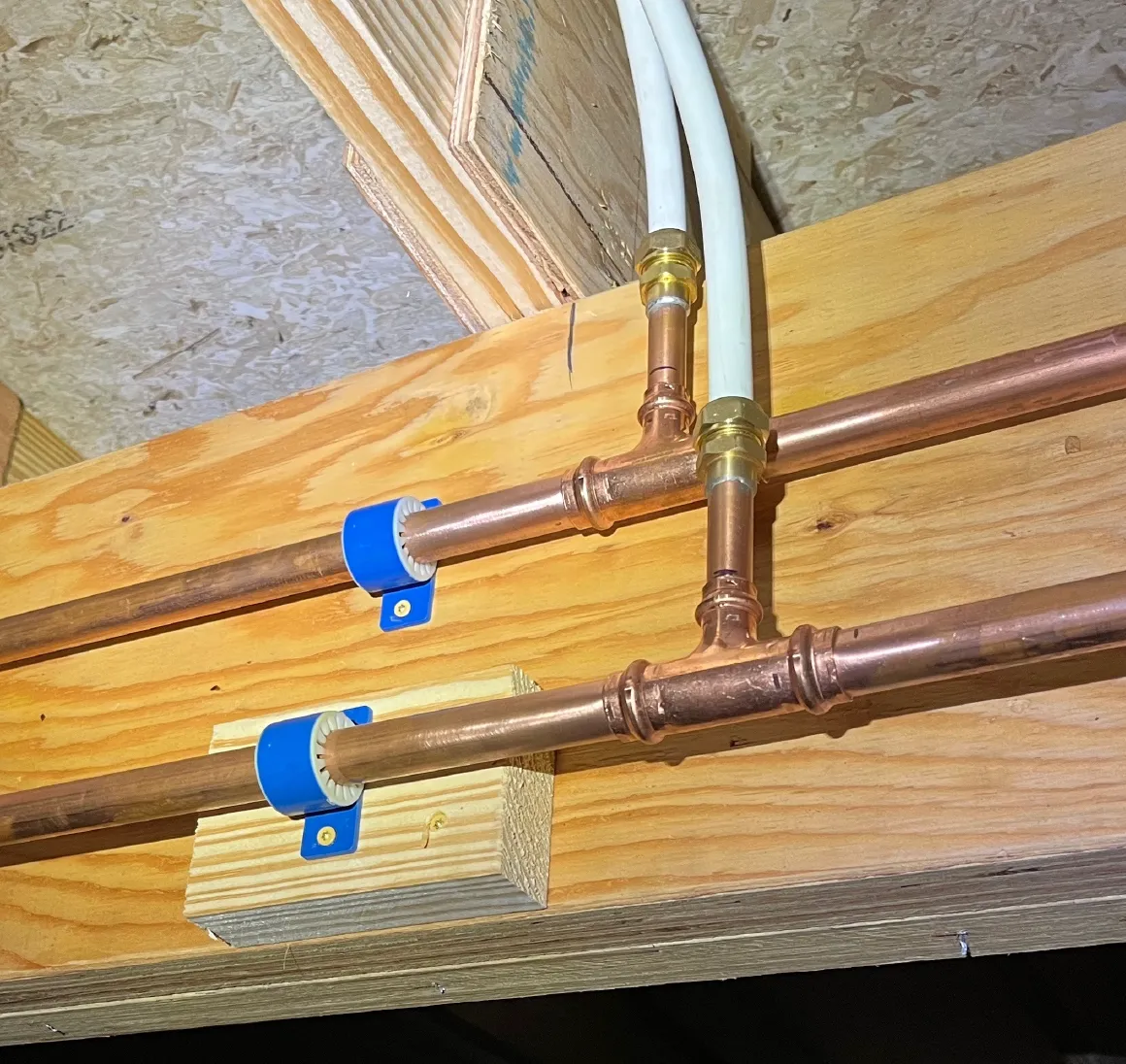

Figure 4-20 shows a "branching point" from an extended manifold made of 3/4" copper tubing routed along a girder that supports floor framing. The support clips allow tubing to expand and contract without developing stress or creating noise. The 3/4" x 3/4" x 1/2" reducer tees transition to connectors for $1/2^{\prime\prime}$ PEX-AL-PEX tubing, which leads to a panel radiator.

Figure 4-21 shows the end of the same extended manifold system where the 3/4" copper manifold transitions to three branches, each piped with 1/2" PEX-AL-PEX tubing. Two of those branches lead to panel radiators. The other branch leads to a floor heating circuit. Flow through the latter is controlled by a Caleffi 472 actuator attached to a Caleffi 221 radiator valve.

The piping configurations shown in figures 4-14 through 4-21 connect all the heat emitters in parallel. Each heat emitter has its own supply and return tube that originates at a manifold station or extended manifold. This approach allows each heat emitter to receive essentially the same supply water temperature.

Another approach that can significantly reduce tubing lengths is to connect two or three panel radiators into a "1-pipe" configuration using specially designed bypass valves that also provide for panel isolation.

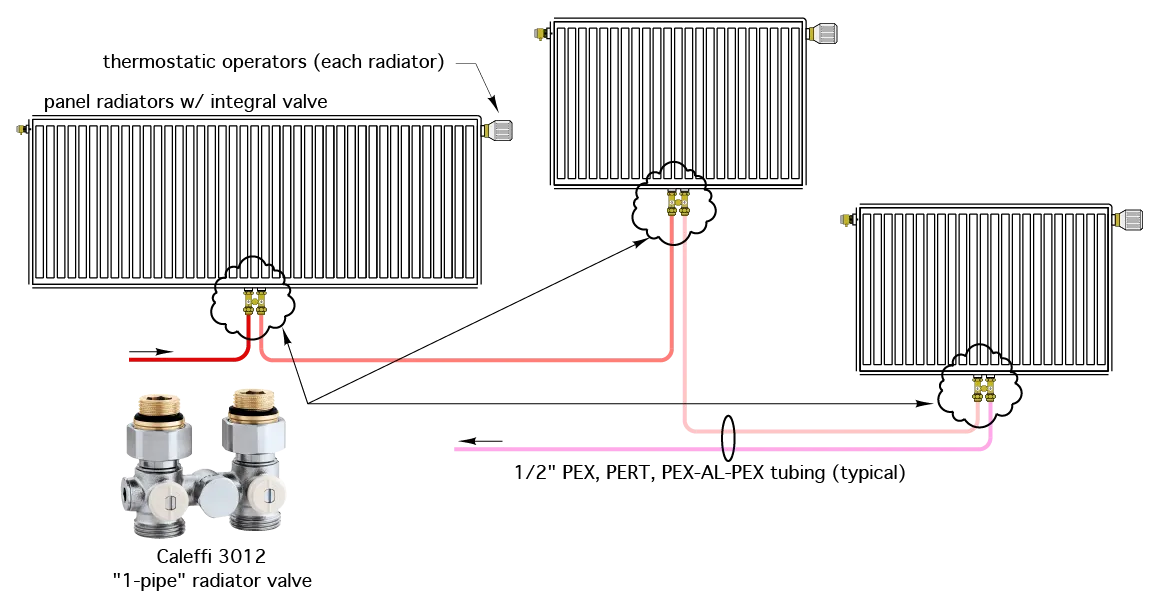

Figure 4-22 shows three panel radiators connected in a "1-pipe" configuration. Flow entering each Caleffi 3012 valve is divided. One portion passes through the radiator and the remainder passes through the horizontal bypass valve connecting the left and right sides of the valve body.

These valves also have a small side port for draining water from the radiator if it has to be removed from its mounting. The side drainage port can be opened with a 6mm Allen wrench.

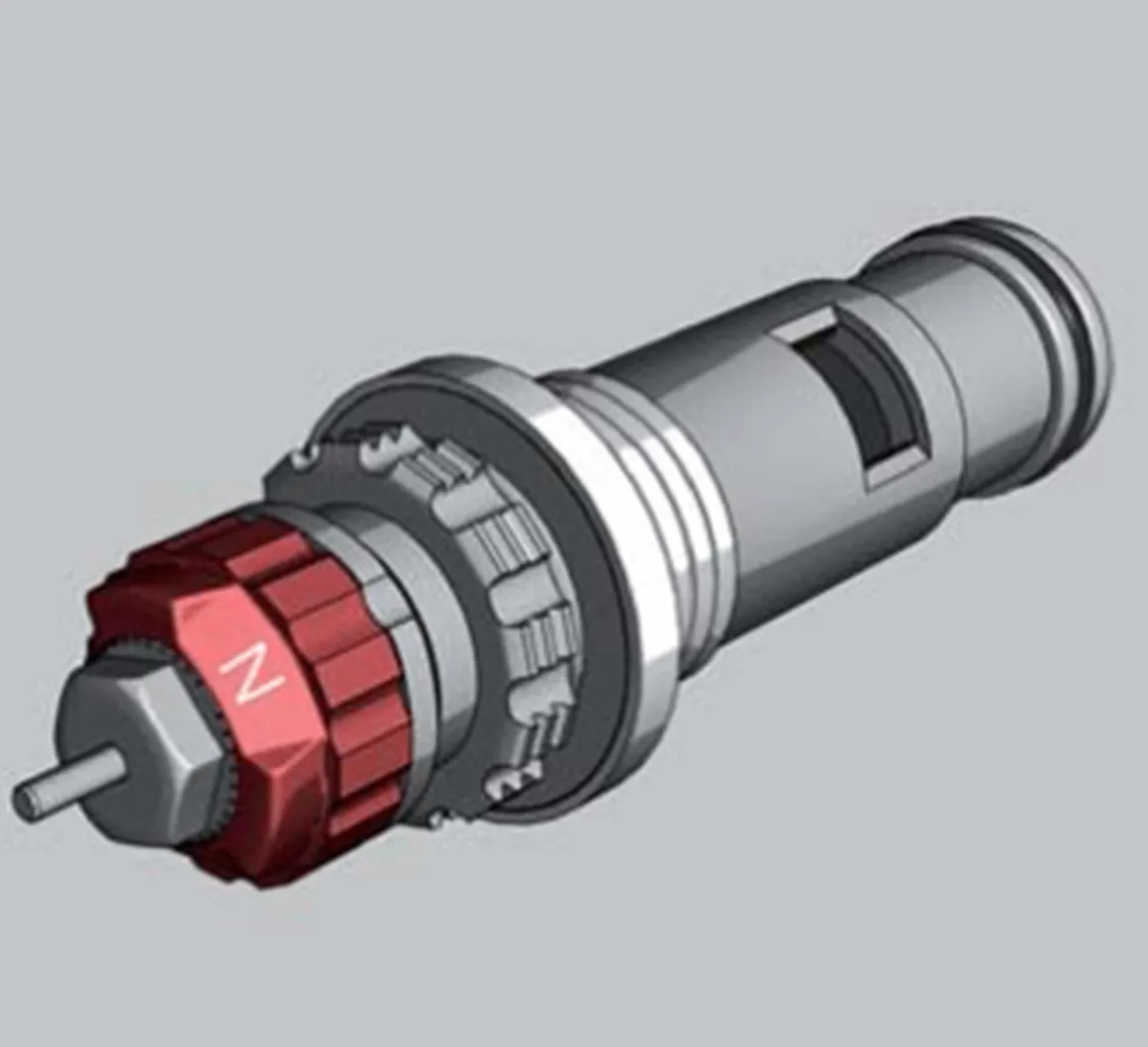

The Caleffi 3012 and 3013 valves are designed for use with "compact style" panel radiators. These radiators have bottom inlet and out connections spaced at 50mm (2") apart. Incoming flow enters the left side port and passes up through a tube inside the radiator that leads to the seat of an integral valve assembly. That valve assembly has a spring-loaded shaft. When the shaft is fully extended by the spring, the valve's disc is fully open. When the shaft is fully pushed in against the spring, the valve is closed. Figure 4-23 shows a typical integral valve assembly.

Figure 4-23 The integral valve assembly has a ring with numbers 1-7, and the letter N. These correspond to Cv values ranging — approximately linearly — from Cv = 0.15 at a setting of 1, to Cv = 0.7 at a setting of 7. The Cv at the “N” setting, where the shutter in the valve is fully open, is Cv = 0.83. The Cv of the valve can be set by turning the ring to align one of these numbers or the letter “N” with the groove on the valve body. In Figure 4-23, the letter “N” on the red ring is aligned with the grove on the valve body, meaning that the valve shutter, seen at the rear of the assembly, is fully open.

(Photo Courtesy of Purmo Group)

When a compact-style panel radiator with an integral valve is installed in a "1-pipe" arrangement, its supply and return connections are fitted with a "1-pipe" valve, such as the Caleffi 3012 and 3013 valves shown in figure 4-24.

These specialty valves combine three valves into a single assembly. The two outer valves are for isolating the radiator from the remainder of the system if it has to be serviced or removed. These two valves are meant to be fully open (normal operation) or fully closed (to isolate the radiator).

The center valve is a bypass valve. It can be adjusted by removing the cap and using a 6mm Allen wrench to turn the stem. The setting of this center bypass valve determines the hydraulic resistance between the inlet and outlet sides of the valve. The greater this resistance, the higher the percentage of entering flow that passes through the radiator.

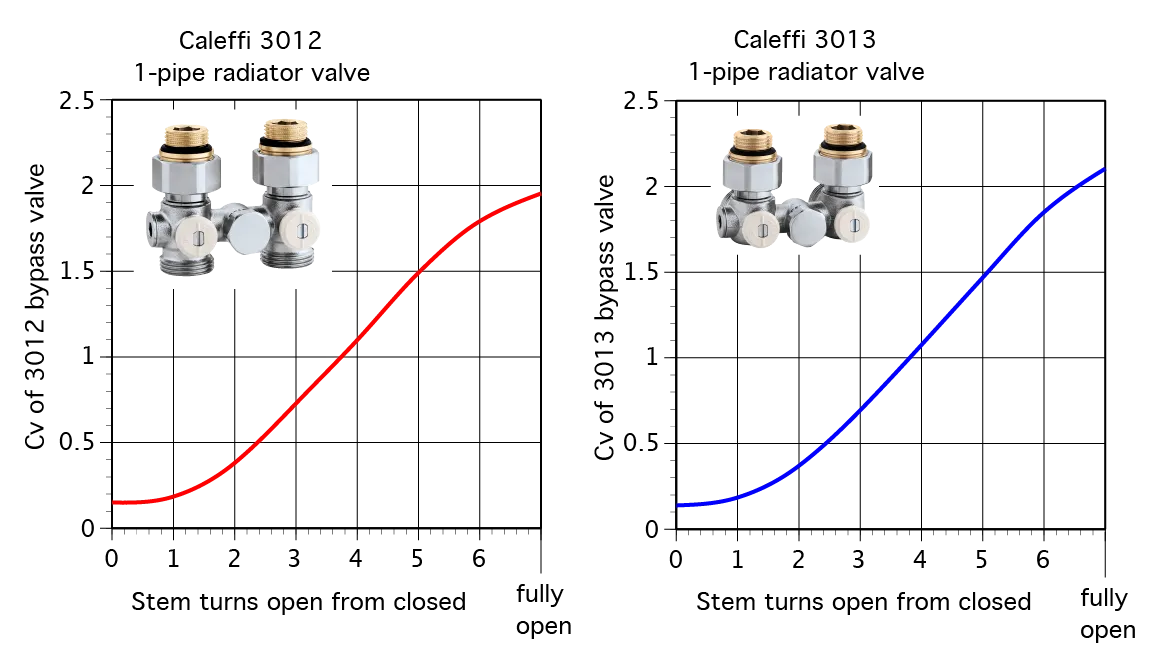

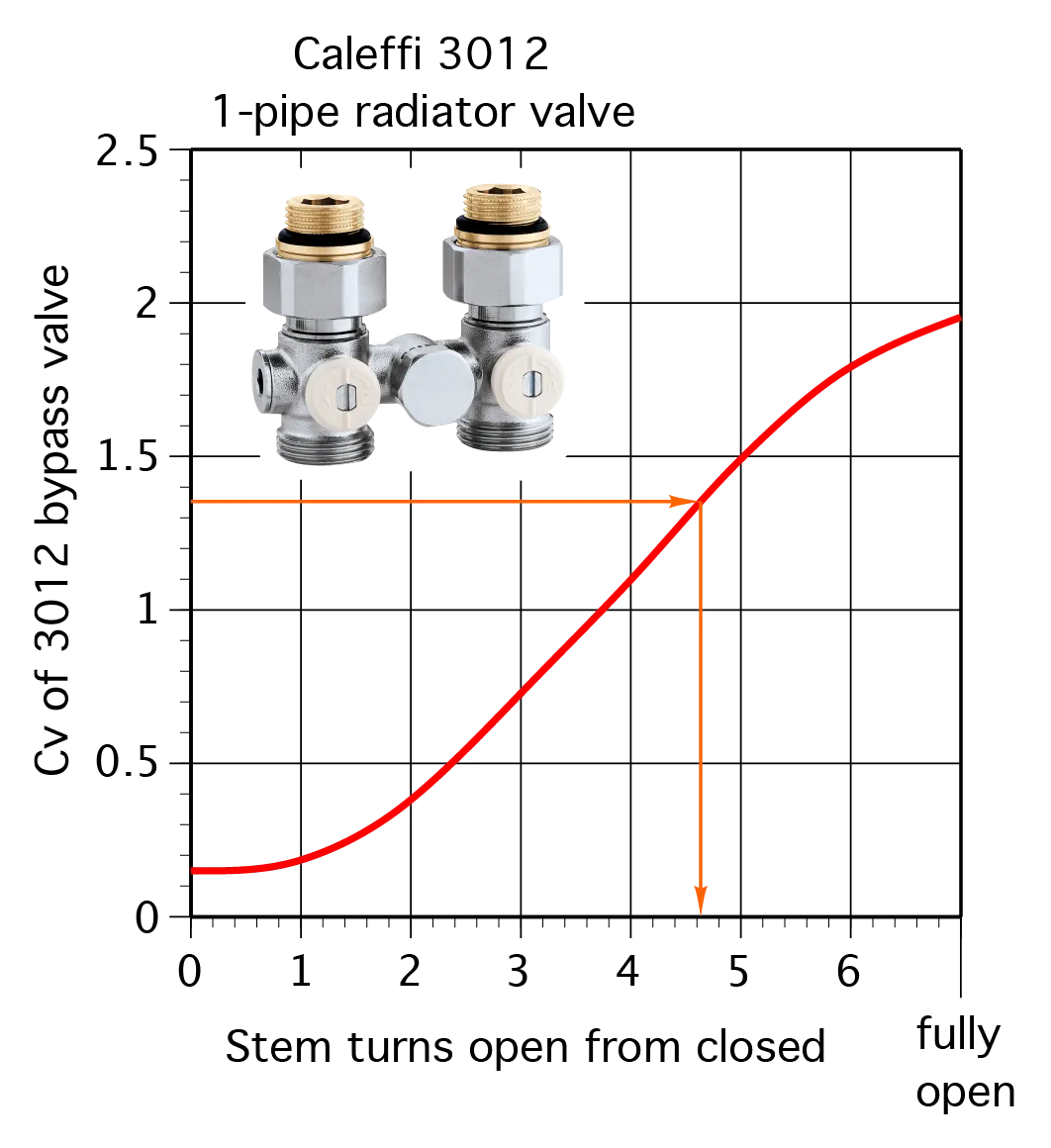

Figure 4-25 shows the Cv range of the center bypass valve in the Caleffi 3012 and 3013 1-pipe radiator valves.

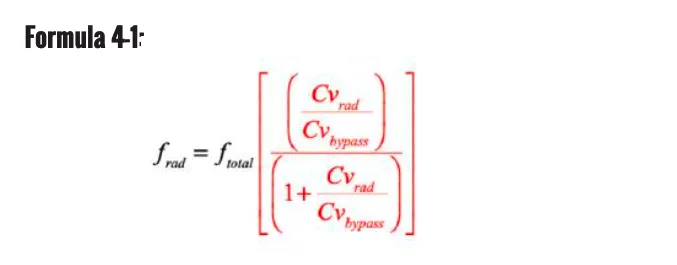

The flow passing through the panel radiator depends on the Cv of the radiator valve, as well as the Cv setting of the bypass valve. It can be calculated as a fraction of the flow entering the valve using formula 4-1:

Where:

frad = flow rate through the radiator (gpm)

ftotal = total flow entering the valve’s left side port (gpm)

Cvrad = Cv setting of the integral radiator valve

Cvbypass = Cv setting of the bypass valve

The value of the terms shown in red in formula 4-1 can be thought of as the decimal percentage of total flow entering the 1-pipe valve that passes through the radiator.

Formula 4-1:

frad = flow rate through the radiator (gpm)

ftotal = total flow entering the valve’s left side port (gpm)

Cvrad = Cv setting of the integral radiator valve

Cvbypass = Cv setting of the bypass valve

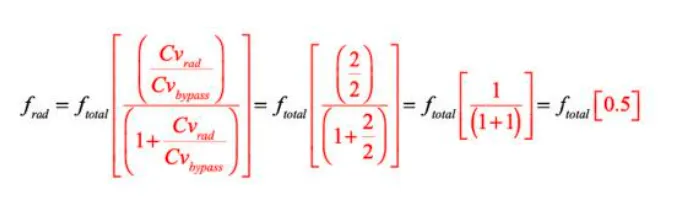

For example, if the Cv of the integral radiator valve is the same as that of the center bypass valve (2.0 for example), the red portion of Formula 4-1 becomes 0.5:

This implies that 50% of the flow rate entering the 1-pipe valve passes through the radiator, and the remaining 50% passes through the bypass valve.

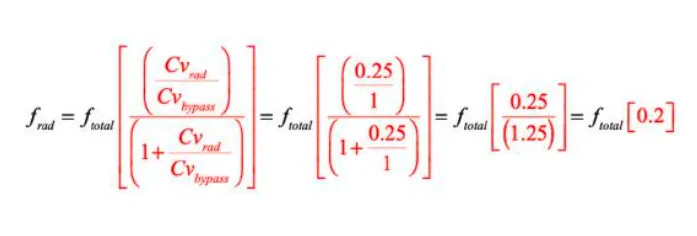

If the Cv of the radiator valve was 0.25, and the Cv of the bypass valve was 1, formula 4-1 would be as follows:

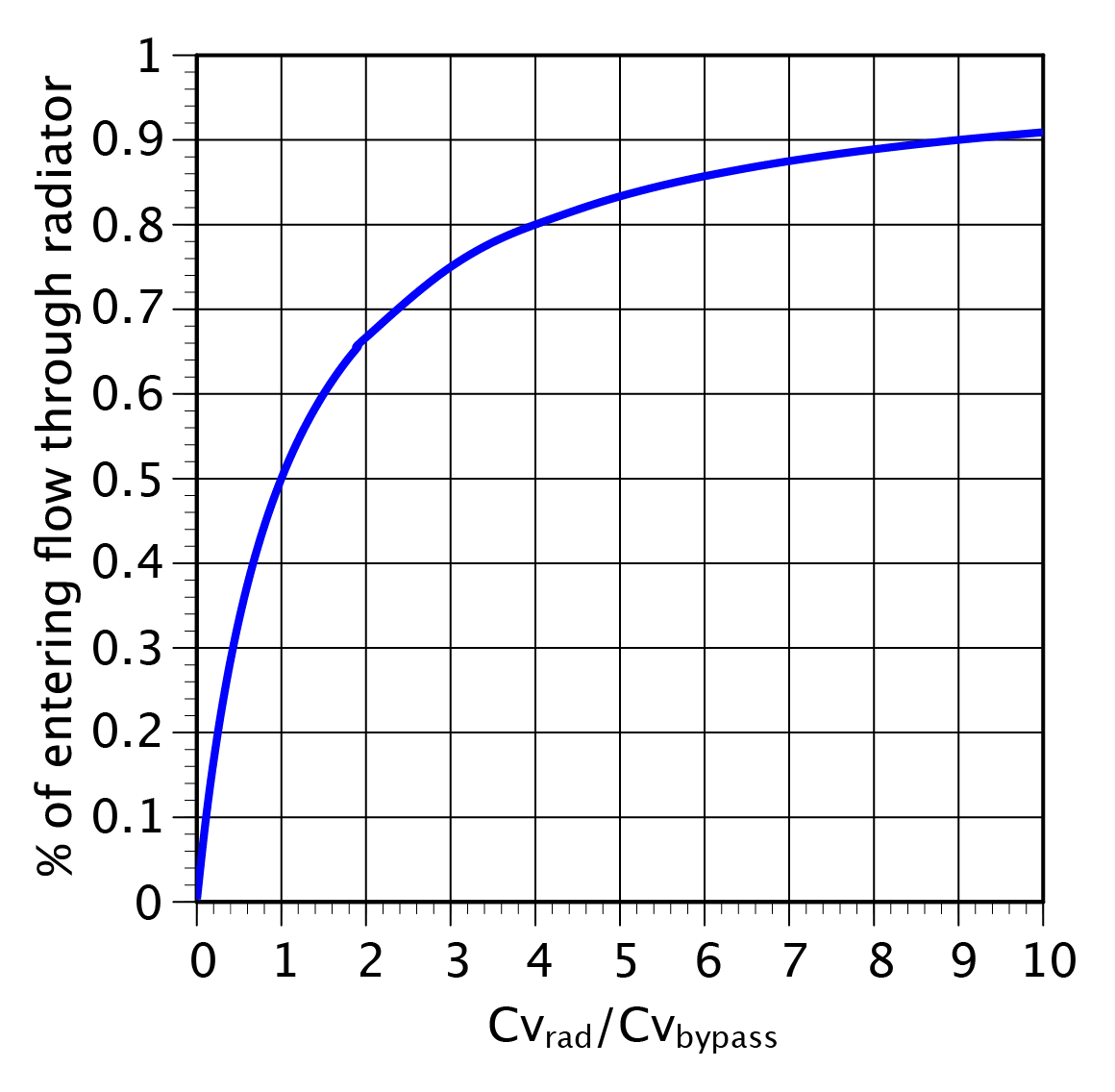

Figure 4-26 shows a plot of the percentage of entering flow that passes through the radiator as a function of the ratio (Cvrad/Cvbypass).

Caleffi 1-pipe radiator valves come preset so that approximately 35% of the flow entering the valve passes through the radiator, while the remaining 65% passes through the bypass valve. This default setting is usually acceptable when three identical panel radiators are piped as shown in figure 4-22. However, when radiators of different sizes are connected in a 1-pipe arrangement, the percentage of the total flow that passes through a given radiator should be approximately proportional to the design heat output of that radiator as a percentage of the total design heat output of all radiators in the 1-pipe circuit.

For example: Consider a 1-pipe circuit with two panel radiators. One radiator is sized for a design heat output of 5,000 Btu/hr and the other is sized for a design heat output of 8,000 Btu/hr. The total heat output of the string would be 5,000+8,000=13,000~Btu/hr The percentage of total flow through the 5,000~Btu/hr radiator would be 5,000/13,000 =0.38 or 38% of the total flow. The remaining 62% of total flow would pass through the other radiator.

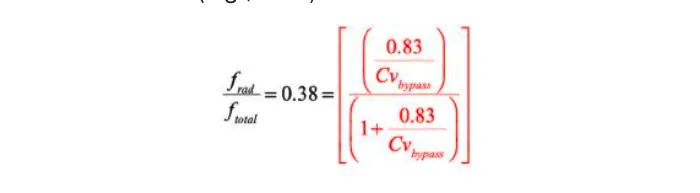

Assuming that the integral valve assembly in both radiators was set to “N”, the Cv of the integral radiator valves would be 0.83. To find the Cv setting of the bypass valve, set

up a slightly rearranged form of formula 4-1, knowing that the fraction of entering flow that needs to pass through the radiator is 0.38 (e.g., 38%) of the circuit flow.

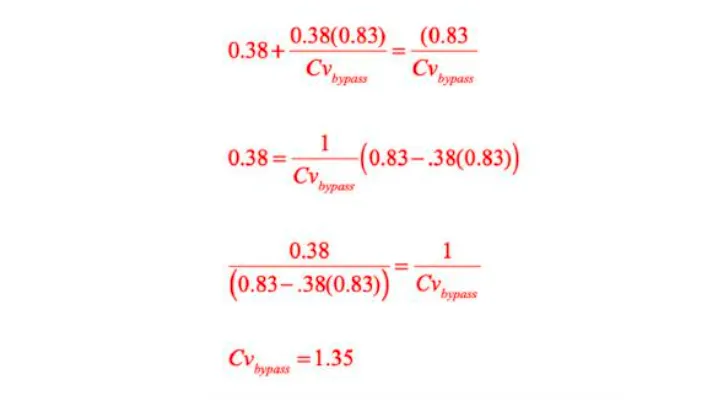

This rearranged form of formula 4-1 can be solved to get the value of Cvbypass:

Referencing figure 4-25 shows that opening the plug of the Caleffi 3012 bypass valve 4.6 turns would yield a Cv of 1.35 for the bypass valve, as shown in figure 4-27.

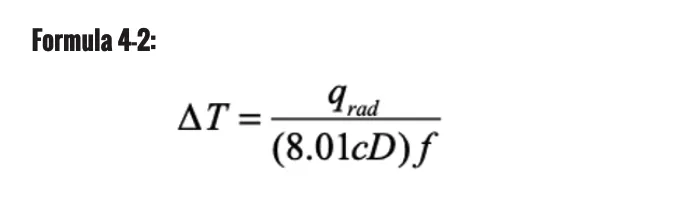

The temperature drop of the flow stream passing through a 1-pipe radiator valve can be calculated using formula 4-2:

Where:

∆T = temperature drop of fluid from inlet to outlet of dual isolation valve (ºF)

qrad = heat output of radiator (Btu/hr)

8.01 = a constant need for units

c = specific heat of fluid (Btu/lb/ºF)

D = density of fluid (lb/ft3)

f = circuit flow rate (gpm)

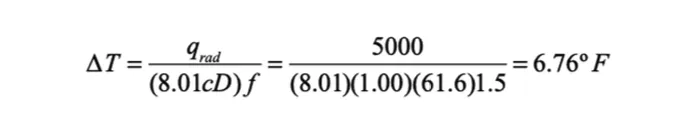

For example: Assume that a panel radiator releases 5,000 Btu/hr when supplied with 120°F water and operating in a room with a 70°F air temperature. Also assume that flow rate in the 1-pipe circuit is 1.5 gpm. Determine the outlet temperature from the 1-pipe valve.

Solution: The density of water at 120°F is 61.6 lb/ft. The specific heat of water at $120^{\circ}F$ is $1.00~Btu/lb/^{\circ}F$ Putting these fluid properties and the given values into formula 4-2 yields the temperature drop across the radiator.

The outlet temperature from the dual isolation valve which typically is assumed to be the inlet temperature for the next radiator in the 1-pipe circuit is 120 - 6.76 = 113.2°F.

Note that it is not necessary to know how the circuit flow entering the 1-pipe valve divides between the radiator and the bypass valve to make this calculation. The flow passing through the bypass valve would mix with the water leaving the panel radiator to produce a "net" temperature drop of 6.76°F.

In a 1-pipe configuration, each active radiator, other than the first one on the supply side of the circuit, receives water at a temperature lower than the radiator upstream of it. Because of this sequential temperature drop, the radiator "string" should be limited to three radiators, and the maximum design load output for the string should be limited to about 34,000 Btu/hr (10 kW), assuming a high supply water temperature to the first radiator in the range of 180 to 190°F. When lower supply water temperatures are used, it's prudent to limit the string to two radiators.

The thermostatic radiator valves (such as shown in figure 4-7), and thermostatic operators fitted to radiators with integral valves (shown in figure 4-11), both regulate flow based on the air temperature near the heat emitter. It's also possible to use non-electric thermostatic operators to regulate flow based on other temperatures in the system.

Figure 4-28 shows a radiator valve body, such as a Caleffi 221 or 220 valve, fitted with a Caleffi 472 thermostatic actuator assembly.

This assembly allows the space comfort level to be set using a dial located on a wall, typically about five feet above the floor, as shown in figure 4-29. This assembly is ideal for situations where occupants may not have the willingness or the mobility to reach thermostatic operators located on low-profile radiators near the floor.

When using this assembly, it's important to remember that it's a capillary tube not a wire connecting the valve actuator to the setting dial. The capillary tube cannot be cut or extended. It needs to be routed from the setting dial location to the valve. Any holes needed for this routing need to be large enough for the actuator head to pass through (e.g., the black cylindrical part of the assembly seen screwed to the valve in figure 4-28).

It's also important to mount the valve body in an accessible location. If mounted within a wall or ceiling cavity that will eventually be covered with drywall or other materials, an access panel should be provided.

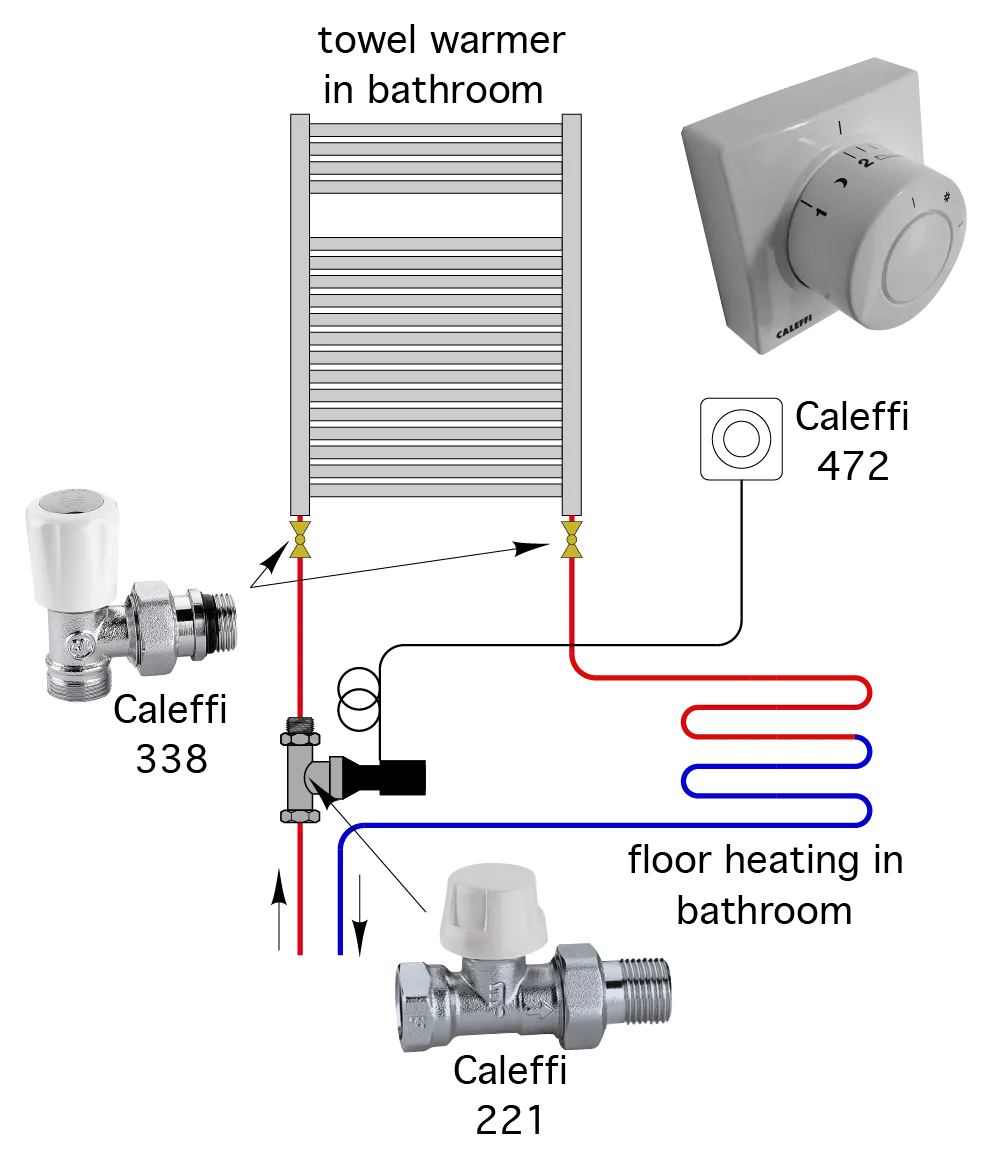

Figure 4-30 shows an application that uses a thermostatic valve to regulate flow in a circuit that supplies a towel warmer and floor heating in the same bathroom.

The comfort level in the bathroom is set using the wall- mounted dial of the Caleffi 472 actuator assembly, which controls flow through the Caleffi 221 radiator valve. The capillary tube connecting the dial and actuator is routed through the wall cavity. A pair of Caleffi 338 angle valves make the transition between the 1/2" PEX tubing and the ports on the towel warmer radiator. These valves allow the radiator to be isolated from the circuit if ever necessary.

Two or more Caleffi 472 actuator assemblies could also be used for controlling flow in independent zone circuits. However, the capillary tube length is limited to 78 inches, which means that the valve bodies need to be relatively close to the location of the setting dial..

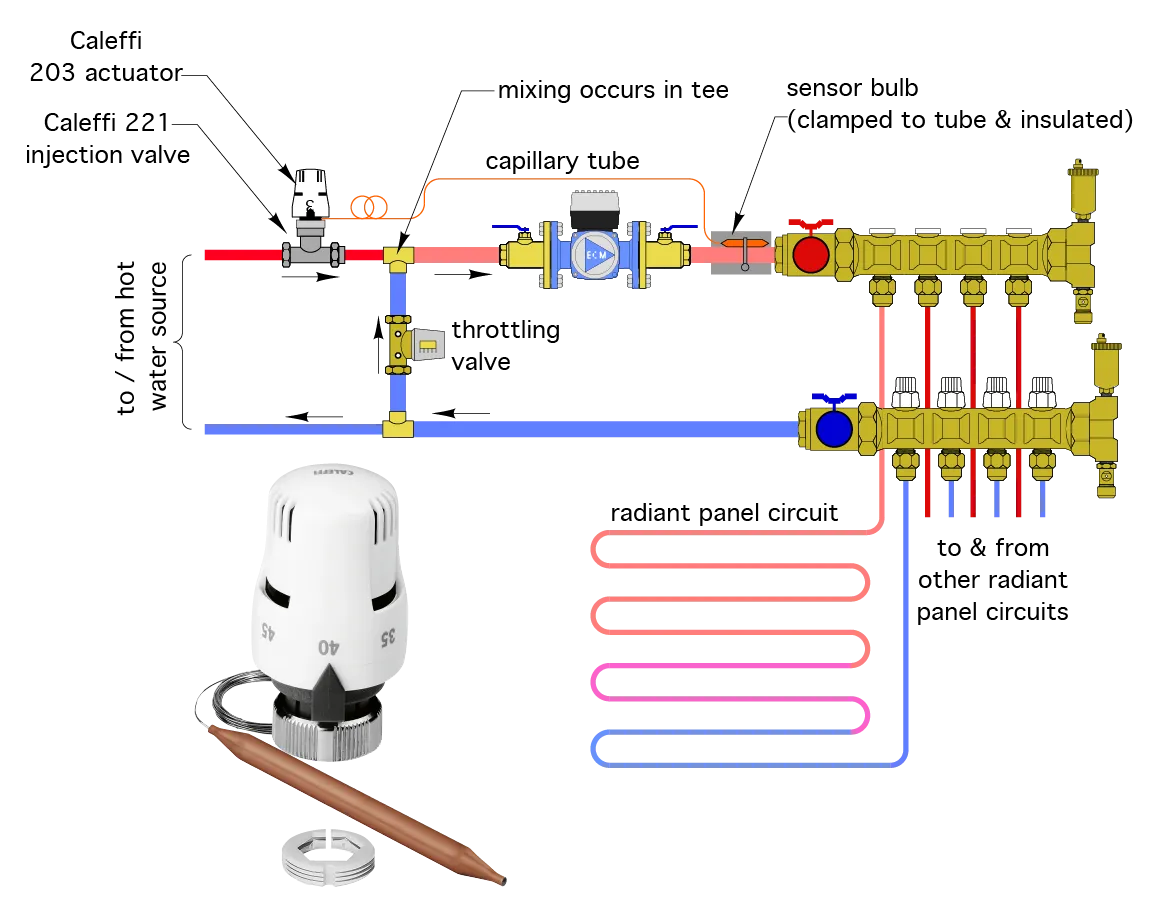

Another application for non-electric thermostatic control is a situation where flow rate needs to be controlled based on the temperature of a pipe surface, or a sensor mounted in a sensor well. This can be done using a Caleffi 203 actuator assembly combined with a Caleffi 220 or 221 radiator valve.

One example of such an application is maintaining a setpoint temperature to the radiant panel circuits using injection mixing, as shown in figure 4-31.

A portion of the cool water returning from the radiant panel circuits passes through the throttling valve and mixes with hotter water that has passed through the injection valve. The mix proportions determine the supply temperature to the manifold station. The amount of water passing through the injection valve depends on the setting of the 203 actuator and the temperature at the sensing bulb. If the sensed temperature is lower than the dial setting, the valve opens more, and vice versa. The numbers on the knob of the 203 actuator assembly are setpoint temperatures in °C.

The knob for the 203 actuator assembly mounts to the injection valve. A capillary tube connects this assembly to a sensing bulb that's clamped to the pipe supplying the manifold station. The Caleffi 203 actuator assembly has a 78-inch-long capillary tube connecting the actuator with the sensing bulb. This capillary tube cannot be cut. Any access length of capillary tube should be neatly coiled near the valve.

The throttling valve in figure 4-30 creates the differential pressure necessary to drive hot water through the injection valve as it opens. As the pressure drop through the throttling valve increases, the induced hot water flow rate through the injection valve also increases.

The throttling valve should be adjusted when the injection valve is fully open. Start with the throttling valve fully open, thus creating its minimum pressure drop. Slowly close the throttling valve while measuring the mixed supply temperature. The goal is to create a mixed supply water temperature that allows the radiant panel circuits to meet design load output when the injection valve is fully open.